Pope Francis and church leaders from around the world attend a Mass on the last day of the four-day meeting on the protection of minors in the church Feb. 24, 2019, at the Vatican. (CNS/Maria Grazia Picciarella)

A widely known and well-respected world figure is once again taking on the Catholic Church over its abuse crisis, speaking more forcefully than ever before.

Asking for forgiveness "is not enough," he says.

Victims, he says, have to be "at the center" of everything.

He insists there must be "concrete actions to repair the horrors they have suffered and to prevent them from happening again."

The Catholic Church must set an example in helping to solve the problem and "bring it to light," he says.

Strong words, no?

Here's the problem, though: the man saying these things is the man who can do these things.

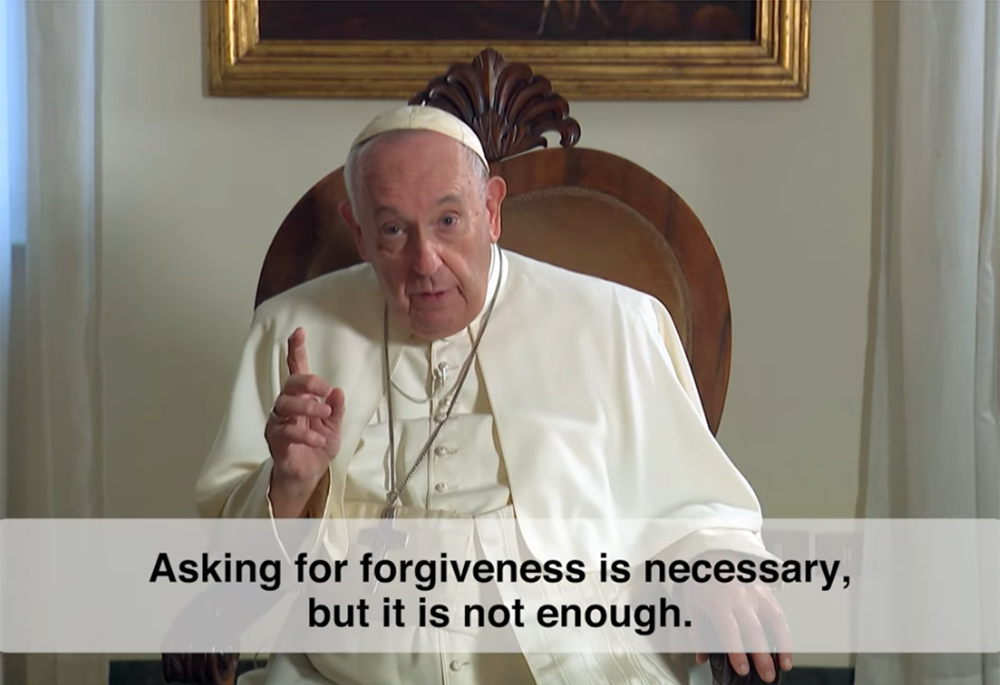

Pope Francis himself, in a carefully choreographed new video released earlier this month (March 2), talks tough about abuse, as though he is someone outside the church looking in.

But he is, of course, the ultimate church "insider," the man at the top of a very clear and rigid hierarchy, the one person who has the most power — indeed, nearly limitless power — to prevent abuse, expose wrongdoers, release records, rebuild trust and help victims heal.

But he refuses to do so. Instead he repeatedly just pontificates (excuse the pun) about the crisis, often in eloquent, even heart-wrenching ways, without following through with concrete, effective reforms.

Pope Francis speaks about abuse and survivors of abuse in a video released March 2. (YouTube/The Pope Video)

To many survivors like me, this is absolutely maddening. As we approach the 40-year mark in the U.S. church scandal, it seems like the gap between what top Catholic officials say about abuse and what they do about abuse has never been bigger.

Admittedly, Francis has met with more victims and apologized more abjectly than Benedict or John Paul II. He has tweaked or toyed with more internal church policies and protocols on abuse (which his supporters then try to portray as far more substantive than they really are).

He has broadened the definition of abuse to include vulnerable adults. And he has expanded the long-standing practice of bishops investigating and judging accused priests to bishops investigating and judging accused bishops as well.

