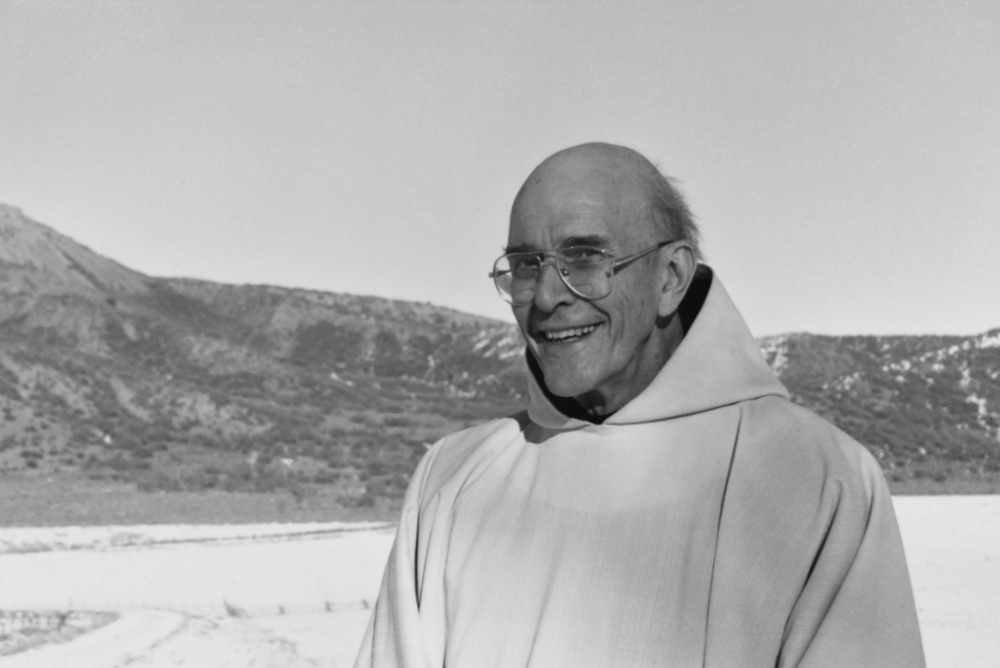

Trappist Fr. Thomas Keating: "He taught me the value of friendship with members of different religions. He taught me the value of silence and careful thinking." (NCR file photo)

Editor's note: This story was updated Nov. 1 at 10:15 a.m. Central time with details of the funeral and memorial services for Trappist Fr. Thomas Keating.

Trappist Fr. Thomas Keating, a global figure in both interreligious dialogue and Christian contemplative prayer, has died at the age of 95.

Keating died Oct. 25 at St. Joseph's Abbey in Spencer, Massachusetts, where he had been abbot from 1961 to 1981, and where he began his role as one of the chief architects of what is now known as centering prayer.

Internationally acclaimed for his extensive writing, lecturing and teaching on the contemporary practice of meditative prayer and on interfaith discourse, Keating had been transferred to the Spencer monastery infirmary on March 26 from St. Benedict's Monastery in Snowmass, Colorado, for enhanced medical support, St. Benedict's officials told NCR.

According to St. Joseph's Abbey, the funeral will be held in Spencer, with a private burial in Snowmass.

An Oct. 26 statement from Contemplative Outreach, the international organization co-founded by Keating, said, "It is with deep sorrow that we share the news of the passing of our beloved teacher and spiritual father."

"He modeled for us the incredible riches and humility borne of a divine relationship that is not only possible but is already the fact in every human being," the statement said. "Such was his teaching, such was his life. He now shines his light from the heights and the depths of the heart of the Trinity."

"Details will be forthcoming for a 24-hour, worldwide prayer vigil," the release added.

Keating, born March 7, 1923, was the third of four children born into an affluent New York City family, the son and grandson of prominent maritime attorneys. Presumably to follow a similar path, he launched his college education at Yale University in 1940.

