A man wearing a mask for protection from the coronavirus carries groceries in Rome March 10. Italy is in a state of lockdown with extreme measures imposed on the entire country to prevent the spread of the coronavirus. (CNS/Paul Haring)

All of Italy is in lockdown. The streets of Rome are empty. The pope is saying private Masses and giving virtual, disembodied blessings via big screen in St. Peter's Square.

The cup is gone from most churches. Communion in the hand is for some a cause of great fear. Elbow bumps replace handshakes. Smiles acknowledge, at a distance, that they will have to suffice for embraces.

Cancellations are filling the calendar. Hand washing and alcohol wipes have become as much a part of daily routine as cell phones. Beware everything you touch.

March 2020 may eventually go down as the month that turned our world on its head, or slowed it to a crawl, or at least made us, more than usual, think about the precariousness of the ordinary and the power of the unseen.

The coronavirus has leaped from a Chinese seafood and poultry market late in 2019 to become a "global health emergency," according to the World Health Organization, spread at this writing to more than 70 countries, making tens of thousands ill and killing more than 3,000.

Most of us, the experts say, won't die. Most of us, they tell us, won't even get ill, or at least not seriously. But the uncertainty, the unknowing, is what most disrupts routine, wreaks havoc with everyday confidence.

Where is it? Who might have it? How, exactly, do you get it? What should we stay away from? Where might we go without too much fear?

Indeed, what do we make of all of this from a foundation of faith? Can we use the moment to see beyond the threat?

Trials, we know from our history and sacred texts, can bring clarity and deeper understanding.

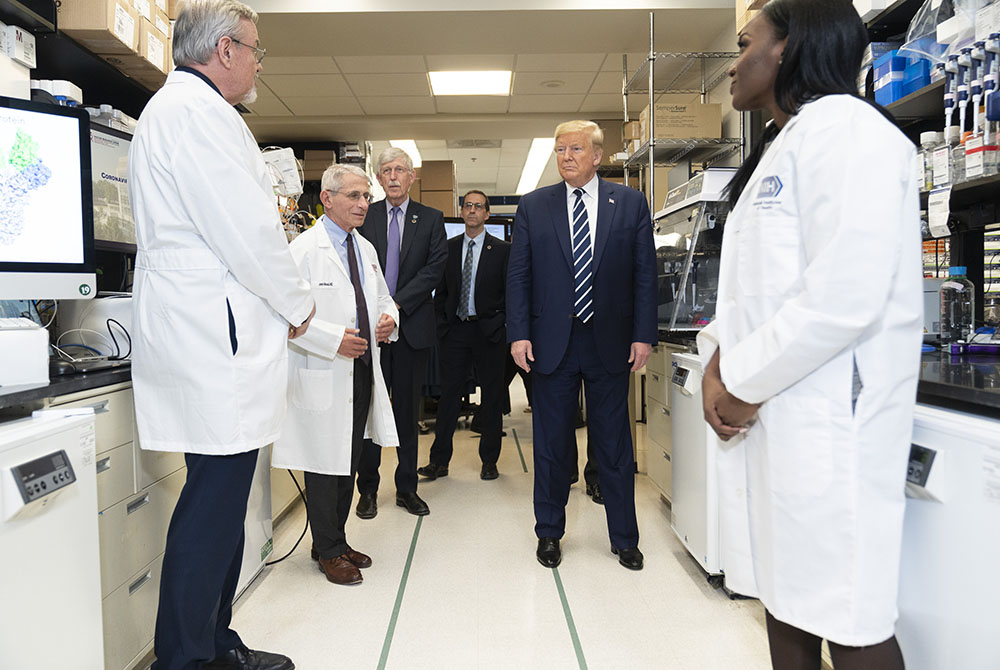

The frightening clarity revealed in the United States is that shredding the truth and denigrating scientists and other experts has consequences when crisis strikes. Whom to believe? President Donald Trump when he is declaring before experts during a visit to the Centers for Disease Control that he is some manner of medical genius who understands all about the virus because of a gene pool that includes an unidentified uncle who graduated from MIT?

Do we believe him when he contradicts the experts?

Can we believe the experts who have seen other longtime colleagues in similar circumstances fired for telling the truth or leaving their posts because they've had it with the assaults on essential bureaucracies? Are the experts ushered to the podium beside the president telling us all they can or are they hedging, fearful that they'll be the next to go if they challenge Trump's alternate universe? Might they be hedging knowing that there's no one behind them to tell even a bit of the truth?

President Donald J. Trump tours the viral pathogenesis laboratory March 3 at the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland. (Official White House Photo by Shealah Craighead)

The president boasts that we have done "great" because we closed borders. He likes to brag about that, but it's barely partially true. Our preparedness otherwise is woefully deficient. We've been way behind other countries in our testing procedures.

And when tests are finally available, big questions remain: Who gets tested? Where? How much will it cost? Does insurance cover it? Will extra help be hired to administer the tests? Can we imitate other countries that have drive-through testing?

The handoff to Vice President Mike Pence in recent days has brought a modicum of sobriety and professionalism to the response. But way behind the curve, the country is still in the planning and getting-it-together stage with nothing yet in place.

If the tragedy of this administration's assaults on truth and competence are painfully revealed, also bared is our long descent as a culture into a kind of socialized cruelty.

The roller coaster stock market reaction to the coronavirus is worrisome to a certain level of American society. At the other end of the spectrum, however, people have entered survival mode in terror of contracting the disease for a host of reasons, not least that getting to a low-wage job each day is essential to putting food on the table and keeping a roof over their heads.

As The Washington Post reported March 9, businesses are putting out lots of hand sanitizer, but when it comes to workers, there's no guarantee of sick leave.

"Although most Americans say businesses should offer sick pay, at least a dozen states, including Florida and much of the Southeast, have passed legislation since 2011 to block efforts to require medical leave," according to the report. And even in more liberal states that require sick leave, companies get around it by listing their workers as "contractors."

Advertisement

Rick Scott, former Florida governor and now a Republican senator from the state, stated the bare-knuckle rationale when he said as governor that stopping an initiative in Orlando to require sick leave was "essential to ensuring a business-friendly environment."

In a statement to the Post on March 9, Scott said about sick leave in light of the coronavirus, "businesses should have the ability to make the best decisions for their employees."

Perhaps they have that ability. The question, though, is whether business, at its paternalistic best, would choose to do what's best for their employees. Not much of a record exists to suggest that's normally the case.

It is no small irony that in a moment when we most need the assurance and support of community, we are advised to avoid others. While we wait, perhaps we can use the down time to consider with gratitude those who labor when there is no crisis, in hidden and unheralded ways, to keep us safe.

Perhaps our brush with uncertainty can also serve as entryway to solidarity with those who live regularly in uncertain and precarious circumstances. Some of us may have to contend with closed schools, altered liturgies, cancelled conferences and vacations and working from home. Consider those who, even when there is no crisis, live on the edge, in the low-wage sector, without voice and dependent on what business might think is best for them.

At a time when the common good becomes paramount and the only entity large enough to accommodate that good is government, we are left to the bumbling of an administration committed to crude diminishment of institutions and to demeaning the role of government.

The contrasts and the deficiencies which might nag around the edges in normal times become glaring in a crisis.