An American sailor, an American Red Cross nurse and two British soldiers celebrate the signing of the Armistice, near the Paris Gate at Vincennes, France, Nov. 11, 1918. (Wikimedia Commons/Imperial War Museum)

At 11 a.m. on Nov. 11, Europeans in many nations will pause, stop work, listen to ringing church bells, bugle calls and dirges while public officials, clergy and descendents of the honored dead recall anew the human price of the nearly four years of war (1914-18) that ended 100 years ago.

Fighting engaged a score of European armies, plus militia from Africa, the Ottoman Empire of the Middle East, India, Australia, New Zealand, Canada and the United States, which sent 2 million troops "over there" in 1917 and 1918.

Hard to comprehend that some 65 million men — and 8 million horses — were mobilized into land, sea and air forces between July 1914 and Nov. 11, 1918, the day the slaughter stopped with a cease-fire that had been drafted aboard a train hidden in the French forest of Compiègne. At war's end, 8.5 million in the armed forces had been killed and 21 million wounded. Some 7.7 million more were reported missing, and presumed dead, or held as prisoners. And 10 million civilians perished due to famine, privations, sicknesses and bombardments. Millions more would join them as the Spanish flu crossed borders and claimed some 8 million lives in Europe alone during the conflict.

Adieu, a generation and its progeny.

In spite of these grim realities, the Allies — France, Britain and her colonies, Belgium, Italy, Serbia and a host of European countries — celebrated the defeat of Germany and the end of trench warfare. Living underground for months on end meant enduring cold, lack of sanitation and sleep, K-rations, rats, lice, mud and often water thigh-high. To emerge and go "over the top" as British Tommies termed it, risked exposure to gunfire, poison gas, the point of a bayonet, or at times strafing from enemy planes. But it could also mean sunlight, fresh air and the scent of the seasons, as soldiers recorded in their war diaries.

An American machine gun company passes through the ruins of a French village in advance of the Battle of Saint-Mihiel in September 1918. (U.S. National Archives)

Nothing is more uplifting than seeing Flanders' fields on a beautiful spring day when floral trees disguise the granite corridors of buried corpses. Men who died within a few meters of one another in a war of attrition that allowed hardly any progress by the advancing army now lie ever so close for another aeon. Nearly 31,000 Americans rest among them in Flanders and in other European graveyards.

My Belgian father-in-law, born two months premature in 1915 and delivered by a German Army medic who had been billeted in West Flanders, told me that when Flemish farmers first put their plows into the fields in 1919, the earth ran red with blood. Apocryphal? "Not bloody likely," British troops could attest when so many of them and Frenchmen and Germans and Belgians and Americans died side by side.

Returning to Europe recently — my home some 13 years in the 1960s, '70s and '80s — I couldn't help but notice reminders of the upcoming centenary of the armistice. In two of my previous homes, Belgium and Britain, where the "Great War" still haunts citizens, Armistice Day preparations were well underway.

A brief visit to Ripon Cathedral in North Yorkshire, England, brought me face to face with the place English poet Wilfred Owen came when he visited the great medieval church on his 25th birthday. On the day the war ended, Owen's parents received a telegram informing them of his death on Nov. 4, 1918.

My uncle, Jack Murray, lived to tell about the war. Not that he spoke much of his two years in France, Belgium and Germany, where he served in the army of occupation after the armistice was signed. Once when I was back briefly from Europe, visiting family in Minneapolis, Jack was quick to quiz my Belgian husband about places where he had fought with the 151st Field Artillery, 42nd Rainbow Division under the command of Gen. Douglas MacArthur. My husband had heard of MacArthur and of most of the Belgian sites, though he had visited few of them.

Jack, by then in his mid-70s, spoke admiringly of European horses that had pulled the artillery's gear and weapons. He never returned to Europe after his demobilization in 1919, but when Jack recalled his war days, his eyes shone like a young man eager to embark on his first adventures abroad. Among them was perching himself in a tree observing enemy movements through a pair of field glasses. Luckily for Jack, his commanding officer ordered him out of the tree when he perceived the enemy advancing. Seconds later, the tree was blown to bits by a German shell, but Jack had both feet safely on the ground.

Advertisement

My uncle, who died just short of his 96th birthday in 1992, had served in the U.S. Army on some of the war's major battlefields, including Saint-Mihiel, Argonne Forest and Verdun. I recalled these tales of valor when my 6-year-old grandson asked me recently whether I knew anyone who flew with the Red Baron. I pretended that Jack Murray was in a dogfight with Manfred von Richthofen, Germany's top fighter pilot, whose red Fokker Dr.I triplane went after Ace Murray's Sopwith Triplane. Grandson George and Bonma buzzed around the living room, skirting over tables, across couches and high above corner lamps — only two and four generations removed from our "Great War" heroes.

I hope Americans — especially schoolchildren — will hear about more than the Red Baron on this momentous centenary of war's end. Perhaps a teacher will have them read Owen's "Anthem for Doomed Youth" and let them weigh in on what makes a world war. A social studies or geography class might be just the venue to look at a map of Europe in 1914 and another one after the war ended.

What happened to the Ottoman and the Austro-Hungarian empires? Where did Yugoslavia come from and why was Russia now called the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics? Which lands formed the republics? How had Africa and Asia changed and the British Commonwealth and the French colonial territory expanded after the major powers signed the Treaty of Versailles in June 1919?

