(NCR)

On Nov. 1, Pope Francis gave a new mandate to the Pontifical Academy of Theology to "develop" the theological discipline to embody "a culture of dialogue and encounter between different traditions and different disciplines, between different Christian denominations and different religions."

Francis' mandate is particularly telling because it offers a subtle shift from the initial mandate given to the academy when it was founded by Pope Clement XI in 1718, which was to ensure that theology was properly engaged with the realities of the day, especially as history was playing out at the tail end of Christendom. While affirming the vision of his predecessor, Francis sees the need for contemporary theology to reflect responses to the existential questions of the contemporary era.

Francis envisions the need for a paradigm shift, one that locates theology within the "common human experiences" of life in a world saturated with meaning. This approach to doing theology is reflected in the contributions of Fr. Bénézet Bujo, a theologian from the Democratic Republic of Congo, who was a professor of theology at the University of Fribourg, Switzerland, and died Nov. 9 at age 83.

Bujo's theological contributions best reveal how theology can be transdisciplinary and be a dialogical partner with other disciplines and traditions. Grounded in deliberate epistemic encounters with Western theological and philosophical voices that include St. Thomas Aquinas and Dominican Fr. Edward Schillebeeckx, Jürgen Habermas and Karl-Otto Apel, Bujo offered his own contributions to the global theo-ethical discourse from the locus of his concrete African world. In doing this, Bujo gave a systematization of African theological imagination.

For Bénézet Bujo, African theology was a theology of encounters that must speak first to Africans while also being in dialogue with the rest of the world.

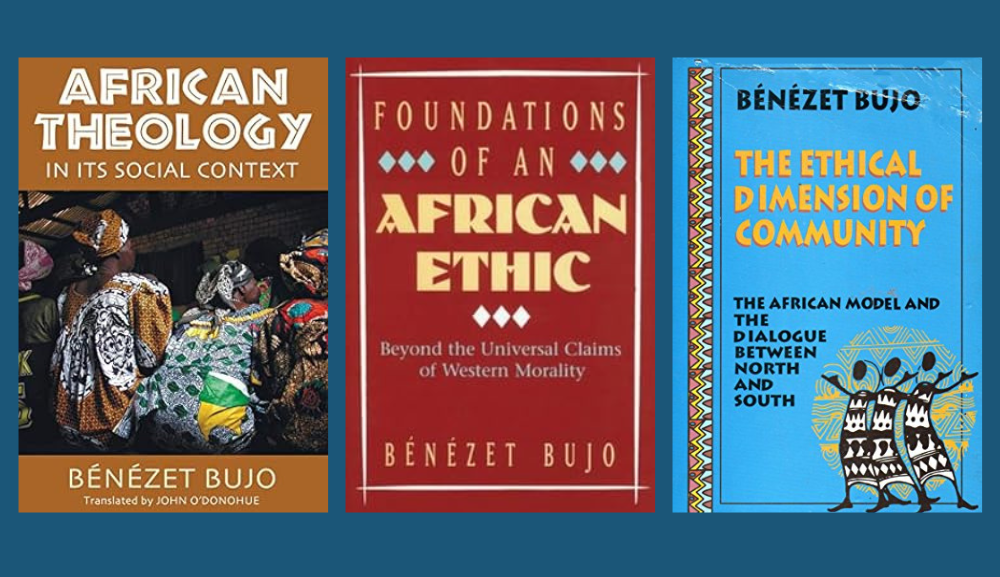

For Bujo, African theology is a theology that emanates from and speaks to the realities of the social contexts of the African people. He argued for a deliberate retrieval of an African consciousness. Hence, in his 1992 book African Theology in Its Social Context, Bujo shed light on the commonality that defines the Black world and the need for African theology to embody African existential experiences.

The role of the theologian in the African world is to be the prophetic voice that upholds African images of life while shedding light on the vices of death in society and church. African theology is beyond the simplistic adoption of African images. It is a theology that is inherently attuned to an African consciousness. Such consciousness should be able to speak truth to the current realities playing out in neocolonial Africa, while also grounding itself in a rich understanding of the continuum of Africa's historical existence.

