Magnetic force field around two bar magnets, visualized with iron filings scattered on the paper. (Dreamstime/Brian Maudsley)

My in-laws are farmers and live on 200 acres in a quiet part of Northern California. Although there are very few "destinations" near them — olive tasting is a notable exception — I have made the Trappist monastery at Vina a must on Sundays.

I clearly harbored naive assumptions about monks. I did not give them proper credit for their connectedness to the outside world, as I was very surprised by how tuned in their petitions were during that first Mass with them. From local to global, the prayers were concrete. For example, they did not just ask for "an end to hunger"; they prayed for structural reform, calling the World Bank and International Monetary Fund to justice.

After they offered their own petitions, they opened it up to the community. Brave.

People prayed for things more immediate to their lives, such as a sick uncle about to undergo surgery. Then a woman in her 30s with a French accent prayed for "the conversion of the hearts of terrorists." We responded, "Lord, hear our prayer." But, someone might contend, why pray for terrorists when you can pray for Americans? The next prayer was from a woman in her 60s wearing an American flag pin on her chest, "For the swift and total victory of American troops in the Middle East, we pray." "Lord, hear our prayer."

I admit I don't know whether or not the victory prayer was motivated by the first woman's prayer, but given the polarization we're facing today, it is a viable explanation. And with polarity comes suspicion in situations of ambiguity; the second prayer for troops clears up any ideas that the first prayer extends charity to terrorists. Or, worse, it was a rebuttal. It is a sad time when it is difficult to pray together, even during Mass.

I'm sure many readers have been in the "dueling petitions" scenario. And polarization manifests in our churches in other ways. There is the "I disagree!" shouted from the back of the church during the homily (but more often mumbled from one pew back). There's the aggressive discussion at the ministry booth as to whether the LGBTQ ministry "belongs." There is being told that one cannot collect signatures to end the death penalty after Mass. The polarity in our parishes mirrors the polarity in the wider society.

People say our society is getting increasingly polarized, but is it true? We have heard the rhetoric and the vitriol, but is this just what improves ratings? If it bleeds, it leads? Is this so-called "culture war" really just fought among leaders and the media or is polarization a fact that touches the rest of us? Further, is this polarization also happening among American Catholics? If so, how can we heal? Lots of questions — let's look at some answers.

Polarization in the U.S.

If we look to Pew data, it appears that we are becoming more polarized. This graph illustrates that the ideological gap between Republicans and Democrats is growing. In 2014, 92 percent of Republicans were more conservative than the median Democrat and 94 percent of Democrats were more liberal than the median Republican. Compare this to 64 percent of Republicans and 70 percent of Democrats in 1994. Further, Pew data showed that more than one-quarter (27 percent) of Democrats "see the Republican party as a threat to the nation's well-being" and over one-third (36 percent) of Republicans say the same of Democrats.

As if this growing social polarization were not enough, the personal animosity we harbor toward those not of our political persuasion is serious. When Gallup asked Americans in 1958 if they had a daughter of marriageable age, what would they like the political identity of the groom to be, 18 percent responded Democrat, 10 percent Republican and 72 percent did not care. When this question was asked in 2016 by another researcher, Lynn Vavreck (who also included "son" in the question), found that 28 percent preferred a Democrat, 27 percent said Republican and only 45 percent did not care. Political parties are the new Montague and Capulet.

A voter carries his ballot behind a voting booth at a polling station in the Bronx section of New York City during the 2016 U.S. presidential election. (CNS/Saul Martinez, Reuters)

Another study shows that people do not rate their political identity as very important to their overall identity. People are much more likely to say that their family status (e.g., husband, mother), religion, gender, age, occupation, nationality, race and region of the country are more important than their politics; in fact, the only thing political identity outranks is social class. However, the authors note that although political identity itself is not highly ranked, these more important identities — like gender, religion and family status — tend to correlate with a political identity. It is a matter of "identity politics." So while a male, Christian Southerner and a black, urban mother both may not rank their political identity as high, their other aspects that they do rank high are wrapped up in their politics. However you roll the dice, politics matters.

Catholic division in the U.S. experience

So if our country is polarized, what about our church? Is it any better? Is it any worse? An important thing to note about Catholicism in the United States is that there was always some sort of division that shaped the Catholic landscape. To look closely at one instance, some of the first Catholics to arrive in the United States were from England and they thought very highly of the democratic principles that animated the country. When they saw the congregationalism of many U.S. churches, they argued for a similar lay trustee system. In this, the laypeople would have a strong say in the governing of the parish.

