A sculpture of the Crucifixion at Regis University in Denver (Dreamstime/Rsheya)

Editor's note: The following is an excerpt from The Crucible of Racism: Ignatian Spirituality and the Power of Hope (Orbis Books) by Patrick Saint-Jean, SJ.

The Suffering of the Black Community

The second way we can enter into a deeper relationship with Jesus during this stage of The Spiritual Exercises is by relating Christ's suffering to the pain we see in the world around us. Instead of retreating into a life of comfort and privilege, we allow the suffering of others to become real to us. "Everything," wrote Ignatius, "has the potential of calling forth in us a deeper response to our life in God." As we take this to heart, we do not turn away from the reality of injustice in our world.

We consciously choose to dethrone our egos from their place of authority in our lives — and, like Jesus, we "empty" ourselves; we stop grasping at our need to be important, to be better than others, to be free from discomfort. "Our only desire and one choice," wrote Ignatius, "should be this: I want and choose what better leads to God's deepening life in me."

As we make this choice, we begin to see Jesus in the suffering of people of color. "God's presence in the world is best depicted through God's involvement in the struggle for justice," says religion professor Anthony Pinn. "God is so intimately connected to the community that suffers, that God becomes a part of that community."

Charlotte, North Carolina, 2020 (Unsplash/Clay Banks)

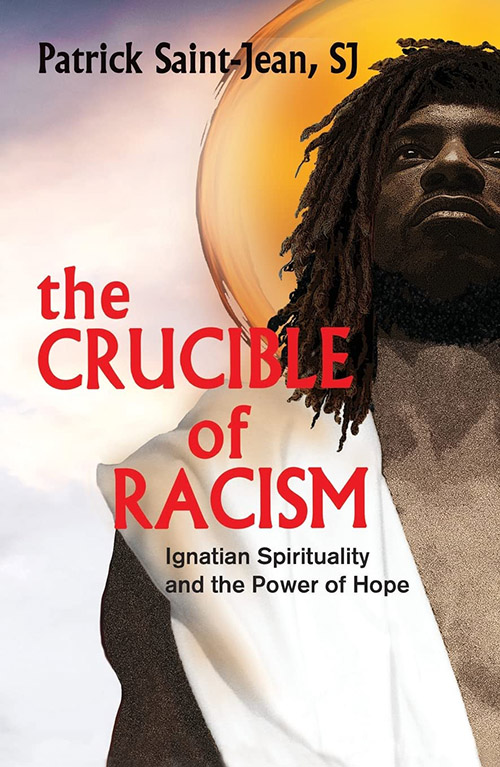

As we become aware of the Divine Presence within the suffering of the Black community, we are challenged to affirm, "Black lives matter." And yet I have had friends counter this statement with the response that "all lives matter." Of course all lives matter; that should be a self-evident fact. But for centuries, Western society has been built around the assumption of white supremacy. We do not need to assert that "white lives matter," because no one has ever contradicted that fact.

This is not to say that white people haven't suffered, particularly those who are poor, female, or at the margins of society in some other way; but they did not suffer simply because of the color of their skin in the way that Blacks and other people of color have suffered. For centuries, Blacks have had to face the constant struggle to assert that their lives do matter, equally as much as that of any white person.

The story of suffering is a long one. Historians often date the beginnings of racism to 1619, when a ship carrying captive Africans landed in a Virginia port. From this moment on, Black bodies were unfree bodies. They were not considered to be human in the same way that white people were.

But slavery and racism actually began even earlier than 1619. In the mid-fifteenth century, the treatment of "black Gentiles" was first addressed when Pope Nicholas V issued a series of edicts that granted Portugal the right to enslave sub-Saharan Africans. Church leaders insisted that slavery would Christianize the Africans' "barbarous" behavior, and so the Pope issued a mandate to the Portuguese king, Alfonso V, giving him the right "to invade, search out, capture, vanquish, and subdue" the inhabitants of Africa and "reduce their persons to perpetual slavery."

