A person in the Brooklyn borough of New York City attends a birthday vigil for George Floyd Oct. 14. Floyd was pinned down May 25 and died at the hands of a Minneapolis police officer. (CNS/Brendan McDermid, Reuters)

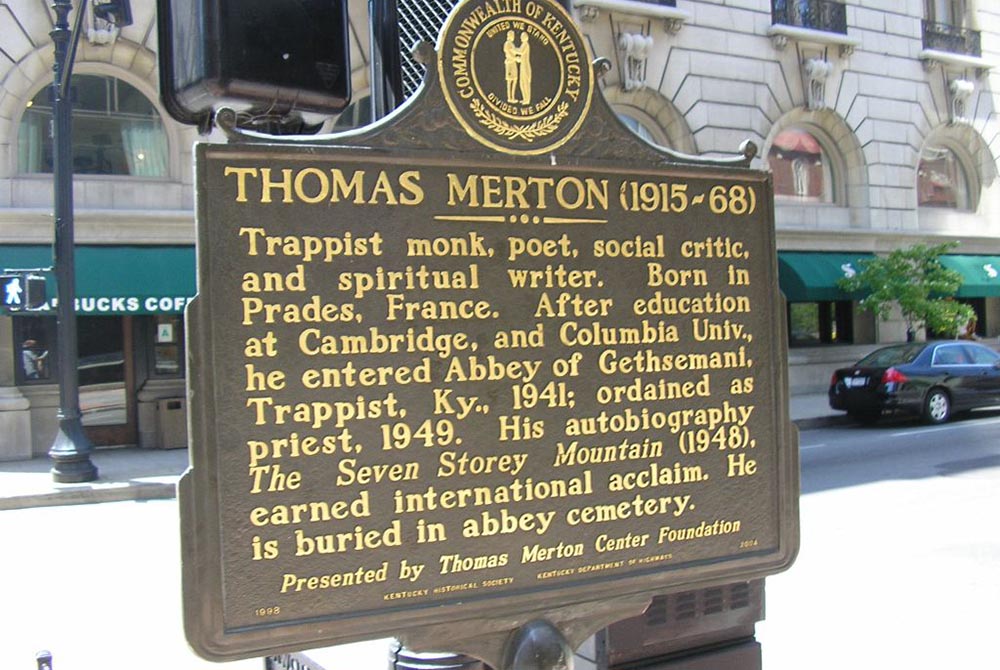

A marker commemorating Thomas Merton in downtown Louisville, Kentucky. Demonstrations took place in Louisville surrounding the police killing of Breonna Taylor March 13. (Wikimedia Commons/W.marsh, CC by SA 3.0)

He was a white guy, who spent most of his life alone in the woods in a then-Jim Crow region. But the words Thomas Merton, the Trappist monk, wrote on racial justice resonate as strongly today as they did when they were published more than a half-century ago.

"He was ahead of his time," Gregory K. Hillis, a professor of theology at Bellarmine University in Louisville, Kentucky, told NCR. "As a white Catholic, he got it, at a time when people didn't get it. ... It is remarkable how insightful he was."

Hillis is the author of a book exploring Merton's thought, to be published next year by Liturgical Press. He also teaches a course on the famous monk, one of four Americans cited by Pope Francis as exemplars during his address to Congress in 2015. The others were Dorothy Day, Abraham Lincoln and Martin Luther King.

Trappist Father Thomas Merton is pictured with the Dalai Lama in 1968. (CNS/Thomas Merton Center at Bellarmine University)

Merton is less well-known than the other three. At Bellarmine, however, he is a kind of college symbol. The institution houses the Thomas Merton Center, not far from the downtown Louisville site at Fourth and Walnut about which Merton wrote his famous mystical vision of God alive among the people he encountered on a rare trip outside the cloister. The center houses Merton's writings. It is about 50 miles from Gethsemani Abbey, the Trappist monastery where he spent most of his life.

While there, Merton, a prolific author, wrote unceasingly about the contemplative life, Eastern religions, and issues of war and peace that absorbed Catholic life during the Second Vatican Council and the general social ferment of the 1960s. But much of his writing on civil rights remained an afterthought, until the events of this summer, triggered by the Memorial Day murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis, placed a renewed emphasis on racial justice concerns. Merton's writings on race have garnered renewed attention among Catholic activists and academics, who gathered for a virtual Sept. 8 conference on the topic directed by Franciscan Fr. Dan Horan, professor at Catholic Theological Union in Chicago and NCR columnist.

Hillis told NCR that Merton was isolated from the tumult of his times, at least physically. Yet his eyes were opened to the routine injustices endured by Black Americans after his correspondence with such figures as James Baldwin, the famous Black essayist and novelist; Fr. August Thompson, a Louisiana Black Catholic priest who died last year, and John Howard Griffin, the white man whose Black Like Me, a chronicle of his travels after passing for Black, was a bestseller.

Merton's most provocative writings on the subject appear in an article he wrote in 1963 titled "Letters to a White Liberal," now praised for its prophetic vision. Merton's monastic life paradoxically provided insight into the issue, said Hillis.