His mother was a Bible reader and his father a lapsed Catholic. However, Keating found himself attracted to religion and told of sneaking out of his house to attend Mass.

In a 2014 documentary, "Thomas Keating: A Rising Tide of Silence," Keating recalled: "At 5, I had a serious illness. I heard adults in the next room wondering whether I'd live. I took this very seriously, and at my first Mass bargained with God: 'If you'll let me live to 21, I'll become a priest.' After that, I'd skip out early in the morning before school and go to Mass. I knew my parents wouldn't approve, so I never told them."

During his freshman year at Yale, Keating was increasingly drawn to church history and the writings of its mystics.

He transferred to Jesuit Fordham University in New York City, where he graduated from an accelerated curriculum in December 1943. While he was there, the spiritual director of a camp at which Keating had worked took him and others to visit Our Lady of the Valley, a Trappist monastery in Rhode Island, which was destroyed by fired in 1950.

"Keating was mesmerized," reports a 5280 magazine feature story on the monk.

A 20-year-old Keating entered the strict Trappist community at Valley Falls, Rhode Island, in January 1944. He was ordained a priest in 1949.

In the documentary, he describes the painful break from family and friends: "I broke communication with everyone I knew ... and prayed for my family daily. I felt the more austere the life, the sooner I would achieve the contemplative life I sought. I spent the next five to six years observing almost total silence. I couldn't leave. My only communication was with two abbots, neither of whom could give you any friendship or equality."

His grandmother, he said, wrote him from her sickbed: "I miss you so much. I'm lying here in bed, and I said to the nurse, 'If my grandson doesn't come home, won't you please just throw me out the window?' "

Unable to respond, Keating said he prayed harder for those he'd left behind.

Keating had resided at St. Benedict's at Snowmass for approaching four decades, not having left the campus for several years, St. Benedict's Abbot Joseph Boyle told NCR last July. Boyle died of cancer Oct. 21.

Recovering Christian contemplative prayer

Largely in response to the 1962-65 Second Vatican Council's call to religious orders for renewal, Keating and fellow Cistercian monks Fr. William Meninger and the late Fr. Basil Pennington (1931-2005), worked together in the 1970s to develop a contemplative prayer method that drew on ancient traditions but would be readily accessible to the modern world.

Keating's observation that many, notably younger persons, were being attracted to Eastern meditation practices helped spur his work to recover Christian contemplative prayer.

In-house issues and the contemplative work — focused on understanding silence as the language of God — reportedly created some uneasiness within the Spencer Trappist community. Some have described it as tension between monastic asceticism and contemplation.

A vote in 1981 on the continuance of Keating as Spencer's abbot was evenly split. Keating resigned rather than try to lead a divided community. He returned to St. Benedict's at Snowmass where he had served from 1958 to 1961 during its founding.

Freed of the Spencer monastery administrative demands, Keating not only expanded his work in centering prayer, but also spearheaded formation of the Snowmass Interreligious Conferences in late 1983, a yearly gathering of major figures of various religious backgrounds that ran for three decades.

During that same time frame, the growing popularity of centering prayer led to Keating directing retreats and workshops worldwide. That networking, in turn, sparked widening interest in organizational and educational structuring.

Out of that grew Contemplative Outreach Ltd., officially incorporated in 1986. Its website describes the network as consolidating "the three monks' experiment." Keating was its first president.

Fr. Carl Arico, a priest of the Archdiocese of Newark, New Jersey, also helped found Contemplative Outreach, and has done extensive teaching and outreach with contemplative prayer forms.

The priest told NCR a key insight he gained from Keating, whom he had known since 1969: Centering prayer "is more heartfulness rather than mindfulness. It is rooted in the Christian tradition, which emphasizes the relationship with Christ which is its source."

In the 2014 documentary on Keating, Arico describes attending one of the Trappist's first intensive centering prayer retreats at the Lama Foundation in San Cristobal, New Mexico, also attended by several others who would become founding members of Contemplative Outreach.

