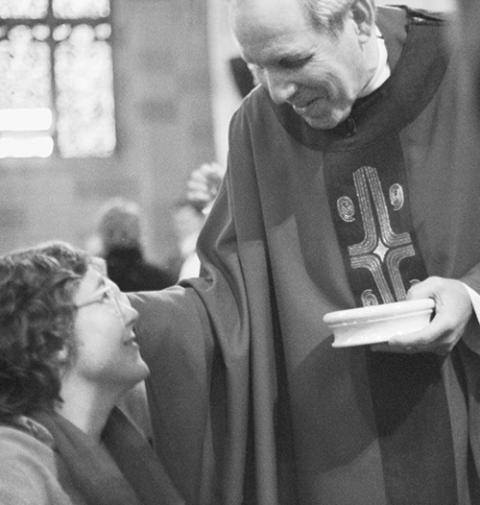

Myra Brown is the pastor of Spiritus Christi Church, which self-describes as "a progressive Catholic Church" with a strong emphasis on social justice. (©Jamie Germano – USA TODAY NETWORK)

Editor's note: According to a 2008 Pew Research study, one of 10 U.S. adults is a former Catholic. Some have moved on to other denominations, others have no church affiliation at all, still others have formed their own communities of former Catholics. In the final three parts of his five-part series, former NCR editor Tom Roberts looks at three different independent Catholic communities — how they came to be, and how they sustain themselves apart from the institutional church.

Myra Brown had a life-changing encounter with God while vacuuming in a home of friends where she was living.

At that moment in 1992, she was wrestling with a request to preach at a Sunday Mass at one of the Black Catholic parishes in Rochester, New York, where she was a member. She originally said no to the request from her pastor.

She thought, "You're kidding me. I can't do that. I'm Black, I'm a woman." And it was a Catholic Church. "We don't even do that."

But at St. Bridget's, it wasn't unusual to have women preach, so the pastor asked her to at least think about it. She said she would. And what she describes as more than a nudging from God led to a yes, and the beginning of a journey.

It has taken Brown, now 57, along an improbable path to her current position, ordained pastor of Spiritus Christi Church, which self-describes as "a progressive Catholic Church" with a strong emphasis on social justice.

Brown's story, as much as any individual's might, sheds light on characteristics common among independent eucharistic communities, outside the institutional Roman Catholic Church, that have emerged in the Catholic diaspora:

- An almost unqualified openness to everyone, including LGBTQ+ individuals;

- An acceptance of women leaders;

- An unconditional welcome to the Eucharist, including many who would be excluded in traditional Catholic parishes;

- An easy association with other Christian denominations and other faiths;

- A more democratic approach to decision-making than would be found in most Catholic parishes;

- A deep commitment to social justice expressed in robust ministries in the wider community.

While Pope Francis has said he had never turned anyone away from the Eucharist and has repeatedly called for the acceptance of all, including LGBTQ+ persons, into the Catholic family, that was hardly the case in the mid-1990s, when Corpus Christi Parish, the congregation that would spawn Spiritus Christi, was attracting wide attention for its progressive services and impressive ministries.

