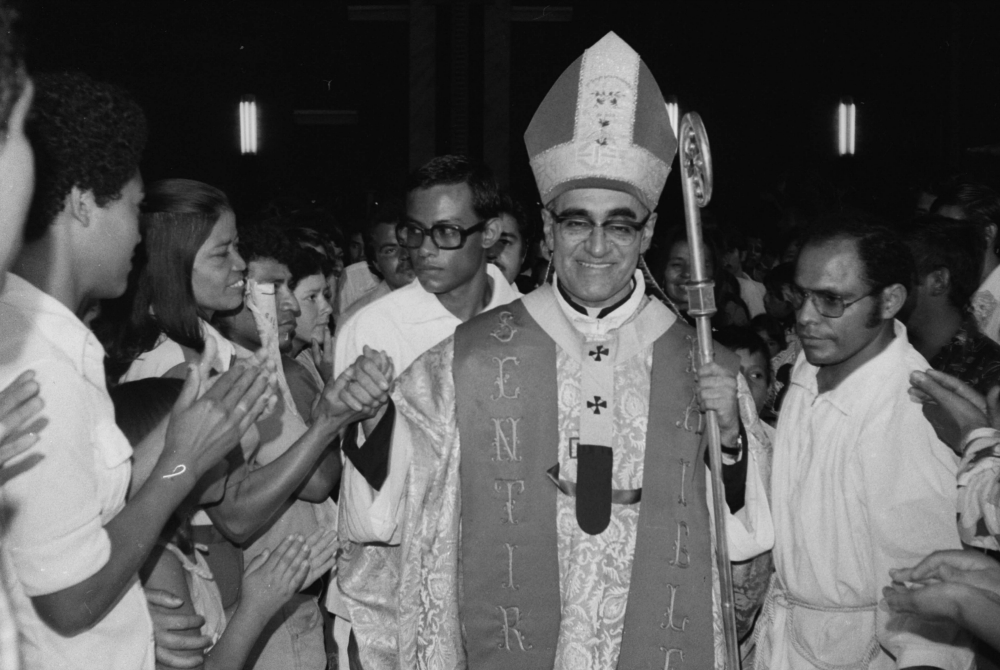

St. Archbishop Óscar Romero greets worshipers in San Salvador, El Salvador, in an undated photo. (CNS/Octavio Duran)

The problem with being canonized is that the saintly designation tends to immediately obscure the saint's humanity, that ordinary flesh-and-blood reality that answered the call to extraordinary acts of love.

It is a tendency to resist at all costs when commemorating the 40th anniversary of the assassination of St. Archbishop Óscar Romero of El Salvador. It wasn't the moment of death that established him as saintly — scores of priests and religious, we know, died at the hands of murderous death squads in El Salvador — but rather it was the life and witness that placed him, while celebrating Mass, in the crosshairs of an assassin's aim.

Chris Herlinger, international correspondent for Global Sisters Report, asks the compelling questions in his recent report from El Salvador: "Which Oscar Romero is being honored? The Saint? The humble priest? The martyred Catholic? A man entombed in history at a particular time and place, or a living example for a country still struggling with the legacy and after-effects of a decade-long civil war?"

The answer, of course, is all of the above. Romero is not divisible by theme or role or a single period of life. It was the humble — and according to those who knew him, the sometimes not-so-humble and demanding — young priest, already an accomplished preacher, who became the bishop and then archbishop.

It was the gradually awakened conscience of a cleric — operating in a deeply divided ecclesial culture within a deeply divided country — that fueled his sharp analysis and resistance to the status quo.

Advertisement

As longtime El Salvador resident and journalist Gene Palumbo wrote in 2018, Romero's transformation wasn't, as often depicted, a sudden reaction to the murder of a priest friend, Jesuit Fr. Rutilio Grande. Rather, it occurred over his time as bishop in a rural area far from the capital city, years before Grande was murdered.

Unknown to many, even those who knew him, wrote Palumbo, "Romero had changed during an extended stay, in the mid-'70s, far from the capital city. In the early '70s, as an auxiliary bishop in San Salvador, he was seen as highly conservative; that was the period when he drew the ire of the priests who were so upset by the news of his appointment as archbishop. But in 1974, he was named bishop of the rural diocese of Santiago de María. There, he drew close to farmworkers and catechists who were targeted by the military. What he saw led him to a major shift in outlook."

Romero himself described the transformation as an "evolution."

Imagine the belly-tightening fear Romero lived with for years as he addressed the murderous activity on both sides of the military and political divides as the Salvadoran civil war progressed. Imagine the terror he had to overcome daily and with each decision to confront the insidious government oppression and the activity of the notorious death squads.

The record of his sermons and the courageous radio broadcasts decrying the violence and repression is well-known. But he was, first and foremost, a pastor.

The press in his own country labeled him a communist. The powerful U.S. government to the north was supplying the military with equipment and was training troops that ultimately would be charged with gross human rights violations, often against the civilian population.

The record of his sermons and the courageous radio broadcasts decrying the violence and repression is well-known, particularly the broadcast addressed to the country's security forces the day before he was assassinated. But he was, first and foremost, a pastor.

The prophet, in this case, was also dedicated to the institution. A diary that he kept for two of his three years as archbishop is a record of the extraordinary woven as but one thread through the ordinary. His last diary entry, March 20, 1980, four days before he was killed, was an account of a day of meetings over budgetary and personnel matters, a clergy senate meeting and elections, discussions of issues involving diocesan bureaucracy with a wish for greater church unity running through it all.

Toward the end of the nearly two pages of recorded dictation, his thoughts returned again to "this situation that has me worried with regard to the financial situation and administration of our archdiocese."

Long before he was canonized, Romero was for many a saint by acclamation. He was a saint not because of some supernatural connection or by claims of miracles, nor even by martyrdom, though that was the reality.

He was a saint for raising the Gospel as a basis for opposing the activity of an overwhelmingly Catholic state. He rescued Catholicism from its role as a prop conferring respectability on power and wealth. He returned it to its proper role as an expression of faith in a God of mercy and a Christ who resides with the lowly. A proper saint, in all of his human "evolution," for our time.