Pope Francis waves from his car after celebrating Mass and signing his new encyclical, "Fratelli Tutti, on Fraternity and Social Friendship" at the Basilica of St. Francis Oct. 3 in Assisi, Italy. (CNS/Paul Haring)

Any attempt to read Pope Francis' new encyclical Fratelli Tutti solely through an American lens is bound to result in a distortion of the document. The pope is the universal pastor of the Catholic Church and this text is available to all, even to non-Christians. And, while it began as a reflection on interreligious dialogue, the pope makes clear that the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic took the text in a different direction, a direction that also makes all parochial readings inadequate.

That said, the document is not the least bit abstract; it is meant to be applied. And, in the event, the moral and anthropological lessons the Holy Father draws in this reflection could scarcely be more relevant to the unique circumstances of the Catholic Church in the United States as it faces next month's two election cycles: The election of a president by the nation on Nov. 3 and the selection of new leadership at the U.S. bishops' conference the following week.

A word about the document's structure. As in his first encyclical "Laudato Si', on Care for Our Common Home," Pope Francis here follows the "see, judge, act" methodology originated by Cardinal Joseph Cardijn of Belgium. The first third of the document entails a survey of the contemporary situation in which humankind finds itself.

I confess I still find this approach a bit jarring. There are plenty of quotes from earlier statements by Francis, as well as citations to Pope Benedict XVI's wonderful encyclical Caritas in Veritate. But the theological observations are like grace notes in a musical score in this section. The essence of the melody is descriptive and pastoral, not didactic and theological.

So, for example, we read this observation about the international response to the pandemic:

For all our hyper-connectivity, we witnessed a fragmentation that made it more difficult to resolve problems that affect us all. Anyone who thinks that the only lesson to be learned was the need to improve what we were already doing, or to refine existing systems and regulations, is denying reality (Paragraph 7).

It is pithy and true, but it does not sound like the kind of magisterial text to which we are accustomed.

Or, consider these comments about the post-war consensus on the need for regimes inspired by Christian democracy and built on solidarity and freedom, and the unravelling of that consensus in our own time:

For decades, it seemed that the world had learned a lesson from its many wars and disasters, and was slowly moving towards various forms of integration. For example, there was the dream of a united Europe, capable of acknowledging its shared roots and rejoicing in its rich diversity (Paragraph 10). …

Our own days, however, seem to be showing signs of a certain regression. Ancient conflicts thought long buried are breaking out anew, while instances of a myopic, extremist, resentful and aggressive nationalism are on the rise. In some countries, a concept of popular and national unity influenced by various ideologies is creating new forms of selfishness and a loss of the social sense under the guise of defending national interests (Paragraph 11). …

One effective way to weaken historical consciousness, critical thinking, the struggle for justice and the processes of integration is to empty great words of their meaning or to manipulate them. Nowadays, what do certain words like democracy, freedom, justice or unity really mean? They have been bent and shaped to serve as tools for domination, as meaningless tags that can be used to justify any action (Paragraph 14).

The style is more homiletic than magisterial, but the insights demonstrate the keen eye of a pastor who has been immersed in the work of helping the people of God navigate the complexities of their times. In this case, while the lesson is more obviously applicable to the situation of the European Union, the note about "new forms of selfishness" is an apt description of the laissez-faire economic ideology of Reaganism that has so shaped U.S. domestic policy for the past 40 years.

