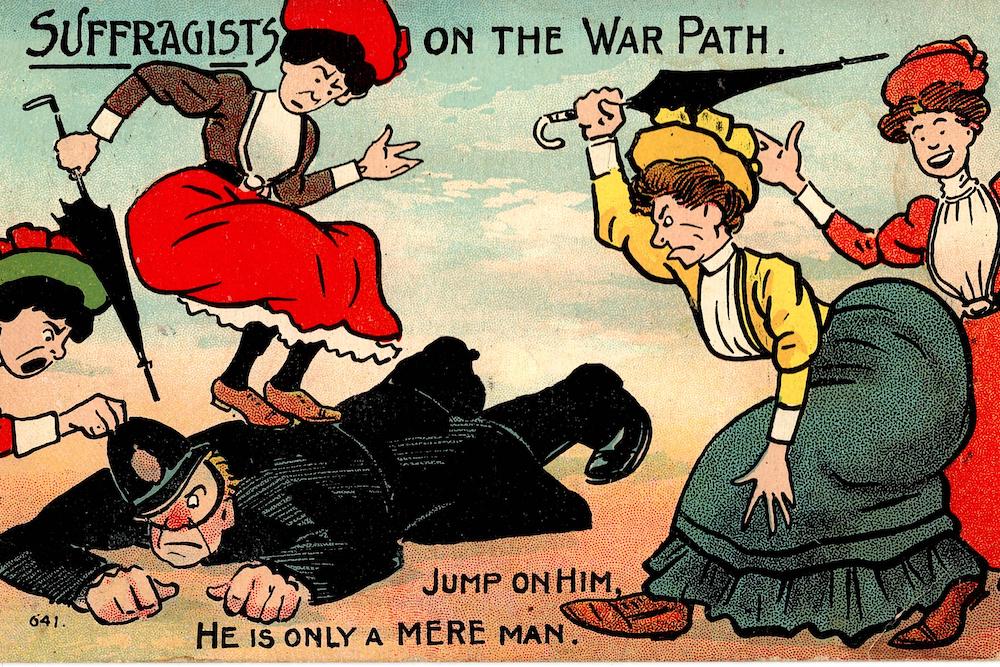

Anti-suffrage postcard (Flickr/Women's Library at the London School of Economics and Political Science)

Tomorrow marks the 100th anniversary of the day that women's right to vote was enshrined in the Constitution of the United States. The passage of the 19th amendment was the result of more than 80 years of women agitating, picketing and lobbying; some endured jail time and force-feedings when they went on strike to protest their arrests.

The moment celebrated as the official "start" of the suffrage movement was the first ever women's rights convention held 1848 in Seneca Falls, New York. A week before the event, the organizers put out an ad in the local paper, advertising it as a convention "to discuss the social, civil and religious condition and rights of Woman." Even in those earliest days of the fight for suffrage, women realized, and spoke openly about, the need for equality not only in the government, but also in the church.

As we celebrate the suffrage centennial, it's important for women, particularly Catholic women, to remember the arguments that anti-suffragists made in their opposition of a woman's right to vote. They sound eerily similar to the Catholic hierarchy's current arguments against women's decision-making power in the church and against women's ordination.

The reason that women do not enjoy any form of leadership in the church is essentially because of its teaching that God designed men and women for separate and distinct roles in society and the church.

This idea that women and men are essentially different buttressed many arguments against suffrage and could even be found on the lips of female anti-suffragists, of which there were many. Frances Cleveland, wife of the 22nd and 24th President Grover Cleveland, famously wrote that "men's and women's roles had been assigned long ago by a higher intelligence."

Advertisement

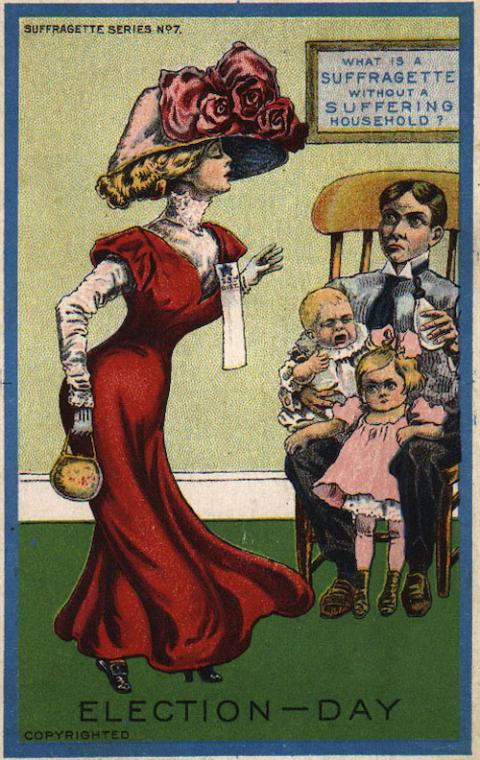

Male anti-suffragists meanwhile fretted that a woman's right to vote would destroy the family by disturbing and interrupting household order. Posters popped up showing husbands helplessly trying to take care of infants and while their wives boss them around. In one remarkable image, called the "Suffragette Madonna," a man is visualized as Mary holding the child Jesus.

Those who, today, oppose women having leadership power in the church also draw upon the rhetoric of family values and strict gender roles. More than one pope has claimed that the church would rupture if women were allowed to perform the duties that God wants performed solely by men.

