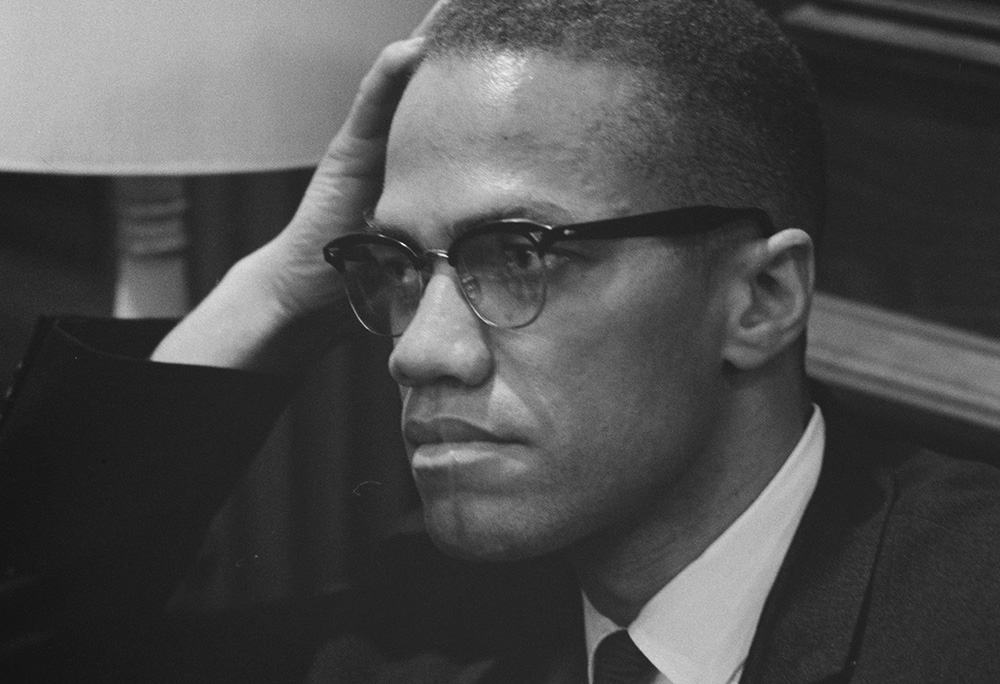

"I had entered Bushnell Hall as a Negro with a capital N and I wandered out in the parking lot as a black man," late African American journalist Les Payne wrote in his 2002 essay "The Night I Stopped Being A Negro." The Pulitzer Prize-winning Newsday investigative reporter was one of 60 African American students present when Malcolm X spoke to the University of Connecticut in June 1963.

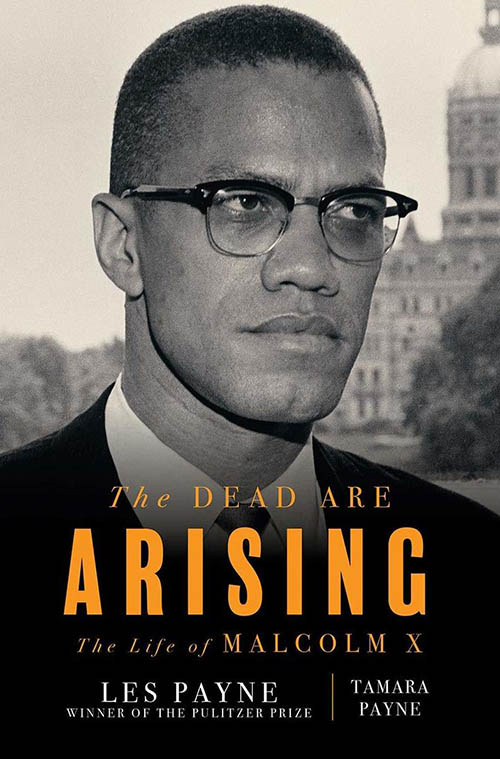

This story — and many others — is described in the latest biography on the Black icon, The Dead Are Arising: The Life of Malcolm X.

After Payne's death from a heart attack on March 19, 2018, at 76, his daughter and principal researcher Tamara finished her dad's labor of love. Thirty years in the making and deeply sourced, the biography adds to our understanding of one of the 20th century's more consequential leaders.

Culling the apocryphal from reality in Malcolm's record, the journalists refute Malcolm's contention that the Black Legion, a Ku Klux Klan offshoot, killed his father, Earl. In actuality, he died Sept. 28, 1931, when he fell under a Lansing, Michigan, streetcar, which crushed him.

