Drawing of Woodstock College in Woodstock, Maryland, in 1871 (Wikimedia Commons/Jesuit Archives)

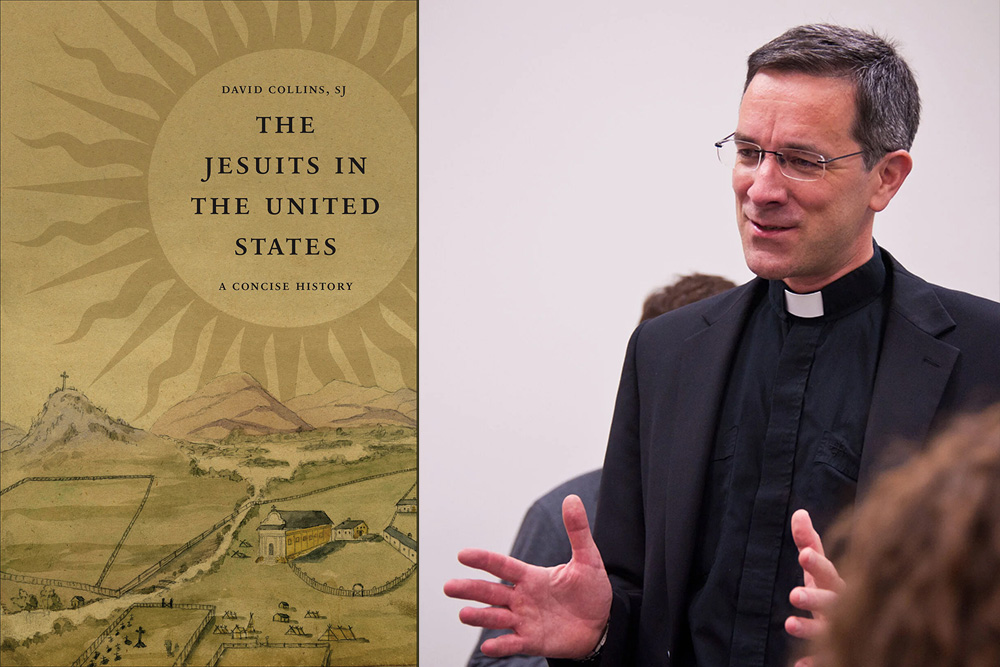

Monday, I started my review of Jesuit Fr. David Collins' wonderful new book, The Jesuits in the United States: A Concise History. Today, we will pick up where we left off, in the early 19th century, as the suppression of the Society of Jesus is about to come to an end.

With the abdication and exile of Napoleon, Pope Pius VII, so long the emperor's prisoner, emerged triumphant and he was quick to restore the Society of Jesus throughout the world. Alas, many European monarchs were still hostile to the order, and they found ways to harass and persecute them.

Europe's loss was America's gain, and Collins looks at the influx of Belgian, Italian, German and French Jesuits who came to this country in the 19th century. The numbers tell the tale. Between 1611 and 1773, fewer than 200 Jesuits had toiled in upper North America. By the end of the 19th century, there were 2,600 Jesuits serving in the United States.

Collins acknowledges the prejudices they faced. "I do not like the late resurrection of the Jesuits," John Adams wrote to Thomas Jefferson in 1816. "Shall we not have swarms of them here, in as many shapes and disguises as ever a king of Gypsies." He continued that if "any congregation of men could merit eternal perdition on earth or in hell ... it is this company of Loyola."

Nonetheless, the religious liberty in the young republic that the Unitarian Adams and deist Jefferson helped found was better than what the Jesuits left behind.

The cover of The Jesuits in the United States: A Concise History, and author Jesuit Fr. David Collins (Georgetown University)

Collins traces the different developments. The Belgians, at the invitation of Bishop Louis DuBourg of Louisiana and the Two Floridas, came to St. Louis and founded a school. From there, they spread north along the Mississippi River and out into the northwest. They founded schools that would become Xavier University in Cincinnati, Loyola University in Chicago, Marquette University in Milwaukee and Creighton University in Omaha, Nebraska.

