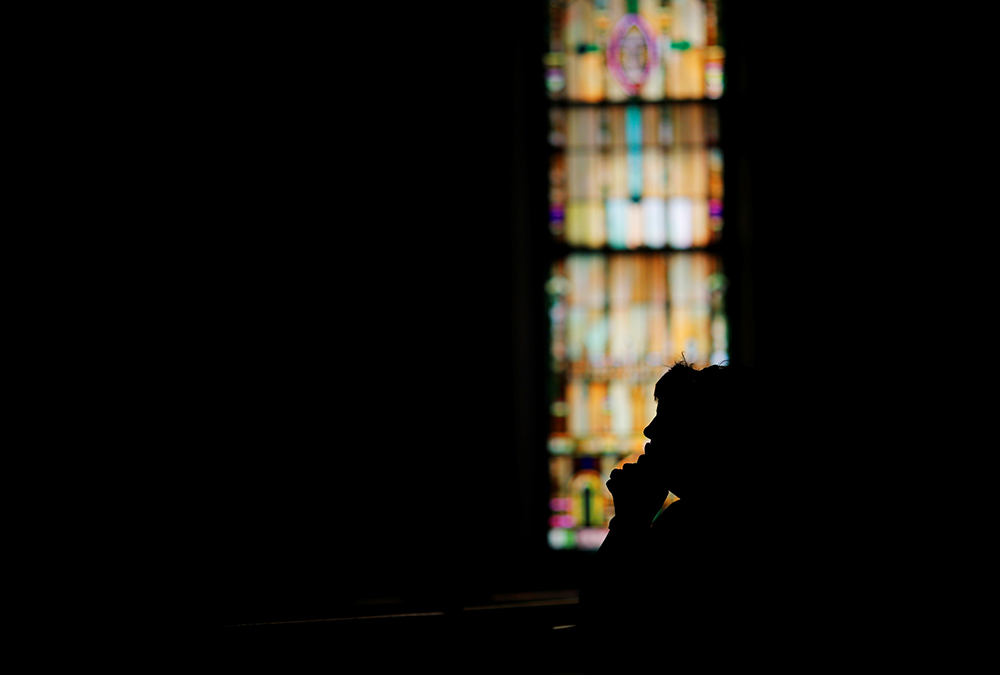

A woman prays in St. John the Baptist Catholic Church in Quincy, Massachusetts, in 2017. Parishes in the Boston Archdiocese in 2004 underwent a "reconfiguration" that closed 65 parishes. Some seven years later, the archdiocese began a restructuring process under an 11-year plan that includes having one pastor for multiple parishes. (CNS/Reuters/Brian Snyder)

Arthur McCaffrey fought for about a decade to keep his parish in suburban Boston open.

But in 2015, St. James the Great Parish in Wellesley was demolished. The site is now home to the Boston Sports Performance Center, a large recreational center complete with a hockey rink, swimming pool and indoor field.

St. James was one of nine Boston-area churches that kept a continuous vigil to prevent their parishes from being shuttered by the Boston Archdiocese in the wake of the sex abuse crisis that was brought to light in 2002 by The Boston Globe. Parishioners occupied the churches for years, 24 hours a day, seven days a week, 365 days a year.

St. Frances X. Cabrini in Scituate was the last of the vigil holdouts. It closed in 2016, after parishioners spent almost 12 years in vigil and exhausted their legal appeals to the Vatican and in civil courts. Their civil case reached the U.S. Supreme Court, which refused to hear the case, letting stand a lower-court ruling that stated that the archdiocese owned the church's property and the parishioners who were keeping vigil were trespassing.

Now, four years later, the Vatican's new document on pastoral care raises the question of whether parishioners have more legal recourse within the church to keep their parishes open. The answer appears to be yes.

The 22-page document from the Vatican's Congregation for the Clergy, released July 20, is titled "The pastoral conversion of the parish community in the service of the evangelizing mission of the church." It discusses the role and structure of parishes in today's digital age, where the concept of a fixed parish that covers a certain area may be outdated. One topic the document addresses is the closing of parishes.

"It is an instruction, and instructions are by definition not law," said Robert Flummerfelt, a canon lawyer in Las Vegas. "But what they are is information on how to apply the law."

Flummerfelt says he is encouraged by the document because it spells out reasons a bishop cannot close a parish — namely, "the lack of clergy, demographic decline or the grave financial state of the diocese."

Former parishioners at the now-closed St. Frances Cabrini Church in Scituate, Massachusetts, are seen holding a vigil in May 2015. (CNS/The Pilot/Christopher S. Pineo)

Those were all reasons Cardinal Sean O'Malley, archbishop of Boston, gave in 2004 when he announced the archdiocese's "reconfiguration" plan, which called for 65 of the archdiocese's 357 parishes to be closed.

The new Vatican document states that a diocese's financial distress, lack of priests and declining parish enrollment may be "conditions within the community that are presumably reversible and of brief duration."

"A lot of time, it is about the money," Flummerfelt said. "The financial viability of the parish on a practical level is the concern."