Elmina Castle, in present-day Ghana, was built by the Portuguese in the 15th century as Castelo de São Jorge da Mina and used for slave trade during the colonial era. (Wikimedia Commons/Adam Tuferu)

Although the Church at first limited African slave trading to Portugal, other European nations soon followed. The Netherlands, France, England, Portugal, Spain, Norway, and Denmark all participated. The supremacy of the white body over Black bodies became a useful concept, an economically advantageous idea that allowed white men to grow rich. The world's growing capitalist economies were rooted in slavery, giving birth to the systemic racism that now spreads throughout so many social and economic structures.

As author Resmaa Menakem noted, racism grew up in North America, where "there is this shorthand that exists in the soil that says that [whites are] more human than [Blacks]." But then that belief was also exported back from the colonies to the parent countries. "So the progeny of the idea of the white body being the supreme standard has utility even in the parental countries." These parent nations then carried the warped standard of white supremacy to all their colonies: to South Africa, to India, to Australia, and to other regions throughout the world.

Today, Blacks and other people of color around the globe continue to suffer twenty-first-century versions of slavery's suffering. Poverty, police brutality, mass incarceration, hate crimes, and unequal educational and professional opportunities are all aspects of that suffering. The second phase of The Spiritual Exercises calls us to open our eyes to these realities — and see Jesus present in the pain of the Black community.

The Biblical Call to Justice

White Christianity has much to learn from the Black church. Five words have defined Black theology ever since the days of slavery: justice, liberation, hope, love, and suffering. The Bible echoes these same themes, and yet white Christianity has overlooked the calls for justice that are everywhere in both the Hebrew and Christian scriptures:

The Lord has anointed me; he has sent me to bring good news to the oppressed, to bind up the brokenhearted, to proclaim liberty to the captives. ... For I the Lord love justice. [Isaiah 61:1, 8]

"How long will you judge unjustly and show partiality to the wicked? Give justice to the weak and the orphan; maintain the right of the lowly and the destitute. Rescue the weak and the needy; deliver them from the hand of the wicked." [Psalm 82:2-4]

"Woe to you, scribes and Pharisees, hypocrites! For you ... have neglected the weightier matters of the law: justice and mercy and faith." [Matthew 23:23]

A mural of Jesus at the Way Jesus Christ Christian Church in New Orleans (Flickr/Bernard Spragg)

These verses related to justice are only a few of many, many more found in the Bible. And yet somehow white Christians have found ways to ignore these verses that are at the heart of their sacred scripture. Meanwhile, the Black church has read them and found a God who is on their side, a God who identifies with their suffering — a God who is with them. In the stories of the Hebrew slaves' exodus into freedom and Christ's suffering at the hands of his oppressors, Blacks found a God who no longer wore a white man's face.

The Black Jesus

This is not an intellectual theology but one that has been lived and felt, one that has been physically experienced. It has empowered the Black community with hope. It has allowed them to look past the image of the blond-haired, blue-eyed Christ that was portrayed in so many white churches and see a Black Jesus — a Jesus who not only spoke out for the oppressed but who also experienced firsthand the suffering of an unjust system.

When we come into relationship with the Black Jesus, a man who was persecuted by the authorities, it is more than an intellectual exercise. Through the Ignatian concept of imaginative prayer, we identify with the suffering of Jesus within the Black community, and in doing so, we enter into a deeper intimacy with Christ.

Writing on a car window supports Black Lives Matter in 2016 in a parking lot at a Donnelly College, a Catholic institution in Kansas City, Kansas. (NCR photo/Toni-Ann Ortiz)

And then we are challenged to go a step further. As we meet the Black Christ in others, we can no longer think of ourselves as "innocent bystanders" to the reality of racism. Once we allow ourselves to be truly present to the suffering of the Black community, we are called to take action. Christ calls us to embody his call for justice within our own lives. As theologian James Cone wrote:

There can be no reconciliation with God unless the hungry are fed, the sick are healed, and justice is given to the poor. The justified person is at once the sanctified person, one who knows that his or her freedom is inseparable from the liberation of the weak and the helpless.

The work of justice requires a wholehearted, active, and positive commitment to antiracism. There is no sitting on the fence, no neutral territory. Ibram Kendi pointed out, "One either allows racial inequities to persevere, as a racist, or confronts racial inequities, as an antiracist. ... The claim of 'not racist' neutrality is a mask for racism." This takes courage and a dedication to hearing the experience of others, while uncovering our own complicity with racism. It requires the humility to hear the stories of those who have been marginalized and excluded. Through the lens of Ignatian spirituality, we see God in others and at the same time we allow divine love to move through us.

