A child lines up to receive free back-to-school supplies in Los Angeles in 2016. (CNS/Reuters/Lucy Nicholson)

In 1962, Michael Harrington, an alumnus of the Catholic Worker, published The Other America: Poverty in the United States. A bestseller, the book influenced the social welfare policies of President John F. Kennedy, his brother Sen. Robert Kennedy and President Lyndon Baines Johnson. Johnson's "War on Poverty" could be considered the culmination of their efforts to establish programs to help the American poor.

But according to Jeff Madrick, an economist and New York Times op-ed writer, in today's America social welfare programs have been watered down, and poverty is even worse now than it was in the 1960s. Poor people, especially children, pay the price.

His latest book, Invisible Americans: The Tragic Cost of Child Poverty, hopes to call attention to the plight of poor families and offer ways to ameliorate their problems, which range from a lack of nourishing food to a lack of adequate housing to a lack of health care.

The statistics are grim. Recent studies estimate that children make up "roughly one-quarter of the population but one-third of the official poor." Homeless families with children are 33% of the homeless. In today's America, 2.5 million children will be homeless some part of this year.

"The sheer number of poor children," Madrick writes, "is a moral tragedy and an appalling waste of precious resources." No other First World country treats its children this way.

Proposing ways to lower the rate of child poverty, Madrick suggests giving all families cash for their children — rich and poor. The rich families will pay the money back in taxes; the poor families will keep the money for basic necessities. He approves of the proposal by Sens. Michael Bennet and Sherrod Brown for allowances of $3,000 per year per child for children between 6 and 18, and $3,600 per year for children under 6, although Madrick would increase the amount to between $4,000 and $5,000.

Well-researched, the book outlines the problems of poverty, considers its history in the United States as well as efforts (and the lack thereof) to reduce poverty. The book is heavy with statistics and includes numerous graphs and 53 pages of notes — all of which makes it a slow read.

The exception is a chapter in which Madrick draws on several examples of poor families and children, which adds human interest. But these quick sketches never capture the individuals who suffer through poverty the way that The Other America did.

As Harrington wisely put it, the poor need an "American Dickens to record the 'smell and texture' of their lives."

Advertisement

Celibate may be a catchy title, but it doesn't adequately encompass the territory of Maria Giura's memoir.

A devout, Roman Catholic woman, Giura tries to find herself but is waylaid by a womanizing parish priest, Fr. James Infanzi, who takes advantage of women coming to him for advice — often advice concerning marital difficulties — and uses the occasion to seduce them. The women feel special, honored by this attention, which they believe is offered to no other woman.

Blinded by the pseudo sheen of clericalism, Giura cannot remove her blinders — even after she saw him flirting with other women and after another priest told her that Infanzi would only love her until the next attractive woman came along.

Giura roughly divides her book into two parts, the first covering her infatuation with a handsome priest just a few years older than she is. The second focuses on her gradually doubting the sincerity of Infanzi's affection.

Maria Giura (Danny Sanchez)

About halfway into her narrative, Giura alludes to the Bill Clinton and Monica Lewinsky affair, but doesn't see that their story resembles her own. She doesn't realize that her priest paramour is a man who takes advantage of the reverence that Catholics bestow on their religious and that he exemplifies clericalism at its worst.

Into the mix, Giura weaves her family's worries about her friendship with Infanzi and her own fascination with religious life, which becomes the memoir's subtheme. She decides she'd like to join the Sisters of Charity — the order founded by St. Elizabeth Ann Seton — because they don't pray all that much, and they work in the world, a reason that seems antithetical to religious life.

Giura's attraction to men and her desire to marry and bear children further muddies her life and the narrative. She tends to be a mystic and ignore her own natural tendencies, preferring instead to search for signs God as to what God might want from her.

Ultimately, this is a #MeToo story with heavy dollops of Catholic piety. Giura protects her priest boyfriend and sees their affair (even after it seems to be over) as mainly her fault, making her intriguing narrative a frustrating read.

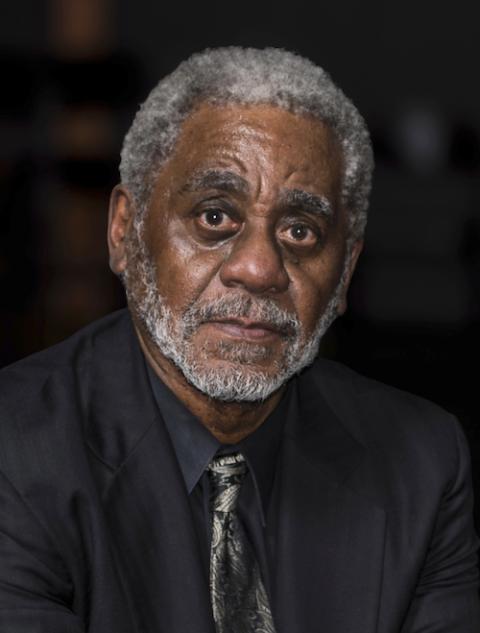

Proclaiming that people are processes, not products, Charles Johnson says that today's college graduate will change jobs five times or more. Johnson should know. The author of 23 books, he's had more than a few callings in his 71 years — as a writer, cartoonist, artist, philosopher, professor, Buddhist, martial artist, journalist, novelist and winner of the National Book Award for The Middle Passage, his novel about slavery and its effects.

Johnson is also a grandfather of Emery, his 6-year-old grandson. It's as a doting grandfather that Johnson writes in Grand.

Although the subtitle suggests otherwise, this book isn't written to Emery but written about thoughts that his grandfather would like to share with him. It fuses Johnson's personal memories with anecdotes he's heard, advice people have shared with him, and ideas he's found in his studies which, as one can imagine in a person of Johnson's stature, are wide-ranging.

Charles Johnson (Crystal Riley-Brown)

This rambling and warmly written memoir, covers widely, including Aristotle's advice that the unexamined life is not worth living; Martin Luther King's favorite Bible story in Matthew 4, where Jesus calls the disciples; and Guy Murchie's assertion (which seems a stretch) that "all of us cannot be more distantly related than fiftieth cousins."

There's a chapter on logical fallacies with a side note that only two kids out of 80 take logic courses in college. There's even a section on studying the Sanskrit language, also with side notes such as: The word Sanskrit means "language brought to formal perfection." And NASA discovered that "Sanskrit is the only unambiguous language on earth."

The most memorable chapters, though, concern Johnson's family and his own recollections. There's his father, a workaholic who refused to work on a Sunday because "Sunday is for church." And there's great Uncle Will, one of the most hardworking and inventive members of the family. He started out as the son of a farmer, but worked his way up by recognizing a need then answering it.

Emery probably won't appreciate this book until he's in college. But that's okay. There's enough fascinating grist for the mill to engage almost anyone.

[Diane Scharper is the author of seven books. She teaches memoir and poetry for the Johns Hopkins Osher Program.]

Editor's note: Love books? Sign up for NCR's Book Club list and we'll email you new book reviews every week.