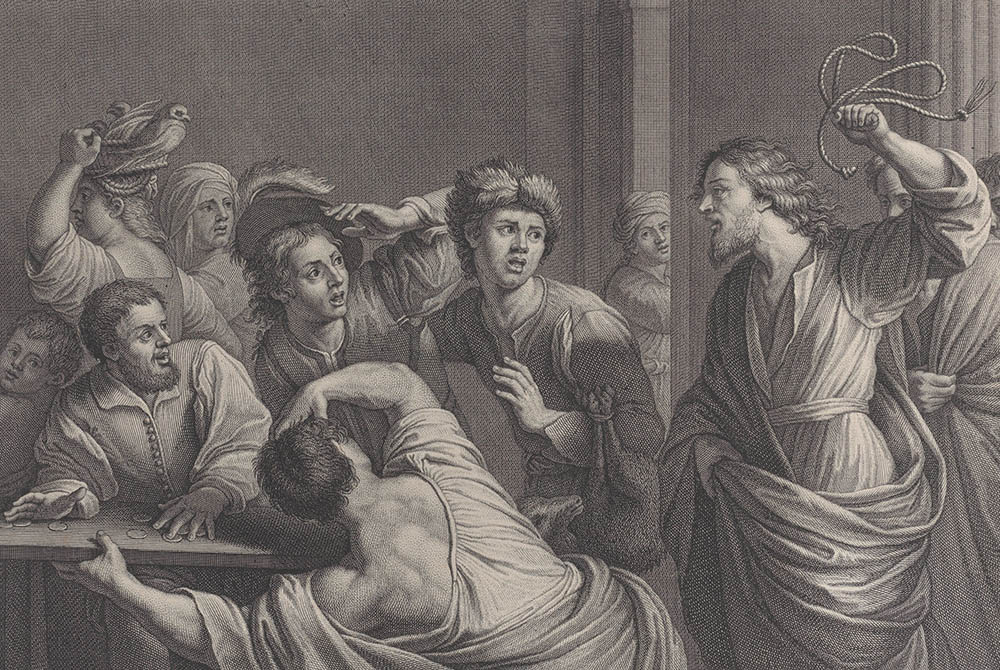

"Christ driving the merchants from the temple," by Jean-Baptiste Haussard, after Bartolomeo Manfredi, a circa 1729 print (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, D-New York (Flickr/NRKbeta/Ståle Grut)

As Jesus cleansed the Temple dramatically and violently, it's vital to confront "money changers" hawking their wares in the "temple" of U.S. democracy today. That's what newly reelected U.S. Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez told National Catholic Reporter in late October, invoking her favorite biblical story to illustrate incremental annexation of sacred space.

In citing this tale, which appears in each Gospel, the junior lawmaker known as AOC lends contemporary explication, perhaps inadvertently, to a narrative with a sinister past. To early Christians, it cast "other" Jews as rejected by God, and medieval adherents leveraged it to associate Jews with money and power. Prevailing conspiracy theories of unduly influential Jews continue to mine the story, say scholars with expertise in early church history and Jewish-Christian relations.

Scholars are divided on the degree to which Ocasio-Cortez welcomes anti-Jewish constituents in her support of the Palestinian cause but agree she and fellow Christians ought to grasp more fully the history of anti-Jewish reading of the Temple-cleansing narrative.

Christians should forgo phrases like "30 pieces of silver" and "the money changers from the Temple" even if they aren't invoking Jews consciously, according to Jonathan Karp, director of Judaic studies at Binghamton University, SUNY, who acknowledged that the anti-Jewish connotations arose centuries after the Bible was recorded.

"I like AOC, so I'm not singling her out," he said. "When Jews like me hear them we flinch, because we know that they have been put to insidious use."

Neither Ocasio-Cortez's congressional nor campaign office responded to multiple requests for comment.

The more accurate way to read the story is that Jesus criticizes some money changers but praises others, according to Curtis Hutt, associate professor of religious studies at University of Nebraska Omaha.

"I don't think AOC, who is obviously not a full-time historian of this period, knows anything about the positive treatment of discerning, honest, and faithful money changers in early Christian traditions," he said. "She probably can't envision Jesus or the Church Fathers telling people to be good money changers — even though this is perfectly sensible."

Like the overwhelming majority of Christians today, Ocasio-Cortez has been likely influenced by medieval Christian, anti-Semitic narratives of "evil Jewish money changers — some of whom are implicated in the death of Jesus," Hutt thinks. He added that many still associate Jews and money, and contemporary conspiracy theories implicate Jewish money changers.

"Given the anti-Semitic way that many view the story, when AOC raises it she should be sensitive to how it might be taken by others," said Hutt, who believes President Donald Trump too subscribes to medieval anti-Semitic notions of Jews and money.

"I think we have been heading backwards as a society when it comes to anti-Semitism in the last few years," he said. "Given the great progress made in Roman Catholic and Jewish relations since the 1960s, I would hate to see any slip back on this remarkably positive front."

Malka Simkovich, Jewish studies chair and director of Catholic-Jewish studies at Chicago's Catholic Theological Union, thinks Ocasio-Cortez allows herself to be heard in certain ways without spelling metaphors out. AOC isn't using dog whistles but gives herself plausible deniability to claim she didn't mean what she said, Simkovich believes.

"It's enough for her to say, 'I like this story' and to allow those who read it in an anti-Jewish way to interpret it," she said. "I don't think it's anti-Semitic, but she's allowing a broad tent of people to ally with her who associate Jews with power and money."