Bujo was conscious of the current debates playing out in the continent among ethicists, theologians and other scholars on whether the solution to Africa's problems resides in the retrieval of the past (turning backwards) or focusing only on the current (ignoring the past). For Bujo, these were false movements that would be unable to birth enduring solutions.

Without the knowledge of the past, the prophetic witness of theology in contemporary Africa will itself be unattainable. To dream of a future for Africa that builds on the narratives and praxes of life playing out in the present means that African theology ought to embody a prophetic turn that is centered on a kairos witness to God's liberating truth. In other words, for Bujo, African theology was a theology of encounters that must speak first to Africans while also being in dialogue with the rest of the world. It is a bridge where life ought to be experienced abundantly by all.

Two African relational concepts radically define the contributions of Bujo to the disciplines of African theology and African social ethics: palaver and ubuntu.

As I have written previously in the Journal of Catholic Social Thought, palaver "is about holding in place all the tensions that are playing out in society and also linking social harmony to cosmological consciousness." Ubuntu, as one encyclopedia states, "embodies all those virtues that maintain harmony and the spirit of sharing among the members of a society. It implies an appreciation of traditional beliefs, and a constant awareness that an individual's actions today are a reflection on the past, and will have far-reaching consequences for the future." In other words, it serves as a prophetic reminder to an African to live always as witness to the shared values of the community.

While many who have attempted to retrieve the rich world that opens up in the domain of ubuntu tend to focus on a shallow understanding of the concept, Bujo, in his 2001 book Foundations of an African Ethic: Beyond the Universal Claims of Western Morality, sheds light on the link between palaver and ubuntu as the possibility for realizing the existential horizon of fellowship that ubuntu instantiates.

Advertisement

In other words, without palaver, there can be no ubuntu. Thus, ubuntu is itself a relational philosophy of difference that becomes the locus of abundant life only if the praxis of palaver is embraced by those who embody differences — be they epistemic, religious, cultural, gender, linguistic or territorial. Palaver is the ritualization of dialogues of encounter that prioritize the expressions of difference while holding in place the belief that all beings participate in the oneness of life — a belief that must never be abandoned even when difference is a saturated reality being experienced by the parties involved in the dialogues of encounter.

The holding in place of the oneness of life and the turn to encounter even in difference is what makes the fellowship of ubuntu important to be realized — because through the insistence on dialogue, all parties begin to see what they share in common.

Bujo, in his 1998 book The Ethical Dimension of Community: The African Model and Dialogue between North and South, offered a critique of western notions of subjectivity which tend to be a turn away from encounter. His theological approach to African theology was not just in the domain of deconstruction. He offered a robust constructive African theo-ethical anthropology. For him, to speak of the human person was to speak of both the communitarian and the individual dimensions.

The community is the locus where the fecundity of life is experienced by the individual. The individual is a palaver being that embodies existential difference. A symbiotic relationship of life exists between the community and the individual. It is from this locus of symbiotic consciousness that Bujo offered ways that Catholic theology ought to take seriously insights from Africa that tend to uphold visions of surplus, which affirm a both/and approach to theological issues against the dominant dualism in Western consciousness.

Finally, though Bujo has joined the community of ancestors who surround Christ, the proto-ancestor in the heavenly village, his role as an African theologian and social ethicist serves as a beacon of inspiration for emerging African theologians as they attempt to do theology from their locus of existence.

Emulating the approach of Bujo allows for an African theology that has an African palaver being, an African face, an African voice, an African heart, an African logic, an African hospitality toward otherness and an African praxis of life lived out in the domain of ubuntu consciousness. If this approach is taken seriously not just by African theologians, but also by theologians who engage the African world, then Francis' vision of doing theology in the 21st century that reflects the realities of social life would be embraced fully.