Hagia Sophia is seen June 30 in Istanbul. (CNS/Reuters/Murad Sezer)

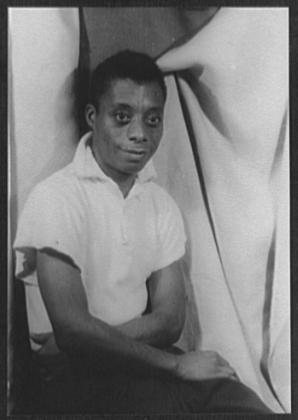

"Portrait of James Baldwin," by photographer Carl Van Vechten, taken Sept. 13, 1955 (Library of Congress)

Few know about James Baldwin's years spent in Turkey. "I can't breathe, I have to look from the outside," he once remarked when asked why in 1961 he began visiting Istanbul on and off for a decade. Turkey offered him a space to escape from the racism and homophobia he experienced in the United States, but also to reflect more deeply on who he was.

He once reminisced about eating lunch with Turkish filmmaker Sedat Pakay and Greek actress Irene Pappas, who commented to Pakay, "Look at those eyes, 400 years of oppression in them."

The Ottoman enslavement of Greeks and Armenians and Mustafa Kemal Atatürk's genocide and expulsion of them in the early 20th century are vastly distinct phenomena from the transatlantic slave trade and Jim Crow laws in the U.S. But both of our countries have constructed myths to conceal these ugly realities that they are founded upon.

"It is, of course, in the very nature of a myth that those who are its victims and, at the same time, its perpetrators, should, by virtue of these two facts, be rendered unable to examine the myth, or even to suspect, much less recognize, that it is a myth which controls and blasts their lives."

Baldwin continues to say in his 1964 essay "Nothing Personal" that this "blindness," this willful forgetfulness of one's history and the injustices committed, is a cause of "spiritual disaster," not only for the oppressed, but even more so for the oppressor.

When I heard the news about Hagia Sophia being converted from a museum to a mosque, I instantly thought back to Baldwin's words. Turkey's insistence on denying the 400 years of enslavement, the millions of lives killed, and suppression of the Orthodox Christian community is a denial of Turkey's identity.

Turkey's culture is a rich tapestry weaving together the threads of the Seljuks and Ottomans, the Greeks, Armenians, and Turks, Christians and Muslims, people of all different shades and skin tones, leaders who have committed heinous atrocities and who have led the country to new heights. To deny any of the complexities and nuances of this history is to blind oneself to the reality of what it means to be Turkish.

I remember my first time visiting Hagia Sophia. I was with my grandfather, who was born in Istanbul to Greek and Armenian parents. This was his first time back in 35 years. He presented his native city to me with pride, tinged with a hint of anguish. He complained to me after our first night there of nightmares of being attacked for being an "infidel."

And yet, Istanbul remains his city. His mixture of Greek, Armenian and Turkish blood, his Orthodox Christian faith, has left its indelible mark on the city, and will continue to do so ... even if the majority of Armenians and Greeks were murdered, and the remainder left along with him in the '50s, and the Christians that make up less than 1% of Istanbul's population — including the ecumenical patriarch — continue to face restrictions.

Turkish police officers walk in front of Hagia Sophia July 11 in Istanbul. (CNS/Reuters/Murad Sezer)

The virtue of leaving Hagia Sophia as a museum is that it allows people to feel that complex mix of emotions — pride and sadness, appreciation and shame — that the space evokes. The Byzantine mosaics and Islamic calligraphy speak to the value of both religions and the ethnic groups that adhered to each, as well as the injustices that have been perpetrated throughout the centuries — not only Muslim against Christian, but also Christian against Muslim and Christian against Christian (our tour guided pointed to a red mark on the wall, claiming that it was the bloody handprint of a Catholic in the Fourth Crusade).

The systemic denial of the Armenian Genocide and expulsion of Christians continues to be a point of contention to this day. I recounted the story of my great grandmother's escape from Izmir to the island of Chios during the expulsion of 1922 to a new Turkish friend I met in college, hoping that sharing this with her could be an opportunity for healing and reconciliation. "There was no genocide," she proclaimed, irritated with my presumption. "It's all propaganda from the American government."

"So then why did my great grandmother see Turkish soldiers raping and mutilating women as she was running to the port?"

"It's not the Turkish government's fault that some soldiers decided to do those things on their own."

Advertisement

I felt pity. Such blindness can hardly be liberating. Thus my concern for those who would be praying the following afternoon in the newly minted mosque. Can one freely commune with God — Allah — while being in denial of reality? Can Muslims and Christians love and dialogue with each other, seek the Mystery of the Divine together, while shielding our faces from the truth?

That Friday at 4 p.m. EST, I attended the Akathist service at my family's Greek Orthodox parish, joined spiritually by other Orthodox, Catholic, and hopefully Muslim communities, to beg God for the gifts of repentance and reconciliation, and of the honesty and courage to embrace reality, to embrace history, in all of its grace and ugliness.

During the service, I thought about Baldwin's words in "Nothing Personal." I thought about the blindness of the slave traders to their own humanity, their own need for love and intimacy, which drove them to dehumanize other human beings, and in the process, dehumanize themselves. It was their insecure attachment to wealth, power and complacency that drove them to perpetuate this lie, this false divide between brothers and sisters, by any means necessary. Baldwin recognizes, however, that this blindness, this affinity for mendacity, is not only an American phenomenon. It's a temptation that humans throughout the world are subject to.

We live by lies. And not only, for example, about race — whatever, by this time, in this country, or, indeed, in the world, this word may mean — but about our very natures. The lie has penetrated to our most private moments, and the most secret chambers of our hearts. Nothing more sinister can happen, in any society, to any people. And when it happens, it means that the people are caught in a kind of vacuum between their present and their past — the romanticized, that is, the maligned past, and the denied and dishonored present. It is a crisis of identity. And in such a crisis, at such a pressure, it becomes absolutely indispensable to discover, or invent — the two words, here, are synonyms — the stranger, the barbarian, who is responsible for our confusion and our pain. Once he is driven out — destroyed — then we can be at peace: those questions will be gone. Of course, those questions never go, but it has always seemed much easier to murder than to change. And this is really the choice with which we are confronted now.

The prayers of the Akathist service brought me back to the roots of this blindness which are as old as the fall. But it also placed me in front of a promise, a glint of hope, that is born from entrusting our fears, sins, and woundedness to the New Adam and Eve.

The news of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan's decision to convert the Kariye Museum (formerly the Holy Savior church) in Chora to a mosque brought me back to Baldwin's words. One who is determined to remain blind to reality, to perpetuate a division between us and them, must continuously strive to eliminate history. I continue to offer my prayer to the Divine Healer of wounds and to his Mother, ever more fervently, and united more deeply in solidarity with all of those whose stories face the threat of erasure from history.

[Stephen Adubato studied moral theology at Seton Hall University and currently teaches religion in New Jersey. He also blogs at Cracks in Postmodernity on the Patheos Catholic Channel.]