People hold pictures of four American churchwomen during a Dec. 2, 2015, memorial service to commemorate the 35th anniversary of their murder in the town of Santiago Nonualco, El Salvador. (CNS/Reuters/Jose Cabezas)

People stand near an image of Fr. Stanley Rother, a priest of the Oklahoma City Archdiocese, during Mass in 2006 at a church in Santiago Atitlan, Guatemala. (CNS/Reuters/Daniel LeClair)

Edward Brett was teaching at a Christian Brothers college in 1982 when news came that soldiers had killed Christian Br. James Miller in Guatemala while he worked with Mayan Indians. In part because many of Brett's Christian Brother colleagues knew Miller well, Edward and his wife, Donna, were determined to tell Miller's story to a wider audience.

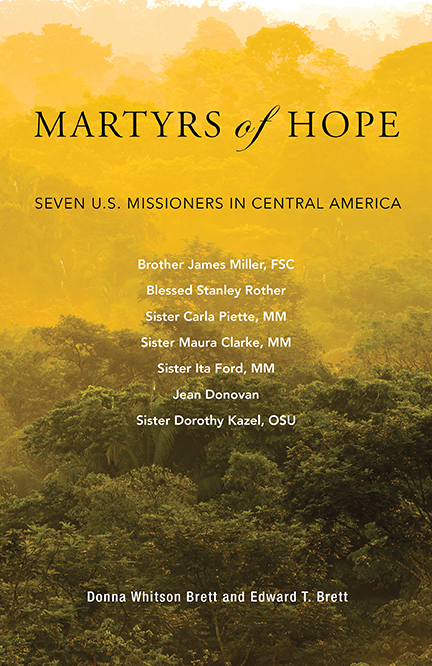

That initiative led to their 1988 book Murdered in Central America: The Stories of Eleven U.S. Missionaries. Their 2018 follow-up to that work, Martyrs of Hope: Seven U.S. Missioners in Central America, focuses also on the U.S. government's role in the bloody repression of Latin Americans aspiring to live in dignity and hope. The result is a compelling and thorough discussion of the lives and murders of seven of the original 11 martyrs, put in a rich historical context.

Reading these stories about exceptionally generous and self-sacrificing Catholics, however heartbreaking, reminds readers of the extraordinary work that made the church such a compelling force for good in the world and provides a welcome reprieve from the drumbeat of revelations about church officials' predatory efforts in this country and abroad.

The Bretts begin their book with examples of Catholic champions of indigenous rights from the early colonial period in Latin America. But the story really starts with Pope John XXIII's call in 1961 for Catholic religious orders and dioceses in the United States to send 10% of their personnel to work in Latin America. Many sent a handful of volunteer missioners south, including the seven martyrs in this book.

Fr. Stan Rother was a priest from Oklahoma City who joined a team of 10 priests, sisters and lay volunteers at the diocese's Micatokla mission in Santiago Atitlán, Guatemala, in 1968. By 1975, he was the lone North American working at the mission. Like virtually all of the other martyrs whose stories the Bretts tell, Rother was no radical. In fact, his political conservatism should have made him quite popular among the ruling elite and with the church that served their interests so attentively.

But his work among the poor and marginalized Mayan Indians inevitably put him at odds with the plantation owners who governed the economic, political and military arenas. Though Rother organized no formal challenges to the existing order, those in power perceived as threats his work training catechetical leaders among the laity, supporting education and health care initiatives, and even sponsoring efforts to translate the Gospels into the native Mayan tongue.

When word filtered to Rother that he appeared on a list of assassination targets, he took steps to avoid that fate. He left the country for a while, but then returned. He moved his bedroom within the rectory to hide from would-be assassins. These were not enough. Three men came at night on July 28, 1981, and tried to take him away. He resisted vigorously before they shot and killed him.

