(Dreamstime/Tomert)

(NCR logo/Toni-Ann Ortiz)

Forty years ago this June, the National Catholic Reporter began publishing stories about U.S. Catholic priests sexually abusing children. The articles in that first edition, on June 7, 1985, ran longer than 10,000 words.

During our 60th anniversary year, we are republishing stories from our history, including some of those stories about the sex abuse scandal exposed by NCR. They are running alongside our series, The Reckoning, examining the costs of the abuse scandal to the church.

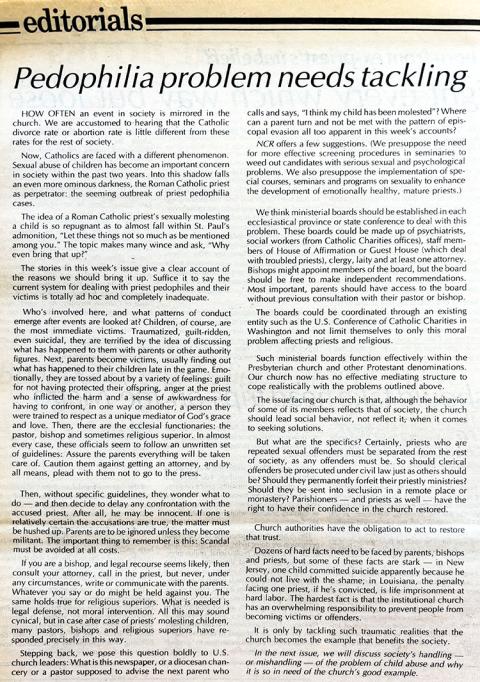

This is an editorial that ran with the original coverage on June 7, 1985.

Pedophilia problem needs tackling

How often an event in society is mirrored in the church. We are accustomed to hearing that the Catholic divorce rate or abortion rate is little different from these rates for the rest of society.

Now, Catholics are faced with a different phenomenon. Sexual abuse of children has become an important concern in society within the past two years. Into this shadow falls an even more ominous darkness, the Roman Catholic priest as perpetrator: the seeming outbreak of priest pedophilia cases.

The idea of a Roman Catholic priest's sexually molesting a child is so repugnant as to almost fall within St. Paul's admonition, "Let these things not so much as be mentioned among you." The topic makes many wince and ask, "Why even bring that up?"

The stories in this week's issue give a clear account of the reasons we should bring it up. Suffice it to say the current system for dealing with priest pedophiles and their victims is totally ad hoc and completely inadequate.

Who's involved here, and what patterns of conduct emerge after events are looked at? Children, of course, are the most immediate victims. Traumatized, guilt-ridden, even suicidal, they are terrified by the idea of discussing what has happened to them with parents or other authority figures. Next, parents become victims, usually finding out what has happened to their children late in the game. Emotionally, they are tossed about by a variety of feelings: guilt for not having protected their offspring, anger at the priest who inflicted the harm and a sense of awkwardness for having to confront, in one way or another, a person they were trained to respect as a unique mediator of God's grace and love. Then, there are the ecclesial functionaries: the pastor, bishop and sometimes religious superior. In almost every case, these officials seem to follow an unwritten set of guidelines: Assure the parents everything will be taken care of. Caution them against getting an attorney, and by all means, plead with them not to go to the press.

Advertisement

Then, without specific guidelines, they wonder what to do — and then decide to delay any confrontation with the accused priest. After all, he may be innocent. If one is relatively certain the accusations are true, the matter must be hushed up. Parents are to be ignored unless they become militant. The important thing to remember is this: Scandal must be avoided at all costs.

If you are a bishop, and legal recourse seems likely, then consult your attorney, call in the priest, but never, under any circumstances, write or communicate with the parents. Whatever you say or do might be held against you. The same holds true for religious superiors. What is needed is legal defense, not moral intervention. All this may sound cynical, but in case after case of priests' molesting children, many pastors, bishops and religious superiors have responded precisely in this way.

Stepping back, we pose this question boldly to U.S. church leaders: What is this newspaper, or a diocesan chancery or a pastor supposed to advise the next parent who calls and says, "I think my child has been molested"? Where can a parent turn and not be met with the pattern of episcopal evasion all too apparent in this week's accounts?

NCR offers a few suggestions. (We presuppose the need for more effective screening procedures in seminaries to weed out candidates with serious sexual and psychological problems. We also presuppose the implementation of special courses, seminars and programs on sexuality to enhance the development of emotionally healthy, mature priests.)

The National Catholic Reporter page with the editorial that ran on June 7, 1985, with the newspaper's original coverage of clerical sexual abuse of children (NCR photo/Toni-Ann Ortiz)

We think ministerial boards should be established in each ecclesiastical province or state conference to deal with this problem. These boards could be made up of psychiatrists, social workers (from Catholic Charities offices), staff members of House of Affirmation or Guest House (which deal with troubled priests), clergy, laity and at least one attorney. Bishops might appoint members of the board, but the board should be free to make independent recommendations. Most important, parents should have access to the board without previous consultation with their pastor or bishop.

The boards could be coordinated through an existing entity such as the U.S. Conference of Catholic Charities in Washington and not limit themselves to only this moral problem affecting priests and religious.

Such ministerial boards function effectively within the Presbyterian church and other Protestant denominations. Our church now has no effective mediating structure to cope realistically with the problems outlined above.

The issue facing our church is that, although the behavior of some of its members reflects that of society, the church should lead social behavior, not reflect it, when it comes to seeking solutions.

But what are the specifics? Certainly, priests who are repeated sexual offenders must be separated from the rest of society, as any offenders must be. So should clerical offenders be prosecuted under civil law just as others should be? Should they permanently forfeit their priestly ministries? Should they be sent into seclusion in a remote place or monastery? Parishioners — and priests as well — have the right to have their confidence in the church restored.

Church authorities have the obligation to act to restore that trust.

Dozens of hard facts need to be faced by parents, bishops and priests, but some of these facts are stark – in New Jersey, one child committed suicide apparently because he could not live with the shame; in Louisiana, the penalty facing one priest, if he's convicted, is life imprisonment at hard labor. The hardest fact is that the institutional church has an overwhelming responsibility to prevent people from becoming victims or offenders.

It is only by tackling such traumatic realities that the church becomes the example that benefits the society.