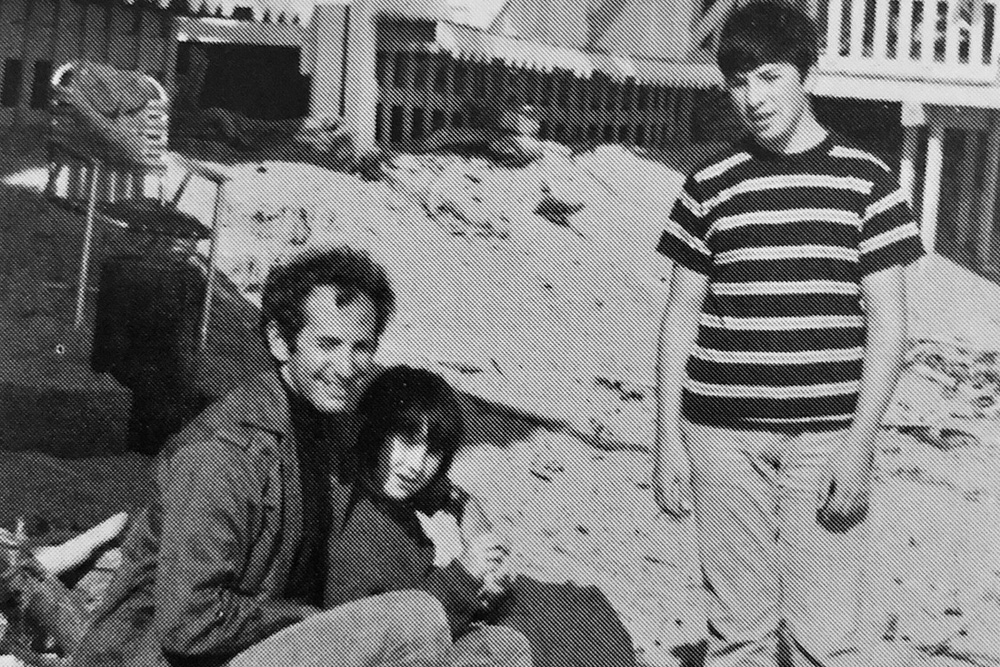

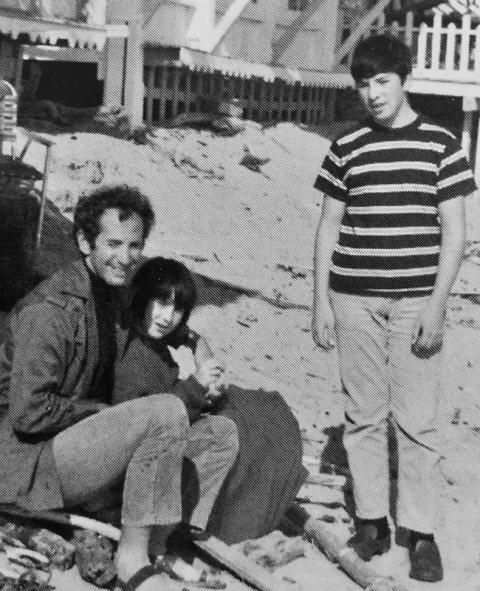

Robert Ellsberg, right, at age 13, with his father Daniel and sister Mary in a 1969 photo. In autumn of that year, Ellsberg agreed to help his father photocopy documents that came to be known as the Pentagon Papers. (Courtesy of Robert Ellsberg)

Editor's Note: Daniel Ellsberg, known for his 1971 release of government papers about U.S. operations in Vietnam to the media made him one of the most significant whistleblowers in U.S. history, helping to end a war and eventually take down a president, died June 16 at 92.

We are republishing this 2019 story in which NCR executive editor Heidi Schlumpf interviewed his son, Robert Ellsberg.

The autumn of 1969 has been on Robert Ellsberg's mind lately, as the 50th anniversary of a life-changing request from his father approaches. A half century ago, as a 13-year-old, Ellsberg agreed to help his dad photocopy documents from a government report he had worked on.

Those documents, which came to be known as the Pentagon Papers, revealed the United States' role in the build-up to the Vietnam War and the lies told to the American public and to Congress about U.S. actions in the region.

Daniel Ellsberg's 1971 release of those documents to the media made him one of the most significant whistleblowers in U.S. history, helping to end a war and eventually take down a president.

Now, as another, yet-unnamed person has brought to light information about alleged misdeeds of the current president, the younger Ellsberg — a longtime Catholic writer and publisher — is again reminded about the importance of truth-telling, the price that whistleblowers pay and the power of one person's actions.

In October of 1969, the elder Ellsberg, a former Marine who had worked as a high-level military analyst for the Rand Corporation, had been honest with his son, describing their copying of classified documents as an act of civil disobedience in the tradition of Henry David Thoreau and Mahatma Gandhi.