"I went on retreat with him in 1983," said Arico. "I went up to that mountain as Carl the priest. I came off that mountain as Carl the human being who happens to be a priest."

"The growth that has taken place in Contemplative Outreach is a miracle of God's grace and the power of prayer," Arico states on the organization's website.

The website also reports that Contemplative Outreach:

- Annually serves more 40,000 people;

- Supports more than 90 active contemplative chapters in 39 countries;

- Nurtures some 800 prayer groups;

- Teaches more than 15,000 people centering prayer and other contemplative practices through local workshops;

- "Provides training and resources to local chapters and volunteers."

While the organization's international offices are now located in Butler, New Jersey, its initial headquarters was the dining room table of Gail Fitzpatrick-Hopler, a member of the founding governing board and a trustee until 2014. Now retired, she was Contemplative Outreach executive director from 1985 to 1999 and was president from 2000 until 2015.

"My relationship with Father Thomas spans almost 40 years and we have shared many important moments in the growth and development of Contemplative Outreach, and it is hard to zero in on particulars," Fitzpatrick-Hopler emailed NCR.

She visited Keating at St. Joseph's Monastery in early July.

"It was very sweet to remember together and to have a few good laughs and shed a few tears. Over the years we have become good friends and companions on the contemplative path," she said.

In the Keating documentary, Fitzpatrick-Hopler says that, "within a few sentences," Keating "brought all my Eastern experience and my Catholic upbringing together all at once, and I recognized him as my teacher. It was almost not so much about what he said but just about who he is, and his presence. And he could just bring it together in such a way that meant something to me very, very deeply. ... Something really resonated."

Speaking in the documentary, Keating provides an insight into his overall sense of the divine.

"The gift of God is absolutely gratuitous," he said. "It's not something you earn. It's something that's there. It's something you just have to accept. This is the gift that has been given. There's no place to go to get it. There's no place you can go to avoid it. It just is. It's part of our very existence. And so the purpose of all the great religions is to bring us into this relationship with reality that is so intimate that no words can possibly describe it."

In addition to Contemplative Outreach, Keating has also served as president of both the Monastic Interreligious Dialogue and the Temple of Understanding. The Temple of Understanding presented the priest with its Juliet Hollister Award for "religious figures who bring interfaith values into the place of worship where the faithful congregate."

A 25-year participant in the Snowmass conferences, author and lecturer Rabbi Henoch Dov Hoffman said he and others treasured their friendships with Keating.

"He taught me the value of friendship with members of different religions. He taught me the value of silence and careful thinking," he said.

Ibrahim Gamard, the Sufi Muslim representative at the Snowmass Interreligious Conferences from 1988 to 2004, wrote in a statement provided to NCR: "Fr. Thomas was able to be nourished by other mystics and mystical traditions, not only for his own spiritual growth, but for the greater purpose of helping to revive Christian mysticism and contemplation — which is why he helped to develop and spread interest in Centering Prayer."

