Students from St. Joseph High School in Brooklyn, New York, smile as they participate in the Global Climate Strike in New York City Sept. 20, 2019. James Holzhauer-Chuckas, a youth minister in Evanston, Illinois, said many young Catholics are very concerned about climate change and want to know what the church is doing to combat it. (CNS/Gregory A. Shemitz)

James Holzhauer-Chuckas is the senior director of the United Catholic Youth Ministries at four parishes in Evanston, Illinois, and a Benedictine oblate who once thought of becoming a priest. He's a proud Catholic — the last one "standing" in his family, he told NCR, after his parents and siblings left the church amid the clergy sex abuse crisis and disagreements with the church's stance on LGBTQ rights.

He's also a bit of a statistical anomaly — a child of unaffiliated parents who identifies as Catholic. Among today's teenagers, the trend usually goes in the other direction, according to new research.

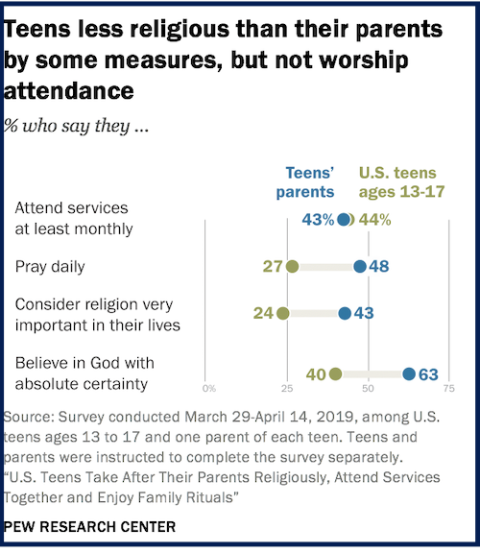

A Pew Research Center study released Sept. 10 suggests that most American teens share religious identities and faith practices with their parents, but that teenagers are much less likely than their parents to say religion is very important to them.

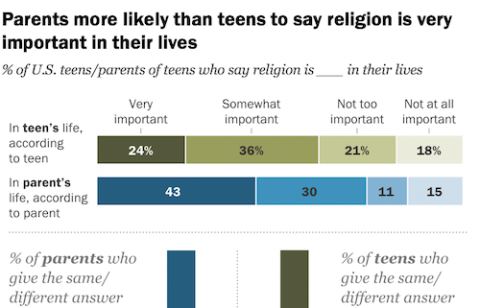

For instance, nearly half of all teens say they hold all the same religious beliefs as their parents, and most have gone to religious services with at least one parent. But while 43% of parents said religion is "very important" to them, just 24% of teens said the same.

"A lot of what this survey shows is that teens are fairly religious and they take after their parents. They're also less religious on some measures," said Pew senior researcher Elizabeth Podrebarac Sciupac, who co-authored the study. "It's kind of this-and-that, at the same time."

In the study, researchers surveyed 1,811 pairs of U.S. subjects: one teenager aged 13 to 17 and one parent or guardian from the same household. Sciupac said the team wanted to learn more about the future of religion in the U.S.

"Part of the impetus here was to measure, especially with the changing religious landscape in the United States [and] how it has become more unaffiliated within the past 10, 15 years or so — what are we seeing with teens?" Sciupac told NCR. "What are we seeing in terms of their affiliation, their beliefs, their practices — and how does that fit into the broader narrative?"

Researchers found that most U.S. teens identify with a religion. About six in 10 are Christian, and 24% are Catholic, according to the survey. Latino teens are more likely to identify as Catholic — 47% — than their white peers, only 17% of whom identified as Catholic. Catholic teens are more concentrated in the West and Northeast regions of the U.S. as opposed to the South or Midwest.

Advertisement

Teens are more likely than their parents to identify as "nones" or unaffiliated, researchers found. Thirty-two percent of teens did not identify with a religious faith, compared with 24% of parents. And about one fourth of unaffiliated teens had a Catholic parent.

Holzhauer-Chuckas said many parents he works with in family ministry are worried their kids will leave the church. The church's hardline stance against LGBTQ rights alienates a lot of teenagers, he said, as it did with his two moms and his siblings. Many young people also express frustration that the church won't ordain women, and they are hurt by the church's response to the sexual abuse crisis.

"Young people don't see a lot of positive messages about the church in [the] media," he said. "And I think parents fear that if that's the only thing they're seeing and they're not already participating in the parish or in a youth ministry, it's easy for them to walk away."

He said since he's been working in youth ministry, religious education in Catholic spaces has taken a dogmatic turn that doesn't appeal to young people's desire to actively live their faith.

"It was much more about … 'you're being confirmed if you can name the seven gifts of the Holy Spirit,' rather than, 'how am I going to live out my confirmation?' " he said.