He said the lack of money was the central issue in the last four parish closing cases he has handled.

But now with the instructions, parishioners have additional protection that may prevent their parish from being closed or even being considered for closure, he said.

The document also states the bishop must issue a separate "decree" for each parish he decides to close. One decree cannot cover multiple parish closings. Furthermore, the instructions stipulate that a bishop must be clear and specific about the reasons for closing a parish.

A bishop will have to be more "circumspect," Flummerfelt said.

Fr. Jeffrey Fleming, moderator of the curia for the Diocese of Helena, Montana, said with the instructions, bishops must come up with "long-term" reasons to justify why a parish isn't viable and should be closed.

Still, financial problems can present existential crises, and Fleming realizes that his diocese may face a situation that is more common in the Northeast and the Midwest: declining church enrollment and finances that prompt a bishop to close a parish.

Fleming points to the example of Butte, Montana, which was once a bustling mining town with many Irish immigrants. Now the mining industry has declined and the Catholic population is older and falling in number. The town of about 33,000, big by Montana standards, has four parishes.

Advertisement

In the Boston Archdiocese, McCaffrey said parishioners offered O'Malley a solution to keep parishes open — let parishioners run the parishes and have fewer priests serve more parishes, much in the same way a firehouse may serve multiple neighborhoods. He said O'Malley has since adopted that model, but rejected it at the time St. James parishioners and others presented it.

Fr. Paul Soper, secretary for evangelization and discipleship as well as director of pastoral planning for the Boston Archdiocese, said that in 2004 the archdiocese didn't have enough personnel to staff all of its parishes. He noted, "There's nothing in the [new Vatican] document that said it is retroactive."

He added that the archdiocese in 2011 embarked on an 11-year plan that included having one pastor for multiple parishes. That plan wouldn't have been possible, he said, if the restructuring hadn't taken place, because without the parish closures, the archdiocese would have faced an "emergency" situation and wouldn't have been able to take the gradual approach of the 11-year plan.

The new Vatican document encourages parishes to find ways to keep churches open such as having a "grouping of parishes" in an area and outlines situations where one priest may be responsible for such a grouping.

The scenario of covering multiple parishes with one priest is a familiar one in the Helena Diocese, which covers the western third of Montana, an area of 52,000 square miles, which is almost the size of the entire state of New York.

The diocese has 57 parishes and 38 mission churches and 79 priests, including retired priests, Fleming said. Priests often travel great distances to ensure that Mass is celebrated at every parish or mission at least once every weekend, he noted.

The Cathedral of St. Helena in the Diocese of Helena, Montana (Wikimedia Commons/Lee Zurligen)

Fleming himself is based in Helena, the seat of the diocese, and every Sunday, he travels 120 miles roundtrip to offer two Masses — one at St. Thomas the Apostle Parish in rural Helmville, 60 miles west of Helena, and another at St. Thomas the Apostle's mission church, St. Jude the Apostle in Lincoln. Fleming is the administrator of the parish, and he said laypeople take care of the churches during the week.

Previously, Fleming served at four parishes concurrently in Missoula, an assignment that included serving as the Catholic chaplain for the University of Montana.

Without being onsite himself, Fleming relies on laypeople to take care of the day-to-day operations of a parish and to be the "eyes and ears of the parish," so that he knows what is happening.

That is, he said, what the new Vatican instructions encourage — the broad participation in parish life by all, not just a priest.

For some, though, the new Vatican instructions don't go far enough in handing the reins of a parish to the laity.

The document says a pastor may be responsible for more than one parish only when that is necessary. Alternatively, a group of priests may be responsible for more than one parish.

When a diocese faces a shortage of priests, it may appoint a priest to be an administrator of a parish, but that should be a temporary state, the instructions say.

A layperson can be appointed administrator only in "extraordinary" circumstances, the document says, adding that in such cases a deacon would be "preferable" to a layperson or consecrated man or woman.

"I read it as just pretty more of the same," McCaffrey said of the instructions. "They're handing out what I could call an HR policy of a large corporation, saying, 'Hey, the priest is the boss, don't forget it. ...

"This simply is the Vatican reiterating an established policy that has been on the books for a while, but in a response to more frequent requests to understand why parishes are being closed, they are reissuing this policy document," he added.

"At the end of the day, it's a rejection of more lay participation in parish running, in parish planning, in parish administration. The basic message is, 'The priest is the boss, and you guys aren't going to be able to take over some of his roles.' "

But Cardinal Beniamino Stella, prefect of the Vatican's Congregation for Clergy, told Vatican Insider that the document shows that every Catholic should feel he or she has a role and responsibility in the church's mission to evangelize.

Fleming said that the document stresses that every member of a parish is called to be a "witness of Christ, a light to the world."

"Pope Francis is calling us to be a church that looks outwardly, not just inside the church itself," Fleming said. "To bring more people to the table, especially the poor and marginalized."

[Mark Nacinovich, a New York-based writer and editor, was formerly managing editor of the Brooklyn Tablet and has also written and edited for Catholic New York and the New York Post. He is a graduate of the University of Chicago.]