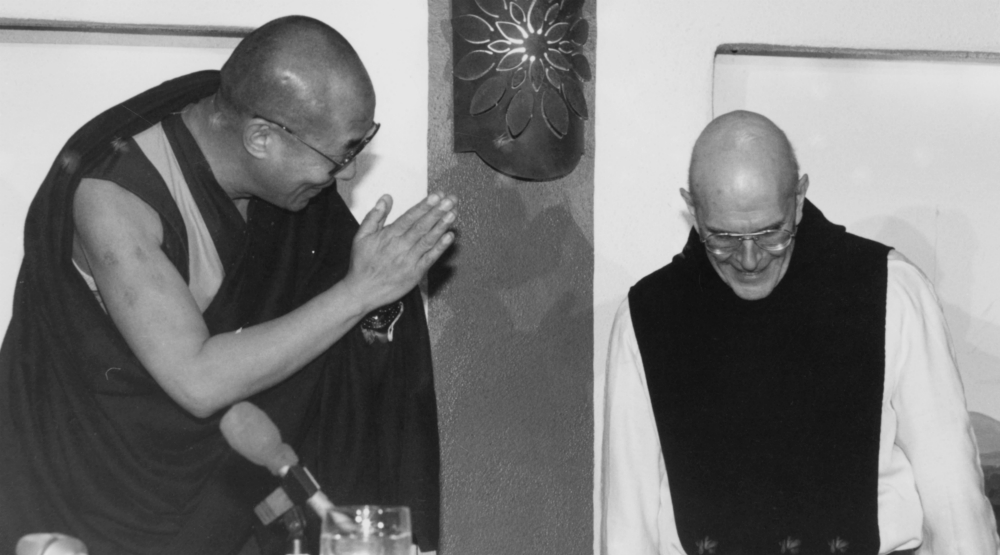

Over the years, Keating shared stages with many of the world's best-known religious thinkers and leaders, including the Dalai Lama and philosopher Ken Wilber.

The Dalai Lama and Trappist Fr. Thomas Keating in 1991 (NCR file photo)

Franciscan Fr. Richard Rohr, well-known author and speaker on spirituality, told NCR, "In my lifetime there are few priests or teachers who have both exemplified and taught an actual transformative spirituality as well as Thomas Keating."

"He changed lives and not just ideas. He changed minds and hearts and not just peoples' group affiliations," said Rohr, founder of the Center for Action and Contemplation in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

"He combined good theology with good psychology without compromising either of them," added Rohr. "We were personal friends and I will miss his company here in nearby Snowmass, but we will still have his love — and his books, which will always remain as spiritual classics."

Keating published nearly three dozen books, and was involved in several audio-visual projects.

Some of his best-selling volumes include Open Mind, Open Heart; Fruits and Gifts of the Spirit; St. Thérèse of Lisieux: A Transformation in Christ; Manifesting God; The Transformation of Suffering: Reflections on September 11 and the Wedding Feast at Cana in Galilee; and Divine Therapy and Addiction: Centering Prayer and the Twelve Steps.

One of Keating's most popular multimedia projects is the nine-hour, self-directed "Centering Prayer: A Training Course for Opening to the Presence of God," dubbed by one reviewer as "a monastery in a box."

Keating is featured in several YouTube video postings. The Contemplative Outreach website provides links to multiple brief video segments with the monk.

A significant collection of Keating's work is archived at Atlanta's Emory University, which also houses a collection of output from another famed Trappist, Fr. Thomas Merton.

Centering prayer draws its name from a reference in a Merton text.

Centering prayer in prisons

One piece in the 2014 documentary focuses on Keating's visits to Jens Soering, a convicted double murderer serving a life sentence.

Keating said that over time centering prayer greatly impacted Soering, who converted to Catholicism and has written several books and numerous articles on religion, prison reform, meditation and his own case.

The still-growing impact of centering prayer on prison populations is remarkable, according to practitioners and proponents of the method.

"Materials teaching this traditional contemplative practice, made current through Fr. Keating's work, are sent directly to prisoners in more than 600 prisons throughout the country," according to Ray Leonardini, a retired attorney who has been a chaplain at Folsom Prison in California for a decade and is founding director of the Prison Contemplative Fellowship.

Author of Finding God Within: Contemplative Prayer for Prisoners, Leonardini said more than "70 volunteers, countrywide, go into prisons on a weekly basis teaching Centering Prayer in the way outlined and described by Fr. Keating."

Advertisement

Leonardini emphasized what he called the "enormous power of Centering Prayer for personal transformation in the draconian context of the imprisoned."

"It revolutionized prison dynamics for practitioners then, and continues to do so even to a greater extent now," he told NCR in an email. "I believe, and I have witnessed, that the Centering Prayer phenomenon unleashed by the work of Thomas Keating and brought into the prison context has the power to counteract the dehumanizing forces encountered by the incarcerated. Thanks to Fr. Keating, we have not yet seen its limits."

According to Mike Kelley, who has a long history of centering prayer ministry at Folsom and who invited Keating there, "Fr. Keating was such a gentle, warm, kind person, a good listener."

