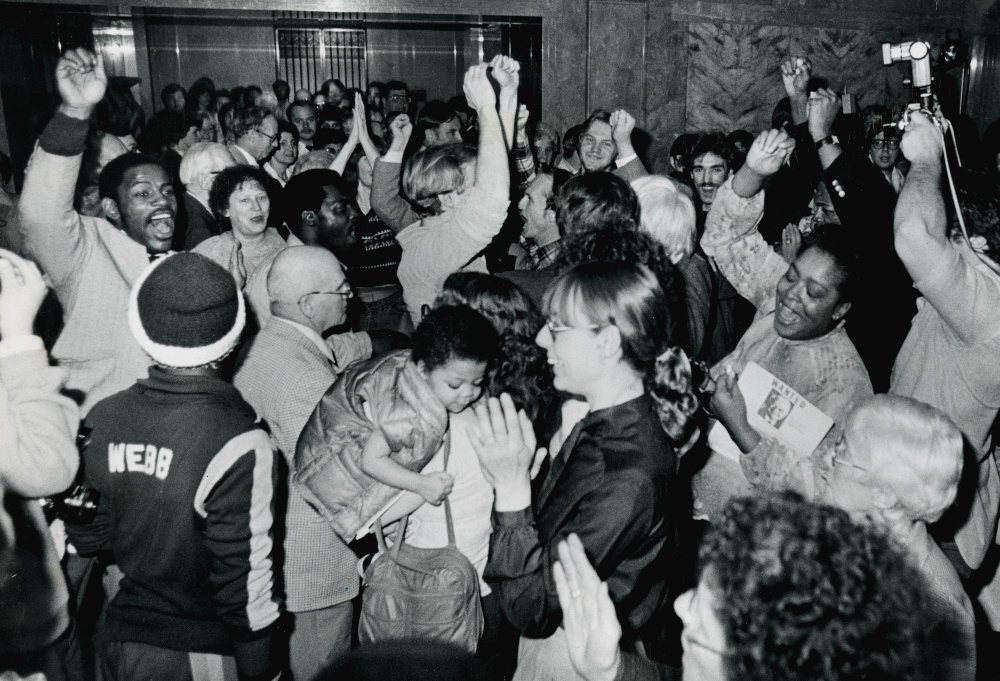

At the Joslyn Art Museum in Omaha, Nebraska, on April 14, 1982, members of Iowa Citizens for Community Improvement hear the news that InterNorth Inc. Board President Willis Strauss agrees to a meeting. (Courtesy of Omaha World Herald)

On April 13, 1982, two buses full of multiracial, everyday Iowans pulled up to the Joslyn Art Museum in Omaha, Nebraska. Posing as tourists, they walked into the museum, paid for their tickets and spread out, quietly looking at exhibits in small groups.

An hour later, they slowly made their way toward the auditorium, where InterNorth Inc. stockholders waited to enter their annual meeting.

The group of Iowans, dressed down in jeans and spring jackets, converged around Geneva Wredt, a 53-year-old woman from Council Bluffs, who led them to a side door. Shouting they had had enough of high utility rates, men flanking Wredt grabbed the door but were blocked by security. A wrestling match ensued as a former Catholic priest turned community organizer named Joe Fagan played tug of war with the door and the guards.

The crowd chanted, "It's been cold in our house; we want Strauss," and testified they had come from places like Waterloo and Cedar Rapids to demand Board President Willis Strauss invest in fuel assistance and home weatherization grants for poor people.

The spectacle drew the attention of the entire museum. Event coordinators stopped checking IDs and quickly ushered the shareholders through the main doors into the auditorium. Among them was Des Moines resident Norma Kain, who was dressed up to look the part but did not own shares in the utility company. Neither did dozens of other formally dressed people, secretly from the same group of Iowans.

Twenty minutes went by as Strauss waited to make sure Omaha police had arrived and the group of rabble-rousers were isolated outside. Inside, shareholders joked about freezing babies, which made Kain's skin burn with anger.

Finally, Strauss walked to the stage and addressed the crowd. Kain stood up, pulled a whistle from her neck and blew it. She demanded InterNorth pass the Iowa Citizens for Community Improvement resolution to create a $10 million grant and loan pool for low-income neighborhoods.

Guards escorted her out, but another person stood up, blew a whistle and shouted the same demand. After several more rolling disruptions, Strauss adjourned and agreed to meet with Iowa CCI.

Advertisement

Iowa CCI kept up the pressure, and within three years, InterNorth created a $1.5 million fund, canceled one of its Omaha shareholders meetings, moved to Houston and renamed the company Enron.

Grassroots leaders from the impacted communities were the public face of the fight, but behind the scenes, Fagan and his small staff facilitated months of one-on-one conversations, planning meetings and "hits" to win the campaign.

"Direct action is what we do when the target says no," Joe often said.

By the time Fagan died Sept. 2 at age 80, the CCI organization he founded in 1975 and directed until 2003 had its own building, 5,000 members, hundreds of experienced leaders, 19.5 full-time staff, a political action committee and a 45-year legacy of building power.

Over the years, Fagan took CCI from its humble beginnings as a neighborhood group working on broken curbs and vacant buildings to a statewide force to be reckoned with. CCI became a pejorative among landlords, developers, bankers and politicians across the state.