After his father's death and following his mother's institutionalization, Malcolm and his siblings lived in foster homes until he eventually moved to New York City and Boston in the early 1940s. There, he engaged in illegal activities that ultimately landed him in jail. On Feb. 27, 1946, Malcolm was arrested in Boston for robbery and sentenced to 10 years in Massachusetts' Charlestown State Prison. He was 20.

His family introduced the inmate to the Nation of Islam. Sect leader the Honorable Elijah Muhammad taught the future minister that "the black man was the 'original man,' and had 'built great empires and civilizations and cultures while the white man was still living on all fours in caves.' "

Paroled in August 1952, the 26-year-old soon became adept at "fishing" for new Nation of Islam recruits. As the title suggests, the dead were rising to a new life with the Nation of Islam because of him. But, the Paynes write, "his masterly facility with words contrasted sharply with the limitations of his mystic leader."

Advertisement

"The Honorable Elijah Muhammad teaches us," Malcolm vigilantly couched his public commentary on Nation of Islam's behalf, but the gifted orator became identified, in the public's perception, as its spokesperson.

A split between the two men became ineluctable. Views about what happened traditionally emphasize Malcolm's concerns about Muhammad's serial adultery with multiple secretaries. Malcolm's legendary "the chickens coming home to roost" response to President John F. Kennedy's November 22, 1963, assassination also warranted him a 90-day suspension from the Nation of Islam before his March 1964 complete break from it.

The authors' new theory will likely engender controversy: Malcolm planned to expose the Nation of Islam's affiliation with the Klan, initiated by the Georgia Klan's 1960 invitation for the groups to meet clandestinely. Muhammad, who preached all whites are "blue-eyed devils," nonetheless believed both groups opposition to integration and race mixing was conducive to their meeting.

Muhammad and Malcolm met on Jan. 28, 1961, at local minister Jeremiah X's Atlanta home. The Klan tried to exploit the groups' perceived common hostility toward the Jews and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. to forge an unlikely partnership to stop integration.

"But anti-Jewish sentiment was not a feature of Nation of Islam policy," the Paynes write. And the suggestion the Nation of Islam spy on King "left Malcolm reeling."

Muhammad's "overture to the Klan," the authors say, was "a major turning point in the relationship between the two strong men."

Readers familiar with this history will appreciate the writers' freshly illuminating Malcolm's narrative, and those new to Malcolm's history will appreciate the authors' expertise.

Martin Luther King Jr. speaks to Malcolm X as they wait for a press conference on Capitol Hill, Washington, D.C., March 26, 1964. (Library of Congress/U.S. News & World Report Magazine Photograph Collection/Marion S. Trikosko)

Nonetheless, the 2020 National Book Award recipient's analysis could have gone deeper.

The authors' failure to discuss Malcolm's fabled "The Ballot or the Bullet" speech is an egregious and mystifying omission. Regarded as one of U.S. history's more impactful addresses and delivered at Cleveland's Cory United Methodist Church on April 3, 1964, it articulates the Black Nationalist leader's core philosophy.

"The Black Nationalist freedom fighter" urged his audience to control their communities' politics and economy. The minister prescribed the revolution would be "bloodless if you give the Black man everything that's due to him."

This revolution would come about "by any means necessary," Malcolm said at Harlem's Audubon Ballroom on June 28, 1964. On that date, he announced the Organization of Afro-American Unity's formation, which sought to unite the then 22 million Black Americans with people of African descent worldwide in a struggle to achieve their freedom. "Don't teach us nonviolence while those crackers are violent. Those days are over," Malcolm said.

Those who believe that racial justice must be nonviolent must grapple with the minister's stance toward violence and his still evolving racial attitudes.

As Malik El-Shabbaz and a Sunni Muslim, Malcolm famously made a hajj to Mecca in April 1964. There, he encountered people with blonde hair, blue eyes and white skin. But he insisted God removed the "white" from their minds, behavior and attitude.

Malcolm was only 39 when Nation of Islam members assassinated him on Feb. 21, 1965, at the Audubon, and we don't know how he would have resolved the internal conflict between his religious beliefs and political attitudes. As readers contemplate this freedom fighter's legacy, his changing thinking on race may reassure some. But, as Les Payne wrote in a 1989 Newsday column, Malcolm finally was a "revolutionary," who "upset the white man's grossly inflated sense of himself" while urging Blacks to reject "the way" whites "looked down upon blacks as inferiors." Malcolm's prejudice was regrettable and his embrace of violence should be rejected, but he's deservedly remembered for tenaciously fighting to free his people.

Despite its shortcomings, The Dead Are Arising: The Life of Malcolm X welcomingly fills out the portrait of this liberator who still provokes us to pursue racial justice.