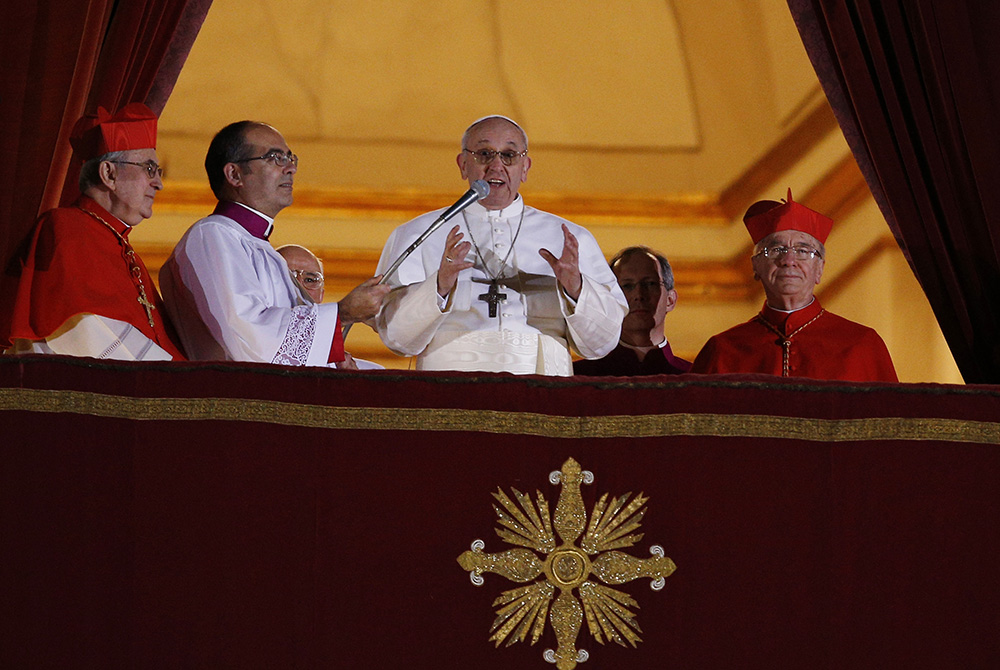

Pope Francis addresses the world for the first time from the central balcony of St. Peter's Basilica at the Vatican March 13, 2013. (CNS/Paul Haring)

It turns out that the very secret conclave that elects the pope is not that secret after all. If you have ever dreamed of being the proverbial fly on the wall during the election of a pope, then Gerard O'Connell's The Election of Pope Francis: An Inside Account of the Conclave that Changed History might make your dream come true. In spite of numerous oaths of secrecy taken by the cardinal electors before and during the conclave, O'Connell delivers a surprisingly detailed report on the highly charged drama that unfolded in the days just before and during election of Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio as bishop of Rome and supreme pontiff of the Catholic Church.

O'Connell knows the territory. He has covered the Vatican since 1985 for a number of English-speaking publications, including the National Catholic Reporter, and was the lead analyst and reporter for CTV, Canada's No. 1 television network, for the 2013 conclave that elected Francis. Moreover, he and his wife, Elisabetta Piqué, a journalist from Argentina, are longtime personal friends of the pope. Such good friends that, the day after the election, Francis personally called each of them. Their family dinners with Bergoglio gave both journalists a leg up on their media colleagues covering the conclave.

Written in the genre of a journal, The Election of Pope Francis is divided into four parts: Part I follows the developments from the announcement of Pope Benedict XVI's resignation on Monday, Feb. 11 to its effective date on Thursday, Feb. 28, 2013, and the media frenzy that followed.