Catholic historian Jay Dolan discusses lay trustees in The American Catholic Experience: A History from Colonial Times to the Present. Depending upon the bishop, lay boards held different degrees of power. Sometimes a bishop would move a disliked pastor to another parish at the behest of the board. In other cases the laity did not get their wishes and, when they were especially defiant, the bishop would place the parish under interdict and excommunicate the parishioners. Conflicts could last as long as 20 years and sometimes even turned violent, with one exceptionally heated conflict ending in a riot, leaving roughly 200 parishioners injured.

In addition to the conflicts over power that early English-born Catholics experienced, there was the fierce hostility between Catholic ethnic groups in the 1800s. In the 1920s and '30s, there was conflict between upper-class Catholics and the rest of the faithful, when social reform was placed more prominently on the American Catholic agenda. But all of these previous lines of division were in-house issues; they weren't mirrored in the wider culture more broadly.

As sociologist Will Herberg notes in his 1955 classic Protestant, Catholic, Jew: An Essay in American Religious Sociology, wider social divisions were typically based along lines of faith. How a person voted, whether or not they went to college, how many children they had, whether they lived in an urban or rural context and more could be predicted by whether one belonged to the Protestant, Catholic or Jewish faith. Catholics had their own divisions among themselves, yet there were social divisions in the wider society that emphasized Catholic commonality when examined from the outside.

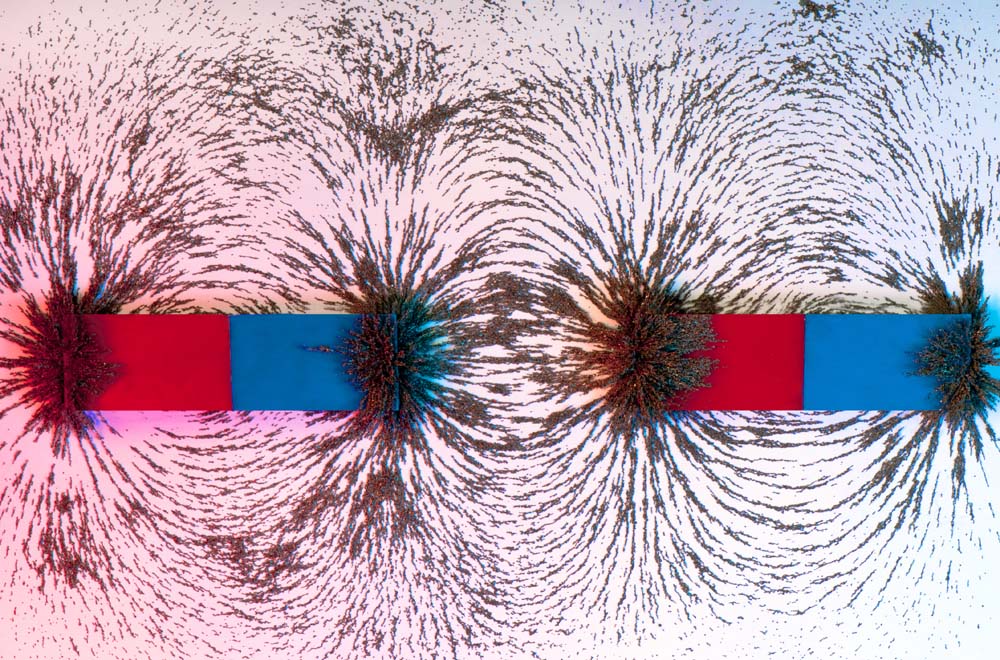

You might have noticed in the foregoing section that I have discussed "conflict" and "division," but not "polarization." As Holly Taylor Coolman discusses in her essay in Polarization in the US Catholic Church: Naming the Wounds, Beginning to Heal, polarization and conflict are not the same thing. Conflict is a problem with positions or ideas that necessarily gather people to resolve whatever is at the root of the dissonance; they depend upon what they share in common to navigate their differences. Polarization is a matter of two opposing (rather than different) ideas organizing the whole of an existence; think about the pattern iron filings form as they are arranged by the two poles of a magnet. When people are polarized, they define themselves against the other pole. The poles determine everything. In a situation of conflict, it is commonality that organizes debate. In one of polarization, difference organizes it. In fact, polarization often prevents the healthy conflict groups need in order to move past what divides them. Although conflict can be healthy, polarization never is.