Teens are much less "dogmatic" than parents, according to Pew's findings, and they have a lot of questions about God's existence, the role of evil in the world and whether or not any one religion is the only true faith. While 63% of parents said they were absolutely sure of God's existence, just 40% of teens said the same. Catholic (and mainline Protestant) teens showed even less certainty in God's existence and the absolute truth of one sole faith than evangelical teens.

Just under half of Catholic and mainline Protestant teenagers said they were certain of God's existence, compared with about seven in 10 evangelicals. Only about three in 10 Catholic and mainline Protestant teens said they thought there was truth only in one religion, while two thirds of evangelical teenagers said the same.

Catherine Lucy, a Catholic parent of three teenagers in St. Louis, said her kids will sometimes bring up questions about political or faith-related issues, such as abortion and what happens after people die. She said she does her best to teach them the Catholic Church's stance, while also giving them information about opposing arguments.

"Not that they would, but I don't want them to think they're being brainwashed and that I'm only going to teach them one thing," she told NCR. "I want them to know both sides of an issue."

Chart showing percentage of teens who attend religious services, pray daily, believe in God with absolute certainty (Pew Research Center)

Instead of belaboring doctrinal issues, Holzhauer-Chuckas said he tries to engage teenagers in practical activities, such as service work or participating in the liturgy. Prior to COVID-19, his churches held youth Masses where young people lectored and read announcements. This inspired other parents and teenagers to get involved as well.

"When you're a teenager, you're questioning everything, and I think they occasionally get annoyed with, 'Why do I have to do this every week?' " Lucy said. "But I think that's just part of being a teenager, and I never come down hard on them … like, 'You have to do this because I say so.' "

Most teens' families engage in some form of religious practices or discussion at home, according to Pew. Roughly six in 10 teens reported talking about religion, about half said they prayed before eating, and one fourth read the Scriptures, although Catholics did so at lower rates than Christians overall. About half of Catholic teens said they enjoyed doing these things at least somewhat.

Holzhauer-Chuckas said teenagers are often curious about faith. Despite what they may say, they also care about what their parents think.

"I think young people are a lot smarter than we give them credit for, and they're very spiritual," he said. "And I think if we give them the tools, and with the parents' guidance, and their own faith, I think they have everything they need to start … to see with their own eyes."

Despite the efforts of people like Holzhauer-Chuckas, teenagers aged 13 to 17 do seem to be less enthusiastic about religion than their parents. Compared to their parents, teens are less likely to view religion as "very important" to their lives. About one-fourth of Catholic and mainline Protestant teens said religion was very important to them, as compared to about half of evangelical teens.

Lucy said her children have different expectations of what a Catholic life might look like than what she was raised with. They may not prioritize early marriage to another Catholic, or putting their children through Catholic school, the way some in older generations did. She said she knows her kids may grow to have differing opinions on religion, but she doesn't want it to be a roadblock in their relationship.

Students from St. Alphonsus/St. Patrick Catholic School in Lemont, Illinios, pray Oct. 19, 2019, during Holy Fire Chicago at the Credit Union 1 Arena. A new Pew Research Center study suggests most U.S. teens aged 13-17 identify with a religious faith and participate in faith-related activities with their families. (CNS/Chicago Catholic/Karen Callaway)

"I feel like whatever choice they make as an adult, I can support them, because I know they had a good foundation and I know they're going to think things through and make the decisions that are best for them," Lucy said. "I feel like there's no point in feeling disappointed or saying I wish things had come out differently, because I want to have a good relationship with my children."

Finally, researchers wanted to find out how well parents and teens knew each other when it came to religion, Sciupac said. They asked both the teen and the parent to rate how important religion was in their life, and then to rate how important they thought religion was to the other.

In about seven in 10 cases, parents and teens accurately assessed how important religion was to the other. When they missed, parents generally thought religion was more important to their teen than it actually was.

But in four in 10 cases, both the teen and the parent said the two shared all their religious beliefs. Sciupac saw all this as a sign that parents and teenagers, on average, know each other pretty well when it comes to religion.

"I think that that is particularly interesting when you see so much about teens and parents not being on the same page religiously … this is a way in which they're experiencing religion together," she said.

Holzhauer-Chuckas said he tries to encourage parents and teens to talk to each other about their religious beliefs and try to understand one another better. Sometimes, it works.

"After a pancake breakfast … a kid said to me, 'I see my dad differently.' And for me, it was just so powerful that I had tears," he said. "Because I'm like 'What do you mean you see your dad differently?' And this kid said to me, 'I don't know. I never thought in my faith, I could feel this close with my dad.' "

[Madeleine Davison is an NCR Bertelsen intern. Her email address is mdavison@ncronline.org.]