Anti-suffrage postcard by the Dunston-Weiler Lithograph Company of New York, part of a 12-card series, 1909 (Palczewski, Catherine H. Postcard Archive. University of Northern Iowa. Cedar Falls, Iowa)

Some anti-suffragists demonized women who wanted the vote, claiming that they wanted to be men. This is reminiscent of an idea that Pope Francis has often repeated that that feminists are "chauvinism in skirts," and that feminism "puts women on the level of a vindictive battle."

As I wrote back in 2013, Francis' language suggests that "equal treatment under the law and equal standing in society should be understood as women trying — like vindictive macho men in female drag — to assert their superiority over men."

Jorge Bergoglio was born in 1936 — well after women got the vote in the U.S. — but, even his modern rhetoric would fit right in with the turn-of-the-century anti-suffrage brigade.

Other opponents to women's suffrage used an argument that I actually hear from some Catholics. Anti-suffragists argued that women shouldn't get the vote because they would be sullied by the rough and dirty world of politics. They believed that somehow they were protecting women by blocking them from enfranchisement.

This reminds me of the well-intentioned, progressive Catholics who argue that the priesthood is so corrupt and clericalism so sordid that women should not be exposed to it. They should wait, these Catholics suggest, until the priesthood is reformed. Women are too pure and too good to be subjected to the priesthood, let alone want it.

If women have to hold out for equality until the all-male patriarchy wakes up, relinquishes power and decides to transform itself, they'll wait forever. That's not justice, and it's not what our suffrage foremothers would have wanted for us.

Anti-suffrage women could be formidable opponents in the struggle to enfranchise women. Many claimed that women didn't need or even want the vote. According to the new PBS Series "The Vote," Mrs. Gilbert Jones, the daughter-in-law of the founder of The New York Times, said that that there had been much progress for women over the past 50 years, but pointed out that it had been achieved without the ballot. And Annie Nathan Meyer, founder of Barnard College, saw no reason for females to achieve the vote and said she doubted it would make a difference.

Anti-suffrage women believed in exerting indirect influence. But they, of course, were white and wealthy and had access to legislators and judges. But their argument is not unlike those who believe that having married male priests is a "step in the right direction" for women because it would allow wives and daughters to have some circuitous sway over the men in power. It also reminds me of the women who say they don't want to be priests because they already have such a unique, special role in the ministry of the church.

Kate McElwee and Deborah Rose-Milavec projected images of their "Votes for Catholic Women" sign around Vatican City at night during the 2019 Amazon Synod. (Provided photo)

What many still do not realize is that making women truly equal in the church is about more than ordaining women. It's about acknowledging that people of all genders are equal in the eyes of God, an acknowledgment that is essential for women to achieve enfranchisement and access to freedom and authority in their church. And if a church as large, powerful and influential as the Catholic Church says women deserve equal power, it would have an untold impact in countries, cultures and societies that treat women and other gender minorities as inferior.

Black and queer women suffragists understood well how crucial direct power and equality are. Any celebration of women heroes of the 19th Amendment must acknowledge the racism of many of its key leaders, like Susan B. Anthony and Alice Paul, who were willing to silence and erase Black women in order to move forward their suffragist agenda.

Deborah Rose-Milavec and Kate McElwee pose in front of the closed doors of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith with their "Votes for Catholic Women" projection. (Provided photo)

The word "suffrage" comes from the Latin word for judgment or vote. In antiquated English, it also means a series of intercessory prayers. Today, Catholic women are embracing this dual meeting and aiming the suffragists' "Votes for Women" campaign directly at the Vatican.

During the past two synods of bishops in Rome (the one on youth in October 2018 and the one on the Amazon in October 2019), there have been headline-grabbing demonstrations in front of the Vatican's Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, the office that enforces orthodoxy with official church teaching.

The first protest erupted in October 2018 with a group of 20 women and men from six continents chanting "Let Women Vote." It ended with the Roman police storming the scene, detaining protestors and confiscating their passports, as I wrote in NCR at the time. The incident led The New York Times to dub the movement and its leaders, Kate McElwee and Deborah Rose-Milavec, "modern-day suffragists."

The following year, during the 2019 synod, the two campaigners set out at night into the streets of Vatican City with a small projector, casting images of their "Votes for Women" logo on the imposing doors of the CDF, the obelisk in St. Peter's Square and the Aurelian walls.

While not everyone in the movement believes in women's ordination — advocating for the issue, by the way, is still an excommunicable offense — they could all agree that it was far past time for women to at least have a vote in the synod.

Some Benedictine nuns from Fahr Monastery near Basel, Switzerland, led by their Prioress Irene Gassmann, traveled to Rome by bus to protest the 2019 Synod. The nuns wore orange capes that said "Votes for Catholic Women." (Deborah-Rose Milavec)

The "Votes for Women" campaign got so much traction, that Benedictine community of habited nuns from Basel, Switzerland, hopped on a bus to Rome to demonstrate in front of the Vatican during the synod in October 2019. Their argument? A religious brother had been granted voting rights at that synod, but none of the 20 nuns invited to the synod were given this privilege, even though men and women religious share the same canonical status. Universal suffrage is a unifying force among Catholic women to this day.

Harriot Stanton Blatch, an abolition journalist and the daughter of suffrage pioneer Elizabeth Cady Stanton, was recalled as saying, "you must keep suffrage every minute before the public so that they are used to the idea and talk about it, whether they agree or disagree." Whether the issue is votes for women in church or state, I think we can all agree that she was quite right — and Catholic women are doing just that.

[Jamie L. Manson is a longtime, award-winning columnist at the National Catholic Reporter. Follow her on Twitter: @jamielmanson.]