The Church of the Nativity, New York City, pictured Dec. 4, 2018, held its last Mass in 2015. It was the parish attended by social activist and sainthood candidate Dorothy Day and was sold in March 2020. (CNS/Gregory A. Shemitz)

Dorothy Day was set on Earth with a rumble in her soul. About 5 a.m. April 18, 1906, Dorothy, age 8, and her parents and three siblings were awakened in Oakland, California. "The earth became a sea," Dorothy would write years later describing the night an earthquake destroyed neighboring San Francisco, leaving cracks in the family's ceiling, toppling its chimney, smashing its dishes, glassware and chandelier.

From outside their barely habitable dwelling, the Days could see the smoke of blazes across the Bay. They were grateful they'd recently left San Francisco. Soon they moved to Chicago.

Seventy-three years later, Dorothy would note in her Jan. 30, 1979, diary entry the mini earthquake that had rumbled through Brooklyn (her birthplace in 1897), Staten Island (her home over many years), and nearby New Jersey and Westchester. Why not Manhattan, she wondered.

"Unimaginable to think of those fantastic World Trade Towers swaying from a sudden jarring of what we have come to think of as solid earth beneath our feet," this constant city walker mused in her diary.

Was the earth ever solid beneath the worn soles of Dorothy Day's mostly second-hand shoes? By the time she inscribed these jottings, she had only months to live and was spending them at Maryhouse, the recently opened Catholic Worker home for women on East Third Street in Lower Manhattan. It was here that Dorothy suffered a mild heart attack in September 1976, a more serious one in 1977 and death in her bed on Nov. 29, 1980, three weeks after her 83rd birthday.

For 40 years now the Catholic Church, New York City, the hungry and homeless, the poor and walking wounded — indeed the whole world — have done without the tall angular woman with the high cheekbones and white, braided hair.

Day — who made hundreds of appearances, traveling mostly by bus, endured an aversion to public speaking but saw it as necessary — is no more. The writer of hundreds of columns and articles in the monthly Catholic Worker, which she founded in 1933, and thousands of letters — so many that at times her fingers, hand and arm went numb — no longer fills any column inches or mail boxes.

Advertisement

But Dorothy Day's influence abides. So much so that some have seen her as the seminal Catholic figure across the 20th century. Her cause for sainthood has been initiated even in the wake of a lifetime that included allegiance to the Communist party, affairs, an abortion, divorce, an out-of-wedlock birth, two suicide attempts and a youth colored by excessive drinking, chain-smoking and a lurid vocabulary, as well as estrangement from her father and older brothers.

Add to this dozens of arrests for protests and civil disobedience — the last at a United Farm Workers demonstration in California when she was 75. Day spent days and weeks inside jails and detention centers. FBI agents kept tabs on her over 30 years, collecting her writings on anarchy, capitalism and in opposition to the draft, to wars and nuclear weapons. Her early columns opposing anti-Semitism abroad and segregation at home were also compiled by the bureau as was her testimony against conscription before a Congressional committee.

Her biographical details notwithstanding, Pope Francis told his Washington audience and millions of TV viewers during his September 2015 address to Congress that Dorothy Day and Trappist Monk Thomas Merton were for him exemplary Americans. Put them in the pantheon with Abraham Lincoln and Martin Luther King, the pope's other picks, and these two Catholic figures, who knew each other through correspondence, form a twin set of sin and repentance.

Indeed, Day's conversion to Catholicism — like Merton's — was a roundabout journey, though one she seemed always headed toward. "Haunted by God," was a phrase she used frequently to describe her soul's strivings. Within days of her only child's birth, she insisted on having Tamar baptized a Catholic, though the child's father, Forster Batterham, vehemently opposed it, putting religion even lower on his "dislikes" list than marriage or child-rearing.

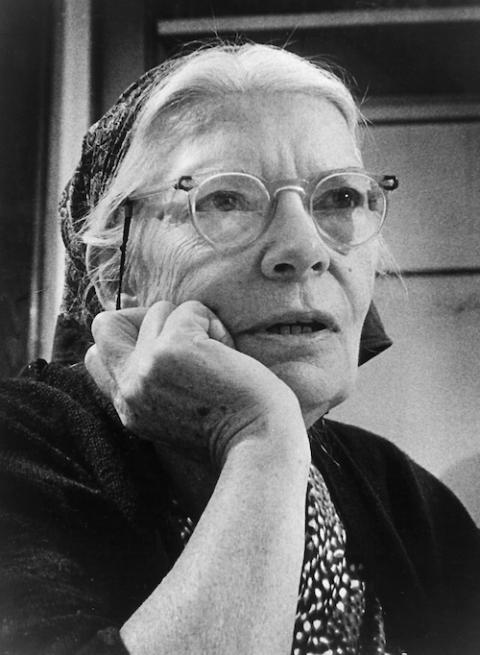

Dorothy Day, co-founder of the Catholic Worker movement, pictured in an undated photo (CNS/Courtesy of the Milwaukee Journal)