Kelley described how during conversation with inmates or others the monk would "whisper softly under his breath an encouraging 'Yes.' "

Kelley laughed when recalling how an inmate told Keating that he "was happy as a hound dog" that the priest would visit them, then adding, "You are really famous, man, like Billy Graham. ... You have better things to do than visit us at Folsom Prison."

Kelley said that when Keating met with Arico following the Folsom visit, the monk said, "I will never have to wonder if what we are doing is worthwhile." Arico confirmed the anecdote.

Kelley recalled how Keating had visited five prisons in Northern California in a span of three days in 2000. "Fr. Keating clearly grew to love these folks and had a special place in his heart for each one of them. During that trip, Fr. Keating also visited dying inmates in a Vacaville prison that had a hospice facility," Kelley said.

Benedictine Sr. Mary Margaret Funk evolved from a Keating student into a well-known practitioner and teacher of Christian contemplative prayer, notably lectio divina, a meditative approach to praying the Scriptures.

As prioress of her Benedictine community in Beech Grove, Indiana, from 1985 to 1993, she had been charged with "retrieving, reclaiming and re-appropriating monasticism for women."

Keating was recommended. Funk traveled to Snowmass to meet him and was deeply impressed by the intense centering prayer retreats.

She later invited Keating to Beech Grove and "the whole community learned centering prayer."

"Thomas was a big guy and had a lot of presence, and could be very proper," said Funk, who later became a Contemplative Outreach faculty member. After her term as prioress, at the invitation of Keating she was seated on the board of Monastic Interreligious Dialogue. She served 10 years as executive director.

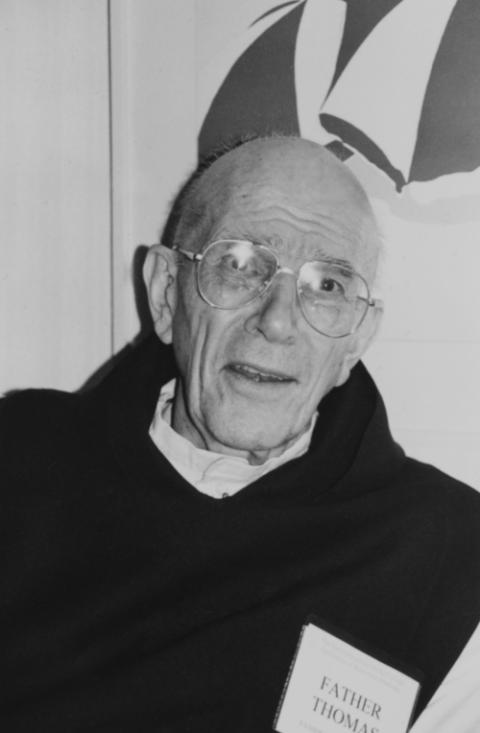

Trappist Fr. Thomas Keating: "He was not so much a conversationalist as he was a teacher." (NCR photo/Arthur Jones)

"He enjoyed the details of things," Funk said, noting that Keating could be "prone to long stories."

"He was not so much a conversationalist as he was a teacher, and he had definite opinions," Funk added. "And, frankly, no one ever changed his opinion, although he might capitulate once in a while. He was definite in his thoughts."

At the same time, she said, Keating "really did extend himself one-on-one to many people during retreats and in his travels, extraordinarily so. But, he was definitely a director, like an abbot even for lay practitioners."

"Thomas stayed in his own skin, in his own domain. He had his own organization and his very direct way of initiating his programs and retreats and courses of study," observed Funk, author of several books on contemplative practice and spirituality.

"He did have a mind that was quite sharp, quite excellent," she said. "He was probably a genius. Yet I don't think he read all that much; he did not read original languages like Greek or Hebrew, but he could penetrate deeply. He was one of those who go to the deepest levels of conclusions. He lived in his mind. He was fascinated with the search for insights and aspects of consciousness."