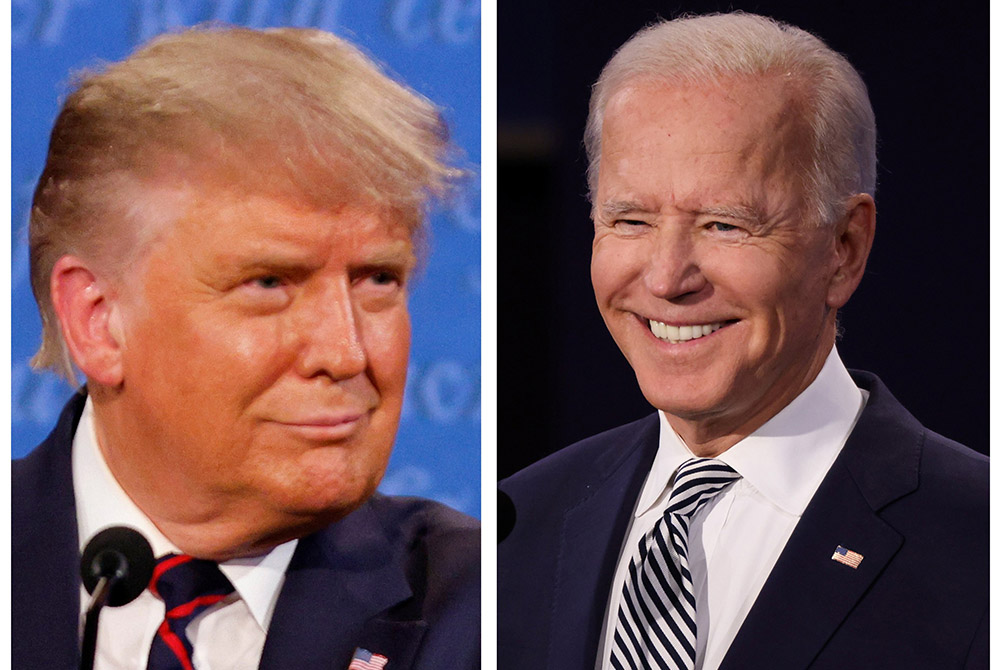

When Francis writes, "Employing a strategy of ridicule, suspicion and relentless criticism, in a variety of ways one denies the right of others to exist or to have an opinion. … In this craven exchange of charges and counter-charges, debate degenerates into a permanent state of disagreement and confrontation" (Paragraph 15), I wondered if he had received a premonition about last's week presidential debate between President Donald Trump and former Vice President Joe Biden!

President Donald Trump and former Vice President Joe Biden, the Democratic nominee for president, are seen in this composite photo. (CNS composite/photos by Jonathan Ernst and Brian Snyder, Reuters)

Other comments ring true but, again, have the feel of a sermon rather than a teaching document. "Digital connectivity is not enough to build bridges," Francis writes at Paragraph 43. "It is not capable of uniting humanity." And, in the next paragraph, he observes that, "Even as individuals maintain their comfortable consumerist isolation, they can choose a form of constant and febrile bonding that encourages remarkable hostility, insults, abuse, defamation and verbal violence destructive of others, and this with a lack of restraint that could not exist in physical contact without tearing us all apart. Social aggression has found unparalleled room for expansion through computers and mobile devices."

He deals with migrants and their plight as well as an odd section on national self-esteem. He addresses some of the ecological concerns he raised in Laudato Si'. But, the most recurring theme of this "see" part of this document is the reiteration of the traditional concerns of Catholic social teaching with the influence of market ideology.

Pope Francis concludes his survey of the contemporary socio-politico-cultural landscape, conscious that it is a "downer," with some words of hope: "Despite these dark clouds, which may not be ignored, I would like in the following pages to take up and discuss many new paths of hope. For God continues to sow abundant seeds of goodness in our human family" (Paragraph 54).

The pope then begins an exquisite reflection on the parable of the good Samaritan that serves as a key pivot to deeper theological reflection as well as to the "judge" part of the document. If you only read one section of the text, read this beautiful reflection. None of us can reflect on these questions Francis poses without a sense of shame:

Which of these persons [in the parable] do you identify with? This question, blunt as it is, is direct and incisive. Which of these characters do you resemble? We need to acknowledge that we are constantly tempted to ignore others, especially the weak. Let us admit that, for all the progress we have made, we are still "illiterate" when it comes to accompanying, caring for and supporting the most frail and vulnerable members of our developed societies. We have become accustomed to looking the other way, passing by, ignoring situations until they affect us directly (Paragraph 64).

Note the adjective "developed" in that passage. Francis is aware that, as he puts it, "The decision to include or exclude those lying wounded along the roadside can serve as a criterion for judging every economic, political, social and religious project" (Paragraph 69).

Detail of engraving "The Good Samaritan (St. Luke, Ch. 10, ver. 30)" by Jean Marie Delattre, engraved by Simon Francis Ravenet, published by John Boydell, Feb. 24, 1772 (Metropolitan Museum of Art, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1932)

I should like to jump ahead and focus on the fifth chapter titled "A Better Kind of Politics." The pope states, "Lack of concern for the vulnerable can hide behind a populism that exploits them demagogically for its own purposes, or a liberalism that serves the economic interests of the powerful" (Paragraph 155). And, a little later on, he states that:

[A popular government] can degenerate into an unhealthy "populism" when individuals are able to exploit politically a people's culture, under whatever ideological banner, for their own personal advantage or continuing grip on power. Or when, at other times, they seek popularity by appealing to the basest and most selfish inclinations of certain sectors of the population. This becomes all the more serious when, whether in cruder or more subtle forms, it leads to the usurpation of institutions and laws (Paragraph 159).

Far be it from me to suggest that the pope had President Trump in mind when he wrote those words. It might have been Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban or Italian politician Matteo Salvini. What is not really a matter for conjecture is that the pope is here condemning the nationalistic, and sometimes racist, populism they espouse.

Pope Francis' critique of market economics in this chapter really shuts the door on the attempt of neoconservatives like George Weigel and the late Michael Novak to open Catholic social teaching to a greater valuation of free market ideas. Regarding those who seek to embrace a more full-blown libertarian economic theory, the door is not only shut, but it is boarded up with Gospel truth:

The marketplace, by itself, cannot resolve every problem, however much we are asked to believe this dogma of neoliberal faith. Whatever the challenge, this impoverished and repetitive school of thought always offers the same recipes. Neoliberalism simply reproduces itself by resorting to the magic theories of "spillover" or "trickle" — without using the name — as the only solution to societal problems. There is little appreciation of the fact that the alleged "spillover" does not resolve the inequality that gives rise to new forms of violence threatening the fabric of society (Paragraph 168).