"Merton, because he was isolated from the world, was able to look at the world with the kind of clarity others wouldn't have," said Hillis. He compared Merton's role as that of a good marriage counselor, able to clarify issues because he remained in many ways apart from them.

In "Letters to a White Liberal," Merton wrote that unless the nation came to grips with racism, "the survival of America itself is in question." In a reference to the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., Merton wrote using early 1960s language that the civil rights leader "clearly spelled out the struggle for freedom not as a struggle for the Negro alone, but also for the white man."

Merton added, "the sin of white America has reached such a proportion that it may call down a dreadful judgment, perhaps total destruction, unless atonement is made." He added, citing the long history of slavery and discrimination, that "white society has sinned in many ways. It has betrayed Christ."

And, in an appeal to white Christians, he wrote: "Most of us are congenitally unable to think black, and yet that is precisely what we must do." He called upon Catholic leaders, including bishops, to go beyond the usual responses of the era and embrace the call for change no matter the pushback: "We still want to please everyone with soft words and pleasant generalizations, which we convince ourselves are necessary for charity," Merton wrote.

Anne Pearson, a student in Hillis' class on Merton, told NCR that the monk's words spoke to her as a supporter of the demonstrations in Louisville surrounding the police killing of Breonna Taylor this past March.

Demonstrators in Louisville, Kentucky, march for Breonna Taylor Sept. 25. (CNS/Lawrence Bryant, Reuters)

"There are huge parallels," she said, noting that Merton's "Letters to a White Liberal" is "so applicable, it was shocking." She said that Merton's writings could be applied to today's church leaders, who she described as providing a disappointing response to the call for racial justice proclaimed by activists this year.

Merton's words resonate a half-century later, she said, "because he could listen" and "wasn't forming his ideas in response" to the critiques from activists.

Pearson admitted that her interest in Merton could be shaped by her own unique background. She is the daughter of Paul M. Pearson, director of the Thomas Merton Center at the college. Growing up, she attended lectures and conferences on the monk, and noted that most of those focused on issues such as contemplation and war and peace. His social justice witness on civil rights is often overlooked, she said, until now, as events bring Merton scholars and activists back to that part of his writings.

Macy Jones, another student in the Bellarmine Merton class, said she identified with the title of Merton's landmark essay on race.

"I identify as a white liberal. It made me question myself," she said, noting that involvement in changing conditions means more than posting slogans on social media.

Merton, she told NCR, "takes an historic lens. He is good at pointing out problems. He's not always good at solutions."

Like the title of his essay, Merton's words have largely made an impact on a relatively tight circle of Catholic academics and activists, most of whom are white. Most of the students at Bellarmine are white, while the Black student group on campus has provided activism on racial justice concerns, particularly over the Taylor killing in Louisville. Horan's event at Catholic Theological Union attracted an overwhelmingly white audience.

But that's OK, said Pearson. She said that Merton, who died in 1968, was directing his attention to white America. Black Americans, she noted, already know the lessons, having lived it for hundreds of years.

She said, "The African American students don't need to hear this. It's more important for white students to be aware of it." She suggested that the lesson of Merton's writings is for her "to play the role I should have as a white person."

Advertisement

Fr. Bryan Massingale, a theology professor at Fordham University, is an African American who has written extensively on the Catholic Church and race issues. He told NCR via email that Merton got race issues because he listened.

"Merton took the time to actually read Black thinkers and writers. And not just the ones that make white people comfortable. He read Malcolm X. And Martin Luther King. And James Baldwin. He read them not to refute their arguments, but to be informed by them. He read them with an openness to being seared by what they had to say, with an openness to being converted to new ways of thinking and acting," said Massingale.

By contrast, he said that most white Catholics, particularly white bishops and priests, have not read contemporary writers on the Black experience. Massingale is a priest of the Milwaukee Archdiocese.

"The bishops of the United States wrote a pastoral letter on racism in 2018 that didn't even mention the Black Lives Matter movement. Rather than being informed by the contemporary Black experience, most white Catholics are, in my view, blissfully ignorant of it, defensively resistant to its realities, or implacably hostile to any engagement with it," he said.

Ultimately, Merton was led by prayer in developing his thinking, said Massingale.

Contemplative prayer is "rare in white US Catholicism. It is, at best, seen as the preserve of monks and women religious," he said. "As someone who has made a directed retreat every year for the past 30 years, I am usually one of only a handful of men and priests who are ever present. The spiritual immaturity of many Catholics, including many of its priests and bishops, is an obstacle that keeps them from grasping the truths that Merton saw about American racism, and then acting with prophetic courage to challenge this evil."

Merton "didn't just say prayers or engage in rote spiritual exercises," Massingale said. "His prayer life was transformative. He was able to recognize that white racial identity, with its pretense to superiority and dominance, was in fact bondage to a false self. It was an illusion of the worst kind that blinded white people to the beauty of Black people as images of God."

Merton, he said, was led "to understand that he could not be in an authentic relationship with God while being complicit with the racial consciousness of white America."

Massingale's view echoes Merton's own, as the monk wrote in "Letters to a White Liberal": "The Negro problem is really a white problem."