Funk praised Keating's "great affinity and deep loyalty to his friends." The downside, she added, was that he made himself totally accessible with little limitation to a "large inner circle."

"It could be a problem in that everyone had immediate access, and he would go with the last person he visited with," she said. "He would listen attentively, and each thought they had might shift his thinking, but he'd stay firm in his default original position."

Keating had "no love for linear organizations" and "an aversion to authority," she said, "which was ironic because he had a lot of authority and did not relinquish it."

The late Snowmass Abbot Boyle, under whose authority Keating had lived since Boyle was elected abbot in 1985, shared a different perspective in July.

When Boyle joined the Snowmass community in 1959, Keating was his superior and remained so "until the day of my simple vows, two years later," just before Keating was elected abbot at Spencer.

"So, my first experience of Thomas was as the superior who introduced me into the monastic life," Boyle told NCR.

Since becoming St. Benedict's abbot, Boyle said, he "had the custom of spending an hour with Thomas every Monday afternoon. That would include everything from spiritual discussion to particular leadership issues with me and even at times with issues he was dealing with. His counsel was always treasured."

"Actually, Father Thomas was a very easy person to have in community and he would not hesitate to ask permission for anything out of the ordinary that he wanted to do," Boyle added. "Of course, he was my teacher when I first entered, and as abbot I did not consider myself to be his teacher."

When Keating returned to St. Benedict's at Snowmass in 1981, said Boyle, "I imagined that he would use his time sitting quietly in one corner of the church meditating day and night. Instead, the Lord seemed to put it into his heart to start a new venture that would spread the contemplative practice among Christians and support them in it. As such he would fly around the country spreading that word wherever there was an audience desiring it."

Located on nearly 4,000 bucolic acres surrounded by the Elk Mountains, the Snowmass community of about 15 monks accommodated him.

"Though it is very unusual for a Trappist monk to be involved in any ministry like this, the monastic community here, and myself as abbot, felt that Thomas really did have a calling from God to do this ministry, and we supported him in it as best we could," Boyle said.

"This meant that Father Thomas' participation in the monastic life at Snowmass needed to be modified to accommodate this ministry," he continued. "But since we felt this was a response to God's call to Thomas, it did not adversely affect the community, but rather we encouraged him."

Boyle echoed what many said about Keating, underscoring the priest's "pastoral approach to people and their situations" and "gentle temperament."

"He was so easy to approach," the monk said.

Keating's temperament, approachability and intelligence clearly played a key role in the success of the Snowmass Interreligious Conferences.

"Participants met on a very personal level, not wanting any publicity, and just shared their own religious experiences," said Boyle.

Gamard, the Sufi Muslim representative, hinted at the intimacy and candor of the interreligious sharing, describing an incident during the 1995 conference when Keating "told us of some of his personal struggles, such as about a crisis of faith he was experiencing, regarding which he expressed in a poem that he read to us."

"With him in mind," Gamard wrote, "I later sent him some verses from Jalaluddin Rumi, the great 13th century Sufi Muslim poet, which I had translated from Persian — such as, '(God said), "That calling out 'God!' of yours is My 'Here am I!' And that neediness and painful yearning of yours is My messenger (to you). ... Beneath every 'O Lord!' of yours is (many a) 'Here am I' (from Me).' "

Keating wrote Gamard a month later when the priest "was undergoing a five-month retreat," Gamard stated, then quoted the monk's note to him: "I am grateful for your kindness in sending me your wonderful translations of Rumi, which I read with great gratitude and benefit. Many of the texts spoke to my general state of mind and heart. You have greatly refreshed me. ... I am indeed one with you in heart as I mull over these precious insights."

While little direct record of the conferences' conversations exists, a 2006 book, The Common Heart: An Experience of Interreligious Dialogue, offers a summary and analysis of the gatherings.

'A teachable, spiritual process'

Among the Snowmass Trappist community supporting the spread of centering prayer is Meninger, an original collaborator with Keating and Pennington.