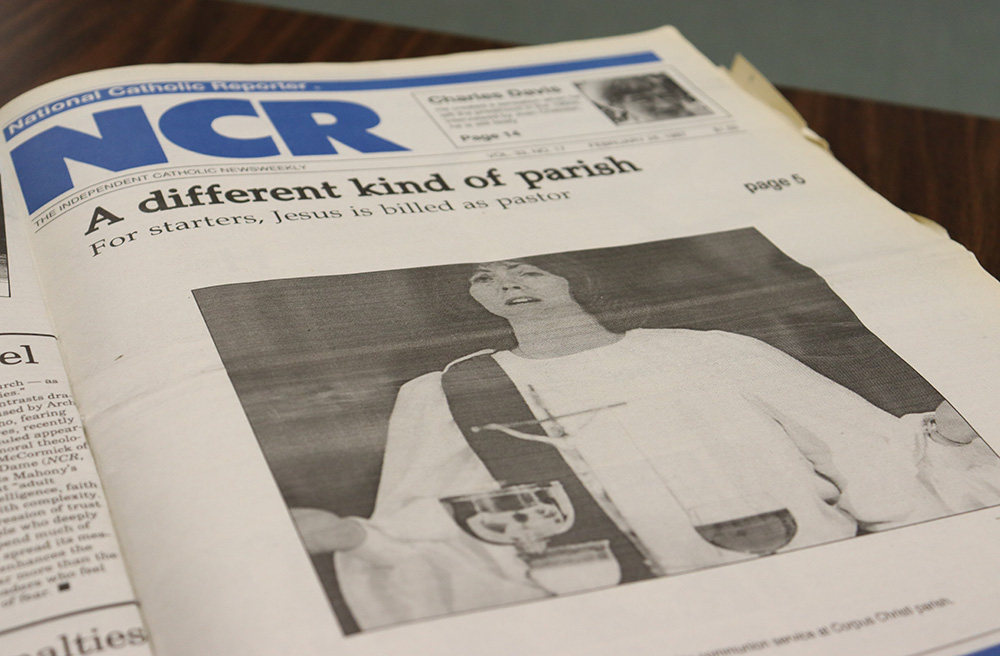

The cover of the Feb. 28, 1997, issue of NCR bore a photo of Mary Ramerman in a choir gown and half stole on the altar of Corpus Christi Parish. She and her husband, Jim, had landed there from Santa Rosa, California, 15 years earlier.

Mary Ramerman is seen on the cover of the Feb. 28, 1997, issue of National Catholic Reporter, for an article about Corpus Christi Parish in Rochester, N.Y. (NCR photo/Teresa Malcolm)

The couple, both theologically trained, were considering attractive offers from the Diocese of Stockton, California, and the Archdiocese of Seattle. They decided, however, to leave Santa Rosa for the icy winters and urban squalor of a section of Rochester after what Mary Ramerman described as a week that "was a life-changing experience."

That week was the job interview: no fancy digs, no firm salary offer, but a quick immersion into what the parish was about. They visited Dimitri House, the parish home for the homeless; Rogers House for ex-offenders adjusting to life out of prison; and a child care center in a former parish school. The Ramermans were sold.

The parish grew, as did its ministries, with Mary Ramerman named an associate pastor. It was a daring congregation. Fr. James Callan allowed several marriages of gay couples; everyone was welcome at the Eucharist, and Ramerman, who would be ordained a priest in 2001 by Bishop Peter Hickman of the Old Catholic Church, regularly preached and distributed Communion.

By the time NCR showed up to do a major profile of the parish, the tensions between parish and diocese were beginning to surface. "I don't think the article from NCR went down very well with the diocese," Ramerman said in a recent interview. But that wasn't the most significant point of contention.

In the summer of 1998, the staff met to discuss plans for the parish and ministries and "had no idea that that same day, the bishop was in Rome and coming back with plans to dismantle everything."

The bishop at the time, Matthew Clark, was widely considered a liberal, but even for him Corpus Christi had gone a step or two too far.

The dismantling came in stages. Callan was moved to another parish. Ramerman was forbidden from being on the altar or preaching if she wanted to remain on staff. She refused the conditions and was fired. Finally, the diocese fired six people in charge of running the parish's ministries.

What followed were meetings in which a large portion of the parish decided to break from the institutional church and begin a new community, eventually named Spiritus Christi.

Ramerman is often described as the founder, but she said in a recent interview that it was a team enterprise involving Callan and another priest formerly stationed at the parish, Fr. Enrique Cadena, both of whom decided to go with the new community. Ramerman, however, was founding pastor and Callan was listed as an associate.

Many members of the parish were among the 1,100 who formed the new community. The diocese considered all of the Catholics involved, including the priests, excommunicated.

Mary Ramerman, founding pastor of Spiritus Christi Church, arrives at a wedding in Stowe, Vermont, on Sept. 4, 2022. (Zack Griswold)

In a recent interview Ramerman, now retired as pastor, said the diocese gave three reasons for the dismantling of the parish:

- Having women on the altar and allowing them to preach;

- Inviting everyone to Communion without restrictions;

- Conducting weddings for gay and lesbian couples.

Brown was one of those who moved with Ramerman to the new community. Following her preaching debut years before at St. Bridget's Parish, her pastor, Fr. Robert Werth, had urged her to apply for a job at Corpus Christi, which was looking to add a person of color to its ministry staff. Reluctant at first because she was a practical nurse and had little training in Catholic ministry, she eventually did an interview and got the job.