Which brings us to the differences among today's Catholics as we compare them to the past. Previously, the divisions were a "Catholic problem." When Italian Catholics were frustrated that their traditions were being looked down upon by their coreligionists, at least when they left their ethnic ghetto they were reminded how much they shared with other Catholics; they were, in fact, very different from non-Catholics. Now the axis is political and runs not just through our parish or diocese, but through the whole of American life. From divisions of Protestant, Catholic or Jewish, we are now, as Catholics, grouped into a liberal or conservative binary, a binary that is reinforced in our jobs, leisure, home life, political commitments and more.

Factors for a polarized Catholicism

What did the transition from the tripartite society into one of progressives and traditionalists look like for Catholics? While there were many significant factors that came together in the 1940s through the 1960s, many scholars point to the importance of the GI Bill. Catholics had a modest, often working class background before World War II. With the high level of Catholic participation in the war, many came back to earn college degrees. This led to a Catholicism that was solidly middle class and rising. Many left their ethnic neighborhoods for homes in the suburbs. New ideas of what was "proper womanhood" were put on the table. Owing to these and others, religious differences became less significant and the larger worldviews of being either liberal or conservative mattered most for how one voted, vacationed, attended church (or not), worked and others.

I want to lift up two important factors that continue to increase and sustain polarization among American Catholics: an increasing sense of individual moral authority and parish choice. Beginning with individual moral authority, as William D'Antonio and his team demonstrate in American Catholics in Transition, Catholics are increasingly saying that the final moral authority on an issue is not the bishops or the bishops and laity together, but only with the individual involved. For example, in 1987, 31 percent of Catholics said that the moral authority concerning divorce and remarriage lies with individuals alone. By 2011, that figure rose to 47 percent. As Phillip Hammond discusses in Religion and Personal Autonomy: The Third Disestablishment in America, this individualist shift is present even in more conservative traditions. With a greater sense of their own moral authority, both progressive and conservative Catholics can feel more at home in political identities as Republicans (eschewing teaching on the death penalty or government assistance for those in poverty) or Democrats (minimizing teaching on abortion or assisted suicide).

Parish choice also feeds into polarization. Sociologist Tricia Bruce's Parish and Place: Making Room for Diversity in the American Catholic Church examines the recent increase in personal parishes, that is, parishes canonically designated for a particular population (e.g., Vietnamese Catholics) rather than a particular territory. While many personal parishes serve ethnic groups, they increasingly serve Catholics desiring a parish that celebrates the Latin Mass or places the social mission of the church at its center. People are choosing parishes based on identity. These personal parishes can isolate — or contain, depending on the perspective — Catholics on the ideological margins. This makes parishes more homogenous, leaving Catholics with parishes that act as ideological echo chambers. Let's conclude by noting this is not just a personal parish issue; 30 percent of Catholics leave their designated parish for a parish of their preference, up from 15 percent since the Notre Dame Study of Catholic Parish Life in the 1980s. What happens in personal parishes is a window into parish life more broadly in this time of increased parish choice.

Polarization in elections

At one time in the United States, there was a clear "Catholic vote" and it was solidly Democratic. Since the 1950s, with the exception of the election of John F. Kennedy, it has gradually moved to the center, with this chart from the Pew Research Center illustrating that Catholics demonstrate a fairly even split between the two parties in the most recent midterm elections. In his essay in American Catholics and Civic Engagement, journalist E.J. Dionne Jr. argues that this indicates that there is no longer a Catholic voting bloc. I would disagree. And it is a twist that complicates — and exacerbates — the polarization narrative. We have two significant Catholic voting blocs. The first is more Republican and white. The second is more Democrat and Latino.

As I discuss in more depth elsewhere, many white Catholics vote according to their other demographic characteristics (race, income, age, education), looking very similar to mainline Protestants. These groups both tend to be whiter, older, wealthier and better educated than the average American and tend to lean Republican (but are not strongly Republican as white Evangelicals are). Latino Catholic voting patterns appear to be shaped more by faith; Latino Catholics vote much more strongly Democratic than Latino Evangelicals (there are not significant numbers of mainline Latinos and so Catholic/Evangelical is the better comparison). So Catholic political differences can be magnified by ethnic differences. Further, political commitments — for example, to immigration issues — can be felt as ethnic tension.