Part II covers the first 11 days of March 2013, when the "See of St. Peter is Vacant." It is here that the scarlet-robed princes play high-stake politics. During this period, the College of Cardinals, including the non-electors over the age of 80, are called to the Vatican for a series of caucuses called the general congregations. These formal meetings, preceded by oaths of secrecy, give each cardinal an opportunity to speak to the entire college about their understanding of the state of the church and the challenges facing the new pope. These ecclesial "back room" meetings — without cigars and brandy — have significant force in shaping the minds of the cardinal electors. In spite of the oaths of secrecy, O'Connell reports adeptly the shift and drift of support for the acknowledged frontrunners, Cardinals Angelo Scola, Odilo Scherer, and Marc Ouellet. (In O'Connell's journal entry for the day of election, March 13, 2013, he notes that "Bookmakers are having a field day with the conclave and hope to make big money." The latest odds for three of the candidates reported by the Italian paper La Repubblica were: Scola, 3.25/1; Scherer, 4.5/1; and Bergoglio, 41/1.)

But the formal caucuses were matched in influence by the informal lunches, dinners and private parties hosted by influential cardinals representing various ecclesial perspectives and specific candidates. Not only does O'Connell tell his readers the names of the cardinals who attended these events, but often what was said. What emerges is a quite human drama of high church politics. But always, it would seem, after sincere prayer by the cardinals for direction by the Holy Spirit.

Part III covers the conclave itself. Here O'Connell reports the specific number of votes for each cardinal candidate on four of the conclave's six ballots. On the final ballot, Bergoglio garnered 85 votes (77 marked the two-thirds needed for election by the 115 cardinal electors), Scola 20, Ouellet 8, and Cardinal Agostino Vallini 2. The cardinals clapped when Bergoglio reached 77 votes and applauded again when the final tally was announced. Immediately after the applause, O'Connell notes, "Cardinal Bergoglio got up and went to Cardinal Scola … and embraced him." Francis' second call to his predecessor, Benedict XVI, got through. The pope emeritus was overheard saying, "I thank you Holy Father that you have thought immediately of me."

White smoke billows from the chimney of the Sistine Chapel March 13, 2013, at the Vatican. (CNS/Paul Haring)

Part IV reports on the first six days of Francis' pontificate, titled "Early Signs of a New Style of Papacy": it captures with often moving anecdotes the new style of the first Latin American, the first Jesuit, and first pope ever to choose the name Francis. The following morning, Thursday, March 14, the new pope, driven now in a dark colored Ford Focus, returned to his pre-conclave hotel, the Domus Paulus VI, to pay his bill. Bergoglio often stayed at the Domus when in Rome, and O'Connell learned from one of its staff members who knew the cardinal well that he never wanted to be served. "He is a saint," she said, and went on to say of the many priests and prelates who stayed at the hotel, Bergoglio was the only one who always made his bed.

Hours later, Francis made a call to Daniele, the proprietor of the newsstand in the Plaza de Mayo in Buenos Aires, who faithfully delivered each day to Padre Jorge the newspaper, La Nacion. "Francis thanked him for his service all these years and asked him to cancel his order. Daniele was incredulous at first, but when he realized it was for real, he broke into tears."

O'Connell's journal format works well, especially in Parts III and IV, which I found informative and even spellbinding. He certainly delivers. Yet the greatest takeaway for me came from between the lines. The Election of Pope Francis unveils the readiness of the church's highest-ranking prelates to wink at their solemn oaths of secrecy surrounding the pre-conclave caucuses and the conclave itself. All of the cardinals, not only the electors, swore "to observe exactly and faithfully" all the norms governing a papal conclave and "to maintain rigorous secrecy" regarding all matters relating to the conclave. Moreover, these oaths are bound under pain of excommunication reserved to the Holy See. Many older Catholics, I believe, would understand that the breaking of such oaths would constitute a mortal sin. Strangely, this dire sanction seems not to have mattered at all — even to the new pope.

Advertisement

On March 16, 2013, three days after his election, Francis met with more than 6,000 media personnel who had covered the conclave. O'Connell writes that after warm and engaging off the cuff remarks, "Francis surprised and delighted journalists by revealing some of the secrets of the conclave, and giving them the news story of the day."

Could it be that O'Connell's book unwittingly is a window into the collapsing moral credibility of the Roman Catholic Church?

[Fr. Donald Cozzens, a former seminary rector, served as writer in residence at John Carroll University from 2002 to 2015. He is the author of the award-winning The Changing Face of the Priesthood. His latest books are novels: Master of Ceremonies and Under Pain of Mortal Sin.]