If she was without formal training, she had a great deal of actual experience. She was a daughter of agriculture workers from Arkansas, who sought relief from awful conditions in the South only to find similar conditions in the North.

Brown was born in what she described as a migrant camp in Albion, about 30 miles west of Rochester. It was in that camp that she had her first contact with Catholicism. Young priests, she said, were sent to the camp as training and to minister to the mostly Black workers who lived there. She also attended summer schools at the camp run by Catholic sister.

It wasn't until much later, after her family had moved to Rochester, that members of St. Bridget's prevailed on Brown and several of her seven musical siblings to join the church musicians and choir. She became a regular churchgoer.

She also had friends deeply involved in Protestant Pentecostal and evangelical churches and she would attend those services, helping as an altar worker at special events and joining them when they witnessed on the street, and she prayed with people at events such as a Billy Graham crusade.

That's how she came to Werth's attention, who baptized her in 1987. She said people she had prayed with or ministered with would let him know.

In a telephone interview, Werth, who at St. Bridget's was a white pastor of a mostly Black congregation, said, "The Black community made me who I am today. They made me in terms of my style, my passion and my spirituality." And perhaps that's why he recognized gifts in Brown that others might not have seen.

He said he kept a copy of her baptismal certificate "because I knew she was going to be famous."

A degree of fame has come her way. She was one of the women featured in a June 2021 piece in The New Yorker magazine titled, "The Women Who Want to Be Priests: They feel drawn by God to the calling — and won't let the Vatican stop them."

She also was featured in a Washington Post article on her key role in easing tensions in Rochester following the March 2020 death of Daniel Prude, who had been restrained by city police.

"A respected community leader whose golden singing voice fills the church, Brown has the ear of both the city's leadership and its grass-roots advocates," according to the report. "A former nurse whose ministry is as tied to racial justice as it is to God, she emerged as a key channel of reason and understanding as tensions between police and protesters escalated, helping change the trajectory of the protests."

Advertisement

Brown had been given increasing responsibilities as a member of the staff of Spiritus Christi. Both Ramerman and Callan encouraged her to return to school. She received a bachelor's degree from Empire State College, where she focused on religion and social justice. She received a master's in theology from Colgate Rochester Divinity School.

Brown was ordained in 2017 by Christine Mayr-Lumetzberger, a former Benedictine nun who left the order and was later ordained a Catholic priest in 2002 and a bishop in 2003, reportedly by a Catholic bishop whose name has not been revealed.

Brown was named pastor in 2018 and led the congregation of 1,500 through the worst of the pandemic. She recently reported in a pastor's note that attendance at services, previously around 350 per weekend, had begun to pick up again post-pandemic. Callan is still on staff as one of two associate pastors.

Callan, in an email response to questions, described Spiritus Christi as "a Catholic Church without the discrimination ... that offers ALL the sacraments to people of every category."

The church, he said, employs a diverse staff of more than 50 people and an annual budget of $3 million. "We still value highly the treasures of the Catholic tradition, including the sacraments, the saints, Holy Days, the commitment to social justice, priority of the poor and marginalized, and the notion of the 'Real Presence' and 'Cosmic Christ.' "

The congregation is currently going through an elaborate process to determine whether to discontinue renting space and purchase a church property in a different part of the city. Brown was in favor of the change. The latest report delivered in a community email, however, lists estimates for purchase and necessary renovation and said the "parish staff and building exploratory committee" are now opposed to the move.

Brown, in an interview prior to the recent newsletter, said she would be agreeable with whatever the community ultimately decides. "If they vote no, I'll go with the people," she said.

In the nearly quarter of a century since that original split from the institutional church, time has provided a kind of karmic — or perhaps Christic — consonance to the story. Werth is now parochial vicar and resident at Corpus Christi Parish. He retains a great fondness for Brown, and she for him.

"I have no issues with anything she's doing down there," he said. "She's got integrity, she's intelligent. She's got everything you'd want in somebody."

Their relationship may mark one other characteristic of life in the Catholic diaspora — an understanding, perhaps once unthinkable, between those who leave and set up community outside the institution, and those who choose to stay.