Grocery store check out March 28, 2020, shows pandemic precautions, masks and partitions. (CNS/Reuters/Caitlin Ochs)

They are the people who deliver your groceries, prepare restaurant and fast food, clean hospital rooms, stock warehouse shelves, and take care of your parents or grandparents in nursing homes or take care of your children in preschools.

They are, in a word, what we have come to call "essential" workers.

During the pandemic, they have literally risked their lives to do their jobs, prompting praise from celebrities, politicians and fellow citizens. But what they really want — and need — is a raise.

It is ironic that jobs that we have deemed "essential" are some of the lowest paying ones — often at or only slightly above the minimum wage. With the federal minimum wage currently stuck at $7.25 an hour ($15,080 annually for 40 hours a week), such a worker barely exceeds the federal poverty level for a single person ($12,880), never mind for a family of two, three or four.

Although 29 states (and some cities) have raised their minimum wage past the federal level, the federal minimum has not been increased since 2009. Inflation further erodes the purchasing power of low-income workers — meaning today's minimum-wage workers' earnings are worth $6,800 less annually than they were in 1968, which was the minimum wage's historical peak.

Workers' advocates and those fighting to address income inequality in the U.S. were hopeful with the election of President Joe Biden, and things looked promising when he added a $15-an-hour minimum wage provision to his first major legislative package, the $1.9 trillion COVID-19 relief bill.

But last week, Biden indicated that the wage hike is not likely to pass and began suggesting an even longer phase-in than the five years in the current proposal.

Among those opposing a hike to the minimum wage are business groups and some moderates concerned about job loss and deficit increases. A recent report by the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office found that the current Democratic proposal would cost 1.4 million jobs and increase the deficit by $54 million over 10 years.

But it would also lift 900,000 Americans out of poverty and raise incomes for 17 million people, about 1 in 10 workers, the report found. And many, if not most, of those workers are Black, Hispanic and female

Advertisement

For our country, this is a fundamental moral question. For Catholics, it's a no brainer. Our tradition clearly supports paying workers a fair, living wage for their labor: multiple references in Scripture, the preferential option for the poor in Catholic social teaching, the words of Rerum Novarum and recent comments from Pope Francis.

Last April, Francis argued for consideration of "a universal basic wage" to guarantee people have the minimum they need to live and support their families. Such a basic wage would "acknowledge and dignify the noble, essential tasks you carry out," the pope said, mentioning specifically street vendors, recyclers, small farmers, construction workers, dressmakers and caregivers.

Since the establishment of a federal minimum wage in 1938 as part of the Fair Labor Standards Act, businesses in the U.S. have pushed back on whether the government should have a role in assuring that workers have access to sustainable wages.

But the church has been clear for over a century that wages cannot be left only to market forces. From Pope Leo XIII's 1891 Rerum Novarum, Pope Pius XI's 1931 Quadragesimo Anno and Pope John XXIII's 1961 Mater et Magistra to Pope John Paul II's 1981 Laborem Exercens, the universal church has recognized the right of every worker to receive wages sufficient to provide for a family.

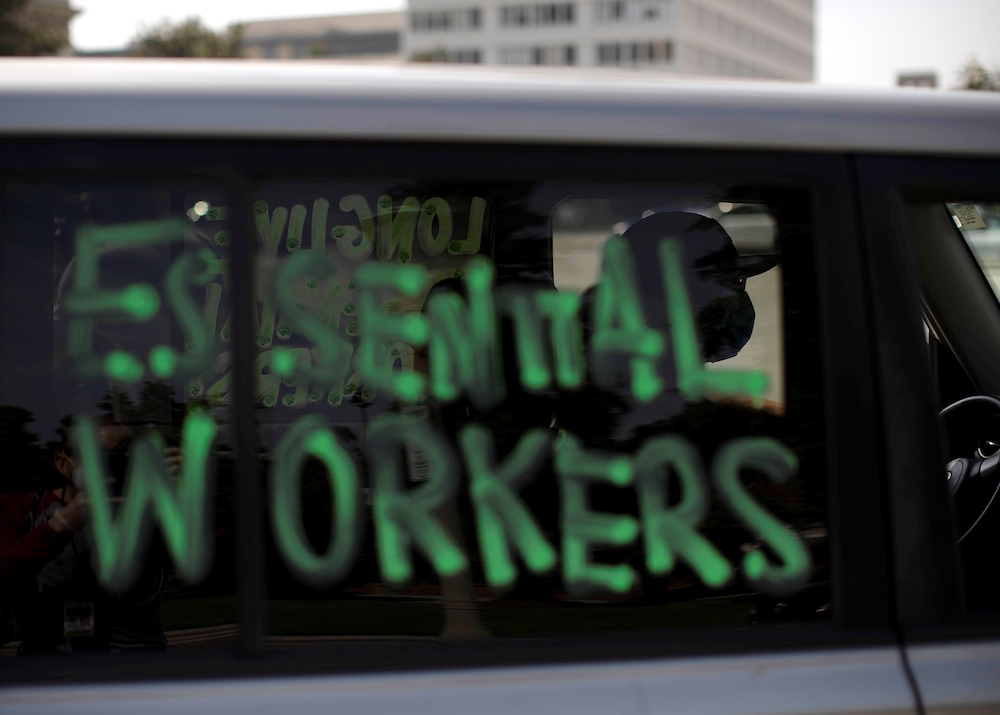

A car window in Pasadena, California, is painted with “essential workers” April 29, 2020. (CNS/Reuters/Mario Anzuoni)

The U.S. bishops, too, have consistently affirmed this principle, starting with the first major text the bishops' conference approved in 1919, their plan for social reconstruction after World War I. More recently, in their 1986 pastoral letter, "Economic Justice for All," the bishops directly connected the strength of family life to its economic stability.

Simply put: a hike in the minimum wage would mean that mothers and fathers would only have to work one job, instead of two or three, to try to put food in their children's stomachs and a roof over their heads.

Giving minimum wage earners a raise is popular among voters from both parties, and some of the strongest supporters are from people of faith. More than seven in 10 Americans, including a majority of Republicans, support raising the minimum wage, according to a 2020 survey by the Hidden Common Ground Initiative.

Even in the contentious, polarized 2020 election, 60% of Florida voters passed an amendment to raise the state's minimum wage to $15 by 2026. In 2018, more Missouri voters voted for a statewide increase to the minimum wage than cast a vote for their new senator, Josh Hawley.

There should be no such thing as the "working poor." While our faith teaches us every human person has dignity, it is especially egregious that those who work hard, especially as essential workers during a pandemic, are not afforded basic necessities.