Holy Cross Fr. Theodore Hesburgh speaks at the Illinois Rally for Civil Rights in Chicago in 1964. (OCP Media)

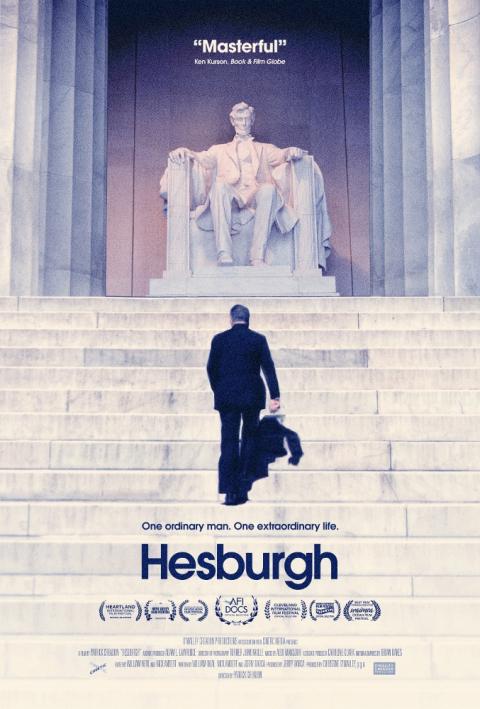

The documentary "Hesburgh" opens today in South Bend, Indiana, and in Chicago. Next week, it will open in select theaters nationwide. NCR's movie critic extraordinaire, Sr. Rose Pacatte, will be offering her thoughts, but I wanted to write a column about this extraordinary film as well. Full disclosure: Both NCR executive editor Tom Roberts and yours truly appear onscreen in the film.

Holy Cross Fr. Theodore Hesburgh (1917-2015) had an enormous influence on the church in the United States and on American culture. In the first half of the 20th century, Catholic higher education was mired in mediocrity, suffering from what Msgr. John Tracy Ellis denounced, in 1955, as the anti-intellectual "ghetto mentality" of American Catholicism. Hesburgh had been named president of the University of Notre Dame three years prior and he shared Ellis' belief that there was no reason for Catholic higher education not to aim higher. That is precisely what Notre Dame did on the ensuing decades, going from a school known mostly for its football team to a top-tier research university.

In the film, Hesburgh recalls his appointment to lead Notre Dame, saying the "vow of obedience turned my world upside down," when he was told he was to become the school's president. He had not applied for the job and, in those days, religious superiors felt no need to consult those whose lives they were about to upend. Earlier, his desire to be a Navy chaplain was frustrated when his superiors sent him to Notre Dame to get his doctorate and to teach.

The mention of his vow of obedience, twice, so early in the story demonstrates the odd fact that the vow actually liberates those who are subject to it: Hesburgh was free to take the school in new and exciting directions in part because he had been sent. The missionary need not look over his shoulder at those whose toes he stepped on to get to his station because he arrived at the command of another, and can look forward with confidence.

It is not clear — in the film or in my reading of the history of the school — whether Hesburgh's fame accounted for Notre Dame's rise or if Notre Dame's rise accounted for Hesburgh's influence, the chicken-egg conundrum. One of my few criticisms of this work is that the film does not spend enough time discussing exactly how Notre Dame went from a second-tier school to a first-rate institution.

Of course, running the university was Hesburgh's "day job" and if he had failed at that, his influence elsewhere would have diminished or vanished. I suspect that Notre Dame and Hesburgh rose together, and recall the iconic cartoon in The New Yorker in which a chicken and an egg are sitting in bed together, smoking, and the caption reads, "Should we tell them?"

That said, the film gives due tribute to Holy Cross Fr. Ned Joyce, who was Hesburgh's closest aide and the school's executive vice president. The two were best friends and Joyce's ability to run the shop allowed Hesburgh to take his show on the road. The film recounts the old joke: What is the difference between God and Father Ted? God is everywhere and Father Ted is everywhere except Notre Dame. Joyce made that possible.