The acknowledgment of the Divine Presence within the suffering of the Black community is not easy. It is not comfortable or pretty. And, as James Cone acknowledged, the reality of suffering can make us doubt the love of God. "How can one believe in God in the face of such horrendous suffering as slavery, segregation, and the lynching tree?" Cone asked. But then he affirms: "Under these circumstances, doubt is not a denial but an integral part of faith. It keeps faith from being sure of itself. But doubt does not have the final word. The final word is faith giving rise to hope."

Advertisement

Trust and Possibility

This brings us back to the importance of trust in both our relationship with Christ and in the work of antiracism. As the first "week" of The Spiritual Exercises stressed, God endlessly loves us and gives us life. "Our own response of love allows God's life to flow into us without limit," wrote Ignatius. As my friend and I discovered on our long road trip, trust is what makes intimate relationship possible. It is what makes hope possible.

My Jesuit brother Greg Boyle has demonstrated the miracles that trust can achieve. In 1986, Father Boyle began Homeboy Industries as a ministry of trust and hope. At the time, violent police tactics and mass incarceration were considered the best way to deal with gang violence. But where others only saw criminals — many of them people of color — Father Boyle saw the face of Christ. He saw possibility.

His audacious trust in those who were considered to be untrustworthy looked like insanity. Even many of his fellow Jesuits thought so. Today, though, Homeboy Industries is the largest gang intervention and rehabilitation program in the world. "Homeboy Industries," says Father Boyle, "has chosen to stand with the 'demonized' so that the demonizing will stop; it stands with the 'disposable' so that the day will come when we stop throwing people away."

Racial healing requires trust. And this trust must be mutual. Even as we extend trust to others, we must be careful to be trustworthy ourselves. This atmosphere of trust is what Father Boyle has created through his work.

Members of a gospel choir named for Franciscan Sr. Thea Bowman, a Black American candidate for sainthood, sing during a Black History Month Mass of thanksgiving at Immaculate Conception Church in Queens, New York, Feb. 20. (CNS/Gregory A. Shemitz)

As a Black man, I have found that Ignatian spirituality prescribes trust as a spiritual medicine for the suffering of racism, even at the level of microaggression fatigue. Trust allows me to experience gratitude and forgiveness. I am not, of course, grateful for being exposed to a constant onslaught of microaggressions — but with awareness of the Divine Presence in each moment, I can be grateful that I have this opportunity to identify more fully with Jesus. I can allow the Breath of Life to move through me, rather than blocking its flow with resentment, defensiveness, or fear. I let go of the resistance that keeps me from inviting a broader perspective into my experience, and in doing so, I recognize that I live within a spiritual reality. My experience in this world is temporary, but God's love is eternal. With this knowledge, I have a renewed sense of peace, freedom to breathe, and hope. I can pray with Ignatius:

Jesus, may all that is you flow into me. May your body and blood be my food and drink. May your passion and death be my strength and life. Jesus, with you by my side enough has been given. May the shelter I seek be the shadow of your cross. Let me not run from the love which you offer, but hold me safe from the forces of evil. On each of my dyings shed your light and your love. Keep calling to me until that day comes, when with your saints, I may praise you forever. Amen.

This second week of contemplation comes as a treasure and a challenge. It requires our constant attention to social injustice. It shines brightly during the Age of Breath, allowing us to meet Christ in the suffering of people of color. The powers of our imagination can inspire us to actively work toward peace and reconciliation.

The grace we seek during the second phase of The Spiritual Exercises is captured in a prayer that Ignatius included in The Spiritual Exercises, one that is often repeated by Jesuits: "Lord, grant that I may see thee more clearly, love thee more dearly, and follow thee more nearly." As we enter into this deeper, more intimate relationship of trust, we turn away from racial superiority, from greed and pride, and instead, we consciously choose to align ourselves with the spiritual poverty, self-emptying, and humility that leads to racial equity. We step away from fear and defensiveness, and we enter into new intimacy with both God and others. As we meet Christ in one another, we are empowered to risk going beyond our limitations. We become people of possibility.

[Content taken from The Crucible of Racism by Patrick Saint-Jean, SJ, ©2022. Used by permission of Orbis Books.]