And he has empowered bishops to not only investigate and judge accused abusive priests but to do likewise with accused enabling bishops.

But consider what Francis could do and hasn't. And imagine the shock waves that would reverberate through the entire church hierarchy — and the cover-ups that would be deterred — if he acted boldly:

- He could levy the harshest penalty, excommunication, against a dozen or more of the most egregious abuse enabling church officials. (He's done this to no enablers, or predators for that matter.)

- He could insist that every diocese and religious order turn over every record they have about suspected and known abusers to law enforcement.

- Francis could order every prelate on the planet to post on his diocesan website the names of every proven, admitted and credibly accused child molesting cleric. (Imagine how much safer children would be if police, prosecutors, parents and the public knew the identities of these potentially dangerous men.)

- He could demote at least a dozen or more Vatican bureaucrats and four or five dozen bishops who are or have concealed known or suspected child sex crimes and openly denounce them and lay out their complicity. (In recent years, public outrage has forced Francis to take action against a handful of bishops. But he perpetuates a long-standing pontifical pattern of quietly letting an embattled bishop "retire" or "resign," either deceptively citing "health reasons" or saying nothing at all while letting these bad bishops keep their titles and pensions while they live lavishly and attend important church functions and while most of their flock and their colleagues act as though no wrong was done.)

Across the world, there are more than 5,600 bishops, so the handful of prelates who have or may have been removed by Francis pale in comparison with the task still ahead of him. He's done anything but the kind of thorough housekeeping needed to safeguard kids and reassure parishioners.

Within the past few years, lengthy investigations — some by secular authorities, most by church bodies — have put forth stunning estimates of the number of victims in several nations (Portugal 4,800, Australia 4,444, Germany 3,677, France more than 215,000).

With numbers of this magnitude, can anyone deny that Francis needs to take much stronger and bolder steps?

Advertisement

Church officials in these few developed countries have barely and belatedly begun to face the scandal, much less implement corrective measures. Throughout most of the world, when it comes to abuse and cover-up in the church, what few real changes have come about are largely because of external forces and adopted only on local levels.

Ironically, more than 20 years ago, nearly 200 of his bishops moved more boldly against abuse than Francis.

Throughout the 1990s, small groups of us in SNAP, the Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests, met with more than two dozen U.S. prelates, begging for the adoption of a national "zero tolerance" abuse policy. Without exception, they insisted that this couldn't be done, that the U.S. bishops' conference was more of a fraternal group answerable only to the pope, not to one another.

But in Dallas in 2002, these same bishops finally succumbed to public and parishioner pressure and did as we asked. This move — like most of Francis' policies — was more dramatic gesture than effective reform. (It is sporadically followed and there's virtually no sanction for violators.)

U.S. bishops applaud the vote approving a strict national policy to address clergy sexual abuse. The room of bishops all stood to acknowledge the vote at their meeting June 14, 2002, in Dallas. (CNS/Bob Roller)

Still, it's more than Francis has done. Despite his considerable talk, this pope still has not mandated a "one strike and you're out" requirement across the globe. The vast majority of bishops can still keep or even put convicted or admitted molesters on the job in parishes (usually after being sent abroad or far away).

For example, just last month, a commission in Portugal found more than 100 accused child molesting clerics still on the job.

Here in my hometown of St. Louis, Fr. Alex R. Anderson remains a pastor despite having faced five accusers, including one pending civil lawsuit. He's never been suspended for even a day, though the bishops' Charter for the Protection of Children and Young People requires that an alleged predatory cleric be suspended pending a full investigation.

It's horrifying to consider how many boys and girls have been sexually assaulted because this otherwise admirable world leader repeatedly professes to support zero tolerance but can't bring himself to enact and enforce this notion globally.

As so many have pointed out, from the moment he appeared on that balcony in Rome a decade ago, Francis continually surprises his followers, his fellow clerics and indeed the world by breaking the stale and rigid papal mold time and again in so many ways.

But on the central crisis roiling the church, Francis talks a great game while doggedly remaining in the ruts that characterize the rest of the comfortable church hierarchy and that leave children at risk, the corrupt in control and the flock floundering.