"He wanted me to be a witness to what he was doing," Ellsberg told NCR. "He hoped that as a young person, I would see that you might have to take risks, to be willing to pay a price for what you believe in, for what you feel is a higher good."

The now-63-year-old son got the message. His role as "minor collaborator" in that historic action ultimately inspired a career about "people who might similarly inspire and encourage imitation," he said.

After working with Catholic Worker co-founder Dorothy Day near the end of her life, Ellsberg went on to eventually edit her diaries and letters. In his 32-year career with Orbis Books, he also has edited and published truth-tellers from the margins of the Catholic community and thus significantly influenced the Catholic conversation in this country and around the world.

Robert Ellsberg, longtime writer and publisher of Orbis Books, has edited Dorothy Day's published diaries and letters, and is a former managing editor of The Catholic Worker. He is pictured in 2012 file photo. (CNS/Courtesy of Maryknoll Fathers and Brothers)

Whistleblowing 101

Whistleblowing is different from leaking, which Ellsberg calls the "currency of influence and interagency rivalries in Washington." While the latter is motivated by personal advantage, whistleblowing is instead motivated by a sense of the public good.

A whistleblower is someone from within an organization who brings to light waste, fraud, abuse, criminal behavior or other illicit activity. Some organizations, like the federal government, have official channels for such reporting, while other whistleblowers make the information known publicly, often through journalists. The Catholic Church has had its share of whistleblowers throughout the decadeslong sex abuse crisis.

Whistleblowing, or as Ellsberg prefers to call it, "truth-telling," always involves questions of loyalty. His father, as a former analyst with the highest security clearances when he had worked in the Pentagon and for the State Department, had pledged to keep government secrets. But he ultimately recognized a higher loyalty to the American people in exposing the truth.

Daniel Ellsberg initially intended to share the Pentagon Papers with Congress or others in government, but when no one was interested, he gave them to The New York Times and The Washington Post. Although the Nixon administration tried to stop the Times from publishing them, the U.S. Supreme Court eventually ruled in the Times' favor, in a major First Amendment victory.

"It's remarkable how few examples there have been of those who have deferred from that very limited idea of loyalty to recognize higher loyalty."

—Robert Ellsberg

"Those who work in hierarchal organizations are often made to believe that their highest loyalty is to the person they report to, or the good of the organization, or the good of the party, or the policies that their administration is serving," Robert Ellsberg said.

"It's remarkable how few examples there have been of those who have deferred from that very limited idea of loyalty to recognize higher loyalty," he said.

Similar issues are at play with the unidentified whistleblower who reported President Trump's alleged attempt to strong-arm the new Ukrainian president into investigating Trump's political rival in exchange for military aid — and the White House's attempts to cover up that communication. Trump has denied the allegations, made public in late September, although the administration's release of a transcript of the pertinent phone conversation indicates Trump did make the request.

Ellsberg believes it is important to note that public servants in the United States take an oath of loyalty to the Constitution, not to any individual leader. Even so, whistleblowers are often seen as snitches or traitors.

Trump has compared the current whistleblower's sources to spies and alluded to a time when such traitors were executed, despite the fact that current law provides channels for intelligence whistleblowers and protects them from retaliation.

Of course, whistleblowers must always weigh the possible consequences of their actions. His father held back parts of the Pentagon Papers that dealt with the then-current peace negotiations, so as not to be accused of compromising them, Ellsberg said.

"The question, as my father would say, is: 'Has more damage been done, more lives put at risk, because of people revealing the truth, or by keeping secrets?' "

Daniel Ellsberg, in a 2008 photo (Flickr/Christopher Michel, CC by 2.0)

Truth and consequences

There was no Whistleblower Protection Act in the 1970s to protect Daniel Ellsberg. But he was ready to accept the consequences of his actions, which he knew could include persecution, loss of his livelihood and even loss of his freedom.

Whistleblowing takes an incredible toll on families, financially and emotionally. Many marriages do not survive. Daniel, who had already been divorced from Robert's mother, had remarried and had the full support of his new wife, Ellsberg said.

Still, "you become a kind of leper that no one wants to touch or be close to. You're contaminated," said Ellsberg. "That was no big loss for my father. He felt he had kind of awakened from the spell of feeling that his ambition or highest calling was to serve in a future administration."

But that didn't mean there weren't serious consequences.

"Nixon did not want to rely on the courts to stop my father.

It wasn't just that they wanted punish my father for releasing the Pentagon Papers.

There was a feeling he had to be shut up. [Nixon] basically wanted to destroy the guy."

—Robert Ellsberg

Daniel eventually turned himself in and was indicted under the Espionage Act, facing up to 115 years in jail. At the time, Nixon's National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger called Ellsberg "the world's most dangerous man" (the name of a subsequent documentary about Ellsberg).