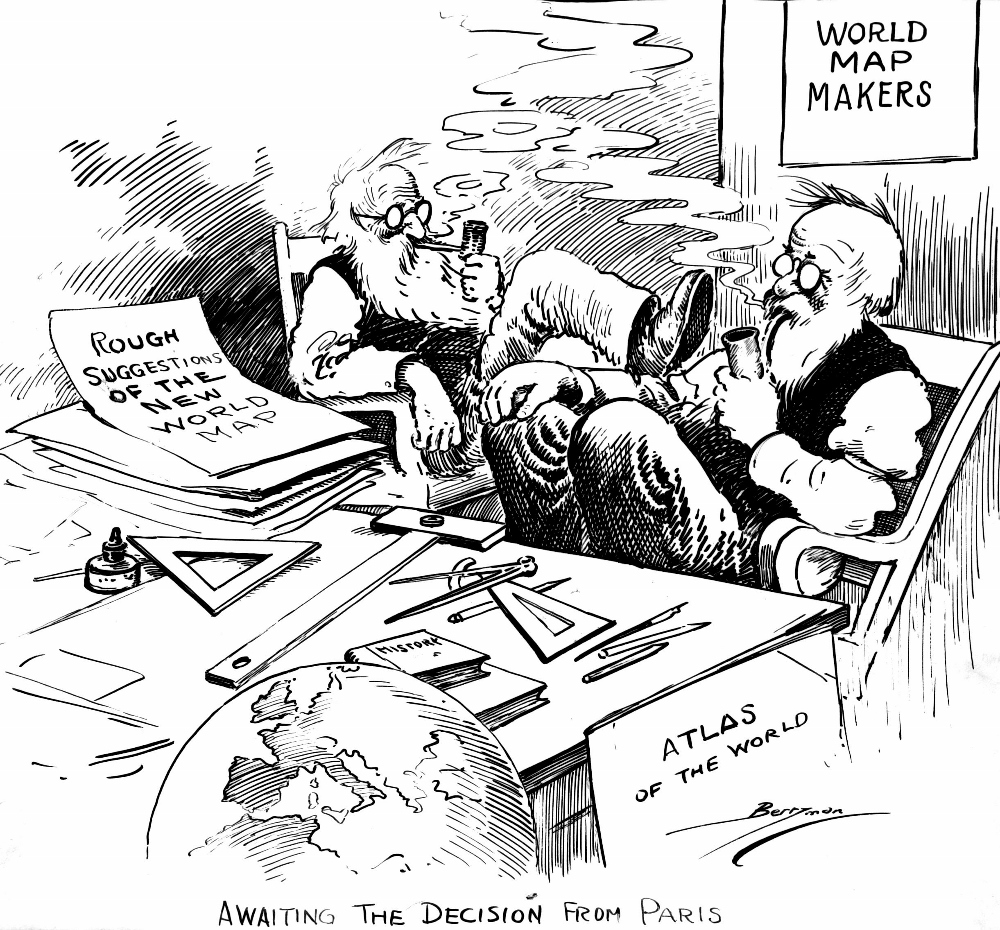

A January 1919 cartoon by U.S. cartoonist Clifford Berryman comments on the Great War's peace negotiations then ongoing in Paris. (U.S. National Archives/Berryman Political Cartoon Collection)

Or how about a Biography Day with individual students presenting some of the major figures of the 20th century and how they were related to World War I: Adolf Hitler, Joseph Stalin, Grigori Rasputin, Czar Nicholas II, Vladimir Lenin, Leon Trotsky, Winston Churchill, David Lloyd George, T.E. Lawrence, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, Georges Clemenceau, Kaiser Wilhelm II, Gen. John Pershing and Woodrow Wilson. For girls who may not like presenting military figures, why not tell the tales of nurse Edith Cavell, suffragette Emmeline Pankhurst or spy Mata Hari?

While women did not go to war as combatants, thousands went to factories where they made uniforms, armaments and food products for the troops. Many learned to drive and hundreds became ambulance drivers and medical aides on or near the front. In Britain, women won the right to vote, but they, their children and the elderly did not avoid suffering; 109,000 died due to food shortages and 183,577 by the Spanish flu.

Middle and high school students are not too young to examine the rise of technology during warfare. German engineering excelled in machine gun and anti-aircraft manufacturing, while Britain was quick to create an all-metal fighter aircraft and a heavy bomber. Both the Allies and the Central Powers used mines, gas, shrapnel, torpedoes, machine guns, heavy artillery and grenades to finish off one another.

Shrapnel from World War I is displayed at In Flanders Fields Museum in Ypres, Belgium. (Wikimedia Commons/Sandra Fauconnier)

Often enough, we've heard, but paid insufficient attention to, the adage that the seeds of the next war are sown in the just-concluded conflict. Never was this truer than with the Treaty of Versailles, drafted in Paris over six months by the heads of Britain, France and America and their deputies.

When the Germans were summoned to sign it, they were shocked by its terms, especially the French occupation of the coal-rich Saarland; the loss, too, of territory that had been taken from France in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71; and the almost total demilitarization of Germany's land, air and sea forces. Down to an allowed 100,000-man military and with assigned reparation debts of $34 billion owed largely to Britain and France, Germany felt humiliated and the victim of resentment, particularly on the part of the French, whose land Germany had invaded, poisoned and trampled for nearly four years.

In just two decades, the world would see Germany rise from the ashes of defeat to take vengeance on most of Europe. As the poet Owen penned before dying at 25: "The pity of War. The Poetry is in the pity. ... All a poet can do today is warn."

[Patricia Lefevere is a longtime NCR contributor.]