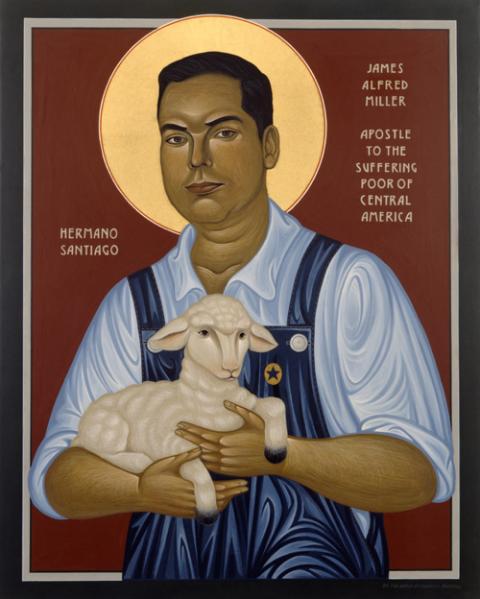

Br. James Miller, pictured in an image from the Christian Brothers of the Midwest (CNS/Courtesy Christian Brothers of the Midwest)

Miller met a similar fate in Guatemala, though he had spent most of his missionary years in Nicaragua. There, he had allied himself with the oppressive regime of Anastasio Somoza in opposition to the revolutionary forces that eventually overthrew the Somoza government. A high school teacher by training, the politically conservative Miller eventually built and ran schools in Nicaragua.

He returned to the U.S. as the Sandinistas took control and he knew that his past support of Somoza precluded his reentry into Nicaragua. Instead, he went to Guatemala to help run a school for Mayan boys. During his time there, he became increasingly aware of the social, political and economic injustices that kept the Mayans from living dignified and secure lives.

He did not crusade for political upheaval and did not embrace liberation theology. He remained a pragmatic man, more concerned with making schools run efficiently than transforming society. In fact, he was patching a wall atop a ladder when three men shot him dead in broad daylight on Feb. 13, 1982.*

The Bretts turn from Miller's biography to the stories of four religious sisters and one laywoman missioner killed in El Salvador in 1980. Maryknoll Srs. Carla Piette, Maura Clarke and Ita Ford, and Ursuline Sr. Dorothy Kazel took varying paths to El Salvador, but ended up, like lay missioner Jean Donovan, assisting refugees from the civil war raging throughout the small Central American nation.

For a long time, they considered their U.S. citizenship to be an advantage in this work, and believed that it diminished the likelihood that the Salvadoran military, funded so heavily by the United States, would target them. In the end, it was not sufficient though, as members of the Guardia kidnapped, raped and then executed four of the missioners as they drove from the airport back to their quarters in Chalatenanga. The fifth, Piette, had drowned just weeks earlier when the jeep she and Ford were driving flipped over in a swollen stream.

Though it was clear to most interested parties that the assassins acted on orders from above, neither the Salvadoran nor the U.S. governments investigated this vigorously.

As with Rother and Miller, the five women missioners came from mostly conservative and moderate political backgrounds. The most conservative of the five, Donovan, entered her mission work resistant to a critical analysis of the social conditions in Latin America. It was only after years in the region working with the poor that she came to embrace social justice fully. The sisters arrived earlier to this understanding, but only after they, too, witnessed the widespread and debilitating oppression of those Catholics with whom they labored.

The Bretts develop this important point because many critics of the murdered missioners, including even high-ranking members of the Reagan foreign policy team, argued that the victims promoted armed resistance to the government and fomented revolution — that they helped to radicalize an otherwise contented population. The Bretts argue convincingly that the missioners supported only the revolution of Christian love of neighbor, and that this was sufficient for state authorities to see them as dire threats.

The church beatified Rother in 2017 and will beatify Miller in December. Not so the five women who also gave their lives. Readers may reasonably wonder why, and the authors provide ample evidence in their enthralling narrative upon which to move that cause forward.

*This story has been updated to correct the year that Miller was killed.

[Timothy Kelly is a professor of history at St. Vincent College in Latrobe, Pennsylvania.]

Advertisement