Fifteen-year-old Robert (though not his his younger sister Mary, who had also assisted with photocopying) was subpoenaed to testify before the grand jury. He was nervous he would be called as a witness, either for the prosecution or defense.

During the trial, it was revealed that a secret White House team — the so-called "Plumbers" —had burglarized the office of Ellsberg's psychiatrist to try to unearth information to discredit him. Citing governmental misconduct and other illegal evidence gathering involving wiretapping, the judge dismissed the case.

These same members of the Plumbers would go on to orchestrate the break-in to Democratic National Committee's headquarters.

"Nixon did not want to rely on the courts to stop my father," Ellsberg recalled. "It wasn't just that they wanted punish my father for releasing the Pentagon Papers. There was a feeling he had to be shut up. [Nixon] basically wanted to destroy the guy."

Ellsberg remembers being scared for his father's life and later learned of a White House plot to "incapacitate" his father. "It was clear that even before Watergate, the Nixon administration was capable of taking extreme measures against enemies, and it was clear they regarded my father as a particular enemy."

The country was still at war, and prominent political leaders had been assassinated. "It was a violent and scary time," Ellsberg recalled.

"I never doubted that my father had done the right thing, but it took a toll emotionally in a lot of ways," he recalled. "It churned up a lot of conflicting emotions."

To escape, Ellsberg applied to become a foreign exchange student and left the country during most of his father's trial.

Raised in the Episcopal Church, he began to study and be inspired by Gandhi, as his father had been. After two years at Harvard, he withdrew to travel to India, but a state of emergency in the country foiled that plan.

Instead he moved into a Catholic Worker house, where he met Dorothy Day, and his "life took a very different direction," including his own conversion to Catholicism.

Two generations of truth-telling

His father's courageous whistleblowing was more informed by moral and ethical considerations than by religious ones, Ellsberg said. (Daniel left the Christian Science religion as a teen.) But Daniel's own father supported his son's civil disobedience, Ellsberg said, adding that his grandfather once quoted the Gospel of John in explanation: "You shall know the truth, and the truth shall set you free."

Truth and truth-telling have continued to be part of Robert Ellsberg's vocation to "advance God's kingdom of love and truth," he said. After serving as editor of the Catholic Worker newspaper, he returned to Harvard to finish his undergraduate degree and began studies in the doctoral program at the Divinity School, eventually earning a master's in theology.

He has been with Orbis Books for more than three decades, which he feels is "the greatest contribution I have been able to make to a better world." The publishing arm of the Maryknoll Fathers and Brothers, Orbis is known for its books on liberation theology, peace and social justice.

During his career, Ellsberg has edited authors such as the late James Cone, founder of black theology; torture survivor Sr. Dianna Ortiz; death penalty activist Sr. Helen Prejean and Catholic Worker James W. Douglass, who has written about the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. Ellsberg also has edited or published 25 books by or about Pope Francis.

From left: Daniel Ellsberg, daughter Mary and son Robert, in a 1969 family photo (Courtesy of Robert Ellsberg)

He also helped his father with his memoirs, including Secrets: A Memoir of Vietnam and the Pentagon Papers in 2002 and The Doomsday Machine: Confessions of a Nuclear War Planner, published in 2017 by Bloomsbury USA.

"I felt that there was nothing more I could do to contribute to the cause of peace in the world than to help him with that book," Ellsberg said.

The younger Ellsberg also is the author of six books on saints, a contributor to daily reflections from Give Us This Day and tweets regularly about the saint of the day. His fascination with holy people "goes all the way back to the inspiration of my father and the people who inspired him," Ellsberg said.

He has always been fascinated by "the idea that the example of great and heroic figures enlarges our moral imagination and our capacity to envision the things we might do," he said. "If we see faith in action or moral principles lived out, it has a tremendous impact and influence on people."

He also is not afraid to tweet about the lack of heroism in the Oval Office and the cruelty of many policies coming from it. Recently, that has included a series of satirical tweets with the hashtag #TolstoysTalesofTrump, which highlight the president's narcissism and moral flaws.

Daniel, now 88, also continues to be a model and supporter of truth-telling and whistleblowing, including the whistleblower in the Trump/Ukraine affair.

One of his messages: blow the whistle sooner rather than later.

"My advice would be to do what I wish I had done in 1964 and didn't do," Daniel told Anderson Cooper on CNN Sept. 30. "Do what it took me five years to do. And don't wait that long, until bombs are falling on Iran, or another war has started, thousands have died."

His closing advice to the Trump whistleblower was to "face the possible personal consequences, which could be very severe, of telling the truth to Congress and the press."

That courage to tell the truth, even if though he thought it meant he might never see his children again, except through a Plexiglass window in prison, is what his son will remember.

"That is his legacy," Robert said. "All it takes is the power of one."

[Heidi Schlumpf is NCR national correspondent. Her email address is hschlumpf@ncronline.org. Follow her on Twitter @HeidiSchlumpf.]

Advertisement