We need to grow charity in ourselves, in our parishes and in our world. Charity will help to rebuild the personal and social trust that has slowly eroded.

Visions for a post-polarized church

Clearly there are formidable challenges to moving toward a more unified church. The way to heal this is to end polarization qua polarization, shifting it into political diversity. In this way, we can transform what we are experiencing as a weakness into a strength, a move toward appreciating what Michele Dillon calls the "interpretive diversity" of our faith in her Postsecular Catholicism: Revelance and Renewal. Rather than having poles and opposition organizing American Catholic political discourse, we can listen to the ways Catholics of varying political stripes use both their experiences and church teaching to navigate the vagaries of our complex social world. In this way, we can move from a sense of derision to interdependence; we'll see the value in perspectives that differ from our own and use these to move toward a common ground rooted in our faith. Here are six things I'd suggest for getting there.

Building relationships. We aren't doing too well on the relationship front. Robert Putnam, a sociologist of social capital, writes in Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community that when Americans were asked how many close friends they had in 1985, the average number was three, with the most common answer being two. By 2004, the average number of close friends fell to two and the most common response was zero. Zero. We've lost our social embeddedness. Strengthening our interpersonal connections and trust may help our sense of social trust, as well.

Being uncomfortable. However, just strengthening our interpersonal relationships alone could exacerbate polarization. As I said above, we tend to socialize with others like ourselves, be it according to politics, race, age, income and more. Try also to be around those who are different from you, crossing social boundaries when the opportunities arise. The more you are around those with different experiences, the more you will hear different perspectives. Hearing those new perspectives from friends and acquaintances will make you more empathic and understanding of strangers whose opinions might diverge from your own.

Starting with what is held in common. After we strengthen our relationships and add more diverse connections to these we are ready to begin productive conversations. Whether these conversations are informal between two people or carefully coordinated at a parish or diocesan level, they need to begin with what the parties have in common. These commonalities might be more general — a sacramental vision of the world — or more specific — a commitment to lower abortion rates. Imagine if a small group of ideologically diverse people at a parish led a committee that would constantly guide the parish back to the shared mission whenever events began to rock the community. Making explicit what everyone has in common allows for everyone to regroup and go back to what is foundational when disagreements arise.

Recognizing the differences between disagreeing with principles and disagreeing with the prudential application of those principles. Our conversations will have disagreement. Disagreements can be incredibly productive both for better understanding another perspective as well as for coming up with effective solutions. It is critical in these discussions to know exactly what we are disagreeing about. For example, in a discussion about how a parish might help reduce the local abortion rates, some might propose political efforts to criminalize abortion, while others may find that inappropriate. Further conversation will, I believe, reveal that it is a disagreement over means, and not a disagreement over the dignity of the human person. Encountering disagreements with goodwill will help illuminate the true nature of the conflict and keep conversation centered on the common project.

Dialoguing rather than debating. Too often we debate. There is nothing wrong with a good-natured sparring of ideas. But debates have sides; one side wins and the other loses. For a church in need of healing, debate is not an appropriate method. We need to opt for dialogue. People dialoguing hold their desired outcomes loosely, believing there is more wisdom in the room than their own. Dialogue helps us to understand a different perspective, even while we don't agree with it. We will come away with a better sense of the concerns and discernment of others. Dialogue emphasizes process and allows for loose ends.

Care. Really. If we do everything else well, but ultimately don't care, there is slim chance our efforts will bear fruit. Belittling others or otherwise getting snarky undermines any preceding work. Holding tight to a personal, rather than a shared, agenda will derail the project. Being invested in one another as people and as co-creators as well as working together in great hope, faith and imagination are critical to healing. "Losing" with humility — acknowledging the possibility that the Holy Spirit can work in ways beyond our comprehension — helps us to maintain communion when we are disappointed with an outcome.

In short, to heal our polarization we need charity. We need to grow charity in ourselves, in our parishes and in our world. Charity will help to rebuild the personal and social trust that has slowly eroded. It will take hard work, a lot of patience, an anticipation of setbacks and a long-term vision. Ultimately, charity will move us from one another's throats to one another's hearts. Let's roll up our sleeves and begin to breathe easy and love deeply.

[Maureen K. Day is an assistant professor at the Franciscan School of Theology. She is the editor of Young Adult American Catholics: Explaining Vocation in Their Own Words.]

Advertisement