Soon the God-haunted Dorothy was herself baptized, having solicited the help of a local nun and four priests she had met in New York and on Staten Island. The priests treated her compassionately, encouraging her to continue to work as a freelance journalist to support her family. For the good of her daughter, they advised her not to forsake her common-law marriage. Who knows what would have become of convert Dorothy had she met a stricter band of clerics

Although Day's baptism took place four days after Christmas in 1927 — four days after she had ordered Batterham out of her house — she found little joy in her new circumstances. Yes, she loved the church's liturgy and learning about its dogma, history and saints, but she had no family or friends who rejoiced in her conversion and no lover with whom to share either the joy of union or of parenting.

All that would change late in 1932, when Day travelled to Washington as a freelance journalist to cover the National Hunger March, a demonstration partly organized by communists. Some 3,000 unemployed men spent two days and nights on the streets of the capital waiting for a permit to march in order to call attention to their need for government relief. As committed as she was to the cause of social justice for the men, Day made a detour to the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception while in Washington and asked God to show her how to become more of an activist in alleviating the suffering she saw all about her in the wake of the Depression.

Returned to New York the next day, Day found a slovenly dressed man on her doorsteps. He insisted on seeing her. The man was Peter Maurin, the picture of poverty, with the patter of philosophy emerging from his often difficult-to-understand Frenchman's accent. Still Maurin's talk enticed Day, especially his questions about human suffering, his knowledge of Catholicism and his belief in education as the lever for all social change. A journalist for several years, Day grew attracted to Maurin's plans for a Catholic newspaper that would address pertinent issues for the church and the world. Later she would date her real conversion to that initial meeting with Maurin: Dec. 9, 1932, almost three years* after her baptism.

For the next 16 years — until Maurin's death — the pair would open houses of hospitality to shelter the homeless in dozens of U.S. cities. They would set up bread lines to feed up to 1,500 unemployed men daily, provide used clothing for them and their families, and launch the monthly Catholic Worker, selling it on the street for a penny a copy. The newspaper, which dealt with issues of the day in strong opinion pieces and bold drawings, reached a peak readership of 190,000. Today it counts some 25,000 subscribers and publishes seven issues annually.

Long before the church proclaimed its preferential option for the poor, Day and Maurin were living this precept with their outreach to the city's most desolate and despondent souls. While the pair lived and taught voluntary poverty, Day's diaries showed just how difficult was this way of life. Not only were their hospitality houses crawling with lice and bedbugs, they also housed the slothful, filthy, alcoholics, the mentally deranged, a few addicts and many who turned aggressive, even violent.

Day suffered from constant headaches, fatigue and worries over writing deadlines and mounting bills. Besides the paper and houses of hospitality, she also maintained a number of farms over the years.

Still, she saw Christ in the face of each and every inhabitant and unemployed person whether in the city or on the land. How to live such a life? That is a question this writer has pondered years after meeting Day twice in the 1960s, and once again today, 40 years after her death. To go face-to-face, elbow-to-elbow with the very poorest, the unhinged and the combative is much harder than writing a check, donating to a food pantry or praying for the poor, who — like water — slip through our hands.

Day showed us a way toward holiness. She recognized the route that sin had taken her and chose to destroy many of her diaries from the early decades of her life; the later ones she allowed to be opened 25 years after her death. In some sense, she lived the last four decades of her life in reparation for the excesses of the first four, using the sacrament of penance frequently. Her route to sanctity began with morning Mass almost daily, praying the rosary each evening, reciting Compline and reading Scripture and the Little Office, which she was fond of doing on the train or aboard the hundreds of buses she took across the nation. She encouraged these practices among the guests in all the houses of hospitality.

Forty years on, the most influential lay person in the history of American Catholicism may not be a household name or even well known in every Catholic institution, but some 150 houses of hospitality carry on in her wake, in this nation and several others. They shelter scores of men and women seeking to live simple and serene Gospel-based lives. Many are pacifists, some continue to write and protest against weapons systems, climate abuses and excesses of capitalism.

Day continues to find followers among the young, her favorite generation during much of her life. Many who knew her have written of her unique ability to discern a person's vocation, seeing capabilities in them of which they were unaware.

Not surprisingly, America's most radical Catholic has had service projects, buildings, lecture series, seminars and symposiums named after her at Catholic, Baptist and secular universities. Forty years after her departure and 123 since her birth, the rumble in Dorothy Day's soul is still seismic.

[Patricia Lefevere is a longtime NCR contributor.]

*This story has been updated with the correct date.