Meninger's 1974 discovery of a dusty volume in the Spencer monastery library proved central in the development of centering prayer. The anonymous 14th-century The Cloud of Unknowing, notes Meninger's website, "presented contemplative meditation as a teachable, spiritual process enabling the ordinary person to enter and receive a direct experience of union with God."

According to the website, Meninger "quickly began teaching contemplative prayer according to The Cloud of Unknowing at the Abbey Retreat House. One year later his workshop was taken up by his Abbot, Thomas Keating, and Basil Pennington, both of whom had been looking for a teachable form of Christian contemplative meditation to offset the movement of young Catholics toward Eastern meditation techniques."

In an email to NCR, Meninger said Keating's work "represents the finest in the mystical Catholic tradition, with its origins in the earliest centuries of the church."

Keating, Meninger wrote, "was also a much beloved teacher throughout the world and will be long remembered in the hearts of mystics and contemplatives."

Long active in interfaith efforts, Bishop Joseph Bambera of Scranton, Pennsylvania, praised Keating's life work, successes of Contemplative Outreach, and the example of the Snowmass conferences.

Bambera, who was elected to a three-year term as chairman of the U.S. bishops' Committee on Ecumenical and Interreligious Affairs in 2016, told NCR in an email:

Among the many gifts Fr. Keating brought to the wider Catholic community, not least being the success he attained both in bringing the rich contemplative tradition of Lectio Divina — brilliantly taught as Centering Prayer — to a worldwide readership, and the establishment of Contemplative Outreach — an organization committed to the propagation of centering prayer, he was also a leading Catholic proponent of interreligious dialogue, cultivating ties of friendship and understanding between religions. One thinks, for example, of the Snowmass Conference that he instituted ... as a wonderful model of how to do interreligious dialogue in the post-Vatican II era.

In 2013, what was described as "the first reunion of religious leaders from one of the longest-running interreligious dialogues ever conducted" was convened at what was then the Cascadia Center in Mount Vernon, Washington.

Thirty-seven "spiritual pioneers and religious leaders" took part, including Keating and other several long-time Snowmass conference participants.

Lead host was Fr. William Treacy, then head of the Cascadia Center, and himself an interfaith work pioneer.

Treacy and Keating had been friends since 1975 when the Seattle archdiocesan priest traveled to St. Joseph's in Spencer to be tutored by the monk on centering prayer.

St. Joseph's Abbey in Spencer, Massachusetts (Wikimedia Commons/John Phelan)

"It changed my life of prayer and I introduced it into parishes where I served. In a world divided in so many ways, it can bring a sense of peace and unity," said Treacy, who at 99 still meditates a half hour each morning and evening.

"His passing is a loss for the whole human family and for me in particular," Treacy said.

Another presenter at the 2013 Cascadia assembly, Holy Cross of Chavanod Sr. Lucy Kurien, agrees.

Kurien, the globally honored founder of Maher ("My mother's home" in the Marathi language), a string of homes for the very poor in various parts of India, said Keating's "spiritual mentorship, advice and leadership have been invaluable to me" and that "listening to him has been a deep spiritual experience and inspiration."

"Father Thomas touched my heart deeply and assisted me greatly in my own vocation as a Catholic nun," shared Kurien, who first met Keating at a 2007 centering prayer conference in Houston. "His humor and joyful living made a strong personal impact in my life. Such grace and openness in a spiritual elder made me feel so comfortable in his company, and I felt I could share openly with him about my personal struggles, as well as the unique interfaith practices in my own project, Maher."

"Father Thomas could understand very well my struggles, and my deep conviction in cultivating interfaith and interreligious practices, which he always encouraged," added Kurien. "In view of this, I was able to start the Interfaith Association for Service to Humanity and Nature at Maher."

"I will forever be grateful for his profound guidance, kindness and monetary help towards Maher, and he will be in my heart and in my prayers forever."

[Dan Morris-Young is NCR's West Coast correspondent. His email is dmyoung@ncronline.org.]