In recent weeks, New York Jewish leaders have complained of Ocasio-Cortez's apparent disinterest in meeting. "There is a lot of frustration," Michael Miller, executive vice president and CEO of the Jewish Community Relations Council of New York, told Jewish Insider early last month. Days prior, AOC withdrew from an Americans for Peace Now event celebrating former Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin, who was assassinated in 1995.

And in June 2019, domestic and Israeli Jewish organizations criticized Ocasio-Cortez for calling migrant detention centers "concentration camps." That phrase has a long history, including the Holocaust camps and other ethnic groups who have been rounded up by totalitarian governments, but prominent Jewish leaders and organizations said at the time that the term was inappropriately used.

Where many colleagues approach Ocasio-Cortez with a hermeneutics of grace, Simkovich adopts a hermeneutics of suspicion at a time when the Holocaust is seen as ancient history and Jews are perceived as "white" and powerful.

"In this world where identity politics reigns supreme, Jews aren't being allowed into spaces that advocate for the powerless and vulnerable," Simkovich said. "AOC is allowing herself to be interpreted as signaling that with the story that articulates and underscores differences between Christian universalism and Jewish particularism."

"AOC is smart, and I think she sees little advantage but a lot to lose in reaching out to Jewish organizational leadership now," she said. "That's how I read her perspective."

Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (Wikimedia Commons/Senate Democrats)

Whatever tension may exist between AOC and many Jewish leaders and rank and file, her preferred biblical tale is complicated even in the Gospels. Mark 11, as retold with slight variation in Matthew 21 and Luke 19, details Jesus overturning money-changing tables and dove-seller seats, quoting Isaiah 56:7 — "My house will be called a prayer house for all." He accuses them of reducing the Temple to "a den of thieves."

In John 2, meanwhile, Jesus whips those changing money and selling oxen, sheep and doves and tells the latter to cease making the Temple "a house of merchandise." They ask for a sign, and Jesus tells them to raze the Temple, which he will raise again in three days. This confuses the masses, who figure architecture that took 46 years to build can't be reconstructed in a hundredth of one percent of that span. But, John informs, Jesus spoke of the temple of his body.

A close reading reveals that what some informally call the "Temple tantrum" wasn't necessarily a protest of money changing broadly or even in the Temple, according to Simkovich.

"He was symbolically envisioning the coming destruction of the Temple and the notion that the religious function of this Temple was coming to an end, to be replaced by a new form of divine worship and penance," she said. Jesus rebukes those who reject him as the replacement for what he considered the irrelevant, corrupted Temple, she added.*

Money changing wasn't stigmatized in the first century, as pilgrims had to exchange their cash for Judean currency to purchase animals for sacrifice and pay Temple taxes. Money changers "were instrumental to performing a sacred act of devotion," said Binghamton's Karp. "It's insane to talk of Judas or the money changers in the Gospels as 'Jews' when almost everyone depicted in the Gospels, including of course Jesus himself, was a Jew."

Later interpretations "distorted" original Gospel meaning, and an initial anti-Jewish motif of "Jews and materiality, carnality, literalism" gave way to one of Jews and money. In other words, Karp said, Jews were "missing the inner spiritual message of biblical prophecy because of an exclusive focus on the external [and] ritualistic."

Advertisement

By the Middle Ages, Jews were more concentrated in commerce, including occasionally money lending. They weren't forced to change money, but being barred from other areas, some gravitated to it. Christians began to apply New Testament texts about Jewish money changers and Judas' betrayal of Jesus for 30 silver pieces to Jews collectively, and medieval religious plays and art represented Judas as a Jewish moneylender and money changers in the Temple courtyard as particularly Jewish, Karp said.

In medieval Europe, Christian inability to loan money with interest to one another created opportunities for Jewish moneylenders, but the church taxed heavily the interest they accrued. Jews had to keep raising rates to remain in business.

"This fed into the long-standing reputation of Jews as greedy moneylenders, who gouged vulnerable Christians and who were societal pariahs, who drained good people of their resources," Simkovich said. Jewish moneylenders "surely sowed resentment among Christians who viewed Jews as holding power over them," she said. "They viewed this dependency on Jews as an unjust reversal of the Jews' supposed destiny."

But long before Jews lent money to Christians — as far back as the Hellenistic era — Jews were seen as hostile to host governments and insufficient contributors to society, Simkovich said. Jews largely changed Jewish money in the first century, so no one complained about a necessary profession. But in the Middle Ages, Christians tended to connect their belief that God rejected Jews and doomed them to suffer with their money-changing profession.

"Unfortunately, many Christian readers, and even many biblical scholars, presume that the money changers* in this story are corrupt and exploitative and that their work reflects the corrupt and exploitive behavior of Jews, especially Jewish administrators of the Temple," Simkovich said. "I can't tell you how often I see this presumed in biblical scholarship."

Another interpretation of the Temple-cleansing story that troubles Simkovich holds that Jesus — qua community-activist outsider advocating for the most vulnerable — inspires grassroots change from outside systems that are too broken to fix internally. After all, he violently overturned money changing tables instead of dialoguing with the other side. This view, to Simkovich, sets up a false binary between Christianity and Judaism when it comes to protecting the powerless.

"That's not historically accurate," Simkovich said. "Jesus is not fighting Judaism. He's working within it and foregrounding what he views as being Jewish values. That's not to imply that all Pharisees or all Temple administrators are corrupt."

[Menachem Wecker is a freelance writer based in Washington, D.C., and a National Press Club board member.]

*These sentences have been clarified from earlier versions.