Under Fagan's direction, CCI grew across Iowa, uniting rural and urban people from all walks of life and impacting both federal legislation and presidential politics.

In 1976, Iowa CCI helped draw national attention to redlining in Waterloo and Des Moines. It was a notable part of the People's Action coalition that won the 1977 Community Reinvestment Act.

In 1990, after years of Farm Crisis organizing, CCI was the first group in the country to use the Community Reinvestment Act to negotiate nearly $37 million in credit for 1,200 small and midsized farms. CCI is synonymous in rural Iowa with grassroots resistance to factory farms and has spearheaded decades of policy changes at the state legislature.

Iowa CCI was among the first groups in the country to endorse Bernie Sanders for president, support Occupy Wall Street and organize civil disobedience against the Dakota Access pipeline. It continues to fight for racial justice and community control of the police today.

"Eleven former employees of a Des Moines laundry service who complained of poor working conditions and bounced checks have obtained nearly $9,200 in back wages, Iowa Citizens for Community Improvement announced this week," read the March 31, 2010, lede in the Des Moines Register. (Courtesy of Iowa CCI)

In 2011 at the Iowa State Fair, a year after he had already retired, Fagan goaded GOP presidential candidate Mitt Romney into the stump speech gaffe "Corporations are people, my friend."

"When I first met Joe, I thought he was one of the Berrigan brothers," said Paul Battle, a CCI organizer in Waterloo in 1977.

Joseph Placid Fagan was born on March 14, 1940, on a farm outside of Dubuque, just 3 miles east of New Melleray Abbey, a Trappist monastery. He was baptized by the abbey's priest, Father Placid.

Joe's father, Francis, lived through the Great Depression and was a strong supporter of the National Farmers Organization.

"Dad believed in gathering folks together to work on the issues," said Joe's sister Ruth Fagan, a member of the Sisters of St. Francis. "When my parents went to visit somewhere, they stopped and met with everybody along the way."

A formative experience came in 1950 when Joe saw "The Jackie Robinson Story" for the first time. He was outraged at the racial discrimination the movie depicted.

"I could never imagine anything more unfair in my life," he said.

Fagan grew up helping his dad on the farm, but he still had plenty of time for baseball, which he played through his time at Loras College. He was ordained a priest on June 3, 1967. Coming of age after the 1962-65 Second Vatican Council, Fagan interpreted the Gospel as an option for the poor.

"Joe was progressive in his thinking and always wanted to make his liturgy relevant, so he started a liturgy committee, and together we would plan the Sunday liturgy," said Lou Ann Burkle, a nun on the parish staff whom Fagan fell in love with and married. They left their vocations in 1979.

The founding priests of Iowa Citizens for Community Improvement pose for a photo at the group's 30th anniversary convention in 2005. From left: former priest Vince Hatt, Fr. Gene Kutsch, former priest Joe Fagan, and Fr. Tom Rhomberg. (Courtesy of Iowa CCI)

Fagan's mentor, Fr. Gene Kutsch, had first heard about community organizing in 1974 at a Catholic Committee on Urban Ministry convention in Indianapolis, during a workshop by Jesuit Fr. John Baumann of Oakland, California. Before long, a committee of priests raised enough money to send Fagan to Chicago for community organizer training with Shel Trapp and National People's Action.

After a summer in the trenches, Fagan returned to Waterloo and started knocking on doors.

"What are people mad about?" Joe always wanted to know.

For 30 years, CCI was funded by the U.S. bishops' Catholic Campaign for Human Development. But Fagan insisted on building a broad-based organization independent of any one source of support. This proved prescient in 2012 when conservative trends inside the church led to a rift with Catholic Campaign for Human Development over CCI's confrontational tactics.

In 1993, during a particularly lean budget year, Fagan and staff went on unemployment, working without pay. The experience led to a dues-based membership model in 1995. The new structure gave people a stake in the organization for the first time, but it was a sharp departure from the organizing tradition CCI came from.

Today, nearly 40% of Iowa CCI's $1.8 million budget comes from individuals. Its membership model and 501(c)(4) political arm have been widely adopted across the People's Action network.

Fagan's personal approach to faith and organizing extended to his family.

"Dad was always the one I called to come pick me up when I was sick at school," said his oldest daughter, Bridget Fagan-Reidburn. "He would come home for dinner and tell us stories about the campaigns he was working on. I used to go on every action. For me, CCI was the church."

In 2009, six years after he had stepped down as executive director, Fagan was still working for CCI as a special projects director.

"We went to this huge apartment complex and started knocking on doors," said Sharlin Aldao-Carrillo, who was CCI's newest immigrant organizer at the time. "We went around asking, 'Do you have any problems with the way your boss treats you?' "

They met a dozen laundry workers with wage theft complaints, which led to planning meetings, a direct action, and public meetings with state and federal regulators. The workers won back almost $10,000 in stolen wages, and kickstarted a campaign that continues to this day.

"Joe loved having meetings and I loved having meetings with him, because we would go over everything step-by-step," Aldao-Carrillo said. "I still do everything the same way today. It was the honor of a lifetime to have known and worked for Joe Fagan. He was a lion in the world of community organizing, a godfather."

[David Goodner is a Catholic Worker from Iowa City and worked for CCI from 2009 to 2014.]