(OCP Media)

Once in charge, Hesburgh was not afraid to cultivate friendships with the rich and the powerful in order to advance his school's stature. The photograph of him sitting in the backseat of a car, flanked by President Dwight Eisenhower and Cardinal Giovanni Battista Montini, the future Pope Paul VI, is priceless. Hesburgh would come to know all the popes of his time, but Montini was a friend.

Hesburgh was also not afraid to take on the ecclesial powers that be. The film recounts his tussle in the 1950s with Cardinal Alfredo Ottaviani, the powerful secretary of the Holy Office in Rome who ordered that a book Notre Dame published be withdrawn because it contained an essay by Jesuit Fr. John Courtney Murray. Murray's writings on church-state relations were suspect. Hesburgh threatened to resign if forced to withdraw the book. The cardinal, not Hesburgh, backed down.

The documentary spends a good deal of time discussing the Land O'Lakes statement in which leaders of Catholic higher education articulated the need to free our universities from clerical control. In discussing the identity of a Catholic university, Hesburgh specifically states there must be a balance. His critics make Land O' Lakes sound like an invitation to secularism, which it was not.

Yes, some Catholic universities did lose sight of their Catholic identity in the years after Land O'Lakes, but not because of the statement. And, as I stated in the film, Notre Dame was emphatically not one of those universities: Its Catholic identity is obvious to anyone who walks the campus.

Hesburgh's long involvement in the cause of civil rights is also treated extensively. First appointed to the Civil Rights Commission by Eisenhower, Hesburgh found himself prodding the bystanders in the Kennedy family, supporting the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., working hand-in-glove with Lyndon Johnson, and then getting fired by Richard Nixon. It is a fascinating story and I will let the film give you the details.

What comes through in each of these episodes is that Hesburgh was a man uniquely gifted at forging relationships and building bridges. In discussing his efforts to get the Soviets and Americans together at a meeting of the Atomic Energy Commission, we see how Hesburgh's clerical status freed him to do things an ordinary American might not be able to do. When the Civil Rights Commission deadlocked and he invited the members to abandon the hot Air Force base with lousy food in Louisiana where they were staying, and come to the Land O'Lakes retreat center for steaks and bourbon and fishing, we again see a kind of "good clericalism" at work.

Advertisement

Some of the commentary is uneven. In discussing Hesburgh's reaction to Vietnam War protests on campus, and his insistence that protests only last 15 minutes, Kenneth Woodward states: "He thought a university was a place where you discuss things, not a place where you keep people from discussing things. People who see him as a liberal hero have got to remember, no, he is more complicated than that." What was illiberal about Hesburgh's stance?

On the other hand, I thought the film's treatment of current Notre Dame president Fr. John Jenkins' decision to host President Barack Obama and the resulting controversy was very evenly done. Some of those young protesters may not have realized the school's long commitment to civil rights on account of Hesburgh's leadership, and how their sincere advocacy for the unborn was no excuse to disrespect the nation's first black president.

What emerges in the little more than an hour and a half it takes to watch this film is a laudatory portrait of a man, but not a hagiographic one. Hesburgh was a giant at a time when university presidents could be giants. Bart Giamatti at Yale would be another. Now, they are mostly fundraisers. I shudder to admit that I had to struggle to recall the name of the current president of Yale.

When Leon Panetta states, "Hesburgh became the conscience of the country on civil rights," it has the ring of truth, but of a truth that is past. Now, our polarized society may need a figure like Hesburgh to serve as its conscience, but it makes the emergence of such a figure impossible. I used to be skeptical of talk about "the Greatest Generation." These days, I am not so sure.

[Michael Sean Winters covers the nexus of religion and politics for NCR.]

Editor's note: Don't miss out on Michael Sean Winters' latest: Sign up and we'll let you know when he publishes new Distinctly Catholic columns.