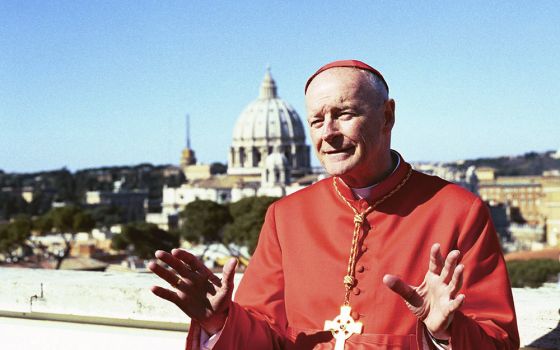

Pope John Paul II embraces Cardinal Theodore E. McCarrick of Washington after placing the red biretta on the new cardinal during consistory ceremony in St. Peter's Square at the Vatican Feb. 21, 2001. A Vatican report details the late pope's involvement in the appointment of McCarrick as archbishop of Washington. (CNS photo/Arturo Mari, L'Osservatore Romano)

The recent report detailing the Vatican’s response to the scandal surrounding ex-Cardinal Theodore McCarrick shows why it’s a mistake to canonize popes (or anyone) quickly after their deaths.

According to the Vatican report released last week, Pope John Paul II received warnings about McCarrick from Vatican officials and New York Cardinal John O’Connor in 1999. Two years later, McCarrick was installed as archbishop of Washington, D.C.

John Paul was beatified in 2011, six years after his death, and was made a saint three years later.

It’s not just popes: The church needs more time to examine any person’s life. The people of Argentina, for example, wanted to canonize Eva Peron immediately after her death in 1952. At the time, thankfully, the mandatory waiting period before the canonization process could begin was 50 years. Though she is still revered by many Argentines, Peron’s reputation has been clouded in recent years by accusations that she and her husband harbored Nazis after World War II.

John Paul reduced the waiting period from 50 to five years, because he wanted to canonize individuals who were still relevant to today’s generation. His successor, Pope Benedict XVI, waived even that for John Paul’s canonization in response to popular demand.

As a result, when John Paul was canonized a mere nine years after his death, independent historians did not have access to the secret files of the Vatican, so it was impossible for outsiders to judge his cause. As more information is disclosed, questions are raised about his actions.

Canonizing popes is a special problem because their canonizations are more about ecclesial politics than sanctity. Those pushing for sainthood are their fans who want their pope’s legacy to be reinforced. It is a vote for continuity against change, as elevating a pope to sainthood makes it more difficult to question and reverse his policies.

Politically, it is difficult to oppose the canonization of a pope because opposition is portrayed as disloyalty. Those who openly or secretly oppose canonization are usually proponents of change.

As a compromise, two popes are sometimes made saints at once: Pope John XXIII was made a saint the same day John Paul was in April of 2014. Progressives liked John while conservatives liked John Paul.

Advertisement

The practice, meant to soothe friction between factions in the church, goes back to Pope Calixtus and Hippolytus (the first anti-pope) in the third century. Legend has it that these opponents, whose supporters fought openly in the streets of Rome, reconciled after being sent to the Sardinian tin mines by the pagan Roman authorities. Both were honored as saints by the church of Rome in an effort to unify the church.

The joint canonization of John XXIII and John Paul II similarly brought together liberal and conservative factions who had been at odds since Vatican II, which was initiated by John.

I would not be surprised to see Popes Francis and Benedict canonized on the same day within 10 years of their deaths.

The politics of canonizing popes aside, saints are supposed to be models for Catholics and others to imitate. How can anyone who is not pope really model him or herself after a pope — unless you are a cardinal who wants to be a pope?

My preferred candidates for canonization are lay people, especially married couples and young people. I would canonize the Rwandan students at Nyange Catholic Girls’ School who were beaten and killed by Hutu militants in 1997 when they refused to separate into Hutu and Tutsi groups. Their witness against genocide and for solidarity would mean more to young people than any pope.

Were these young women perfect? Not likely, but they don’t need to be: Saints are not perfect; they are also sinners. We need to remember that St. Peter denied he knew Jesus.

But when scandals like McCarrick’s become known, it makes people question the whole system. Which isn’t always a bad thing. When Josemaría Escrivá, the controversial founder of Opus Dei, was canonized in 2002, a Jesuit wag responded, “Well, that just proves everyone goes to heaven.”