Last week, in anticipation of the encyclical, the Catholic University of America sent journalists a list of faculty experts, one third of whom were drawn from the Busch School of Business.* Reading this section of the encyclical, it is clear that the text is directed at these would-be experts, not the fruit of their work. This encyclical poses questions to all of us but it poses a very specific question to the U.S. bishops who are responsible for CUA: How can they keep that business school open and under its current leadership in light of Fratelli Tutti?

These passages harken back to early sections of the encyclical that have a more anthropological focus. For example, Pope Francis writes that:

Individualism does not make us more free, more equal, more fraternal. The mere sum of individual interests is not capable of generating a better world for the whole human family. Nor can it save us from the many ills that are now increasingly globalized. Radical individualism is a virus that is extremely difficult to eliminate, for it is clever. It makes us believe that everything consists in giving free rein to our own ambitions, as if by pursuing ever greater ambitions and creating safety nets we would somehow be serving the common good (Paragraph 105).

The pope argues for a social outlook rooted in solidarity that "finds concrete expression in service, which can take a variety of forms in an effort to care for others" and is "born of the consciousness that we are responsible for the fragility of others as we strive to build a common future" (Paragraph 115). This leads to his reiteration of something St. Pope John Paul II taught in his 1991 encyclical Centesimus Annus: "God gave the earth to the whole human race for the sustenance of all its members, without excluding or favouring anyone" (Paragraph 31 in CA). Francis continues in Fratelli Tutti: "The right to private property can only be considered a secondary natural right, derived from the principle of the universal destination of created goods. This has concrete consequences that ought to be reflected in the workings of society" (Paragraph 120).

Again, I pose the question: How can the bishops of the United States justify the continuance of a business school at a university they own that so consistently and comprehensively contradicts these teachings?

Similarly, the pope highlights a virtue and a value that Pope Benedict articulated in his 2009 encyclical Caritas in Veritate: gratuitousness. There, Benedict applied it to economics and here Francis invokes it regarding treatment of migrants: "Gratuitousness makes it possible for us to welcome the stranger, even though this brings us no immediate tangible benefit. Some countries, though, presume to accept only scientists or investors" (Paragraph 139).

Will conservative Catholics who support President Trump wrestle with the implications of this teaching when assessing the president's policies towards immigrants?

Archbishop Jose Gomez of Los Angeles, vice president of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, speaks on the first day of the spring general assembly of the USCCB June 11, 2019, in Baltimore. (CNS/Bob Roller)

Equally important, how will the U.S. bishops wrestle with the fact that so many of their number, in issuing pastoral letters to the faithful in advance of the election, clearly articulate a worldview that is more consistent with that of the president than with that of the pope? Will there be sufficient votes at their November meeting, the first since the entire body completed its ad limina visits with Pope Francis, and now that they have time to read Fratelli Tutti, to reorient the conference away from the reflexive, partisan agenda that has dominated their work for more than a decade and finally to begin embracing the magisterial teachings of Pope Francis?

Consider this passage:

At a time when various forms of fundamentalist intolerance are damaging relationships between individuals, groups and peoples, let us be committed to living and teaching the value of respect for others, a love capable of welcoming differences, and the priority of the dignity of every human being over his or her ideas, opinions, practices and even sins (Paragraph 191).

Ask yourself: How many bishops in the U.S. can read these words and not experience the pangs of self-condemnation? How much "respect for others" have the bishops shown in their religious liberty campaigns or in their treatment of gay and lesbian employees?

Advertisement

Fratelli Tutti will, like all encyclicals, require several readings. There is much in this text that I have not touched on, such as the pope's discussion of religious fanaticism, but that is powerful and provocative. His pastoral style is rooted in theology but is not itself strictly theological, so our church's theologians have their work cut out for them, expounding upon the themes here and supplying the theological justifications for, and explications of, its many pastoral insights. If I could interview the pope, I would have a few thousand questions for him!

What is clear is that Pope Francis has given the church a testament of authentic solidarity at a time when our president — and his nationalistic allies abroad — offers a counterfeit of solidarity. Both varieties of solidarity are responses to the excesses and the poverties created by neo-liberalism. Yes, poverties, it is clear, as David Schindler pointed out 20 years ago, that the material wealth neoliberal economies generate is precisely coincident with the generation of spiritual and moral poverty. The whole world groans to move beyond the moral slovenliness of laissez-faire ideas. But only the pope's version represents an authentically Christian version of solidarity and, I would add, an authentically human version. This text challenges Christians in unique ways, but it challenges all. (It challenges the Catholic left also, and I will come back to that another day!)

If this pandemic does not shake us out of our post-modern cultural and moral and spiritual lethargy, what will? Pope Francis is throwing the Catholic Church and the whole world a lifeline. Will we grab it?

[Michael Sean Winters covers the nexus of religion and politics for NCR.]

*This sentence has been updated to indicate that one third, not "about half," of the experts from the Catholic University of America were from the business school.

Editor's note: Don't miss out on Michael Sean Winters' latest. Sign up and we'll let you know when he publishes new Distinctly Catholic columns.