The Italian Jesuits at first bolstered the ranks of the Maryland Province, with Neapolitan Jesuits founding the legendary Woodstock College. They were exceedingly conservative and here Collins can only hint at the contradictions around which they needed to skate.

"When [Pope] Leo [XIII] condemned Americanism, a set of largely stylized ideas supportive of the separation of church and state and the freedom of individual conscience in matters of religion, the theologians at Woodstock rallied in his support," Collins observes. "At the same time, the US Jesuits gave little sign of abandoning their alliance with the liberal ideals that had welcomed them in the colonial period and propped open the Republic's doors to Catholics, however reluctantly, as the European variety of liberalism persecuted them."

Collins, too, is skating a bit here. Other Jesuits headed West, founding what would become Santa Clara University and the University of San Francisco in California, and Gonzaga University in Spokane, Washington.

An influx of French Jesuits followed the 1830 revolution in the mother country. Bishop John Hughes' desire to strengthen the college he had begun in New York City coincided with the desire of the Jesuit visitor Clement Boulanger to extract the order from a failing mission in Kentucky: Hughes deeded St. John's College, later Fordham University, to the order.

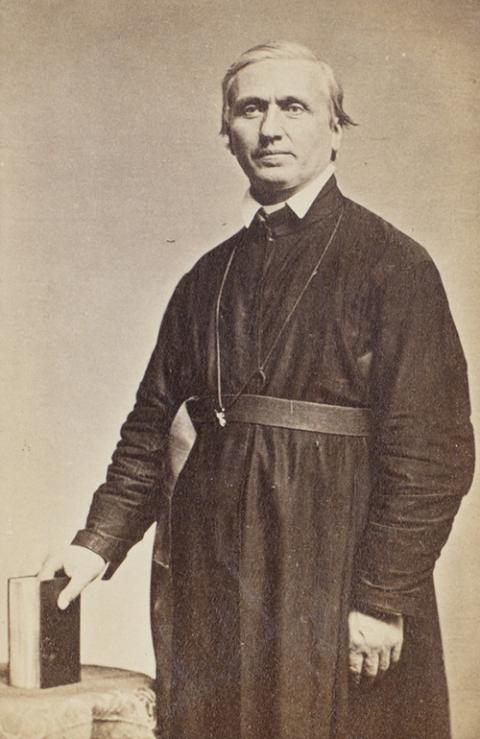

Jesuit Fr. Johannes Bapst, circa 1863 (Wikimedia Commons/Boston College Libraries)

In Maine, Jesuit Johannes Bapst was tarred and feathered in 1854 for opposing the use of the King James Bible with Catholic students in the public schools, or as the local Protestant elite said, "reducing the free-born Americans to Rome's galling yoke." A disagreement with the bishop of Portland led the Jesuits to leave the state and Bapst moved to Boston and became the first president of Boston College.

The German Jesuit mission "was distinctive from the others by being least worried about working within a clearly defined geographical area." Collins notes that the famous Spanish Jesuit missionary in Sonora, Eusebio Kino, was actually born in the German empire and that "Kino" was the Spanish version of his family name, Kuhn. He studied at Freiburg, Ingolstadt and Landsberg before heading to Mexico.

In the mid-19th century, German Jesuits were deployed in many areas, as bishops sought help meeting the pastoral needs of German-speaking immigrants. So, for example, arriving in Buffalo, New York, they helped the local bishop staff parishes, but also founded Canisius College.

This record of growth and success throughout the 19th century was followed by what Collins terms a "coming of age" for the U.S. Jesuits in the early 20th century.

In 1915, the Jesuit provinces organized themselves into assistancies, "a group of provinces that work together on common projects and that the superior general handles as a unit in many matters." This echoed the earlier removal of the church in the United States from the jurisdiction of the Roman dicastery for mission territories, the Propaganda Fide.

As the church and the society became more robustly engaged with the ambient culture, leaders needed strategies for the "careful navigation between the often-incompatible expectations of Roman authorities, the dominant American Protestant elite, and the diverse American Catholic population itself," Collins writes.

Advertisement

By the middle of the century, the number of provinces in the U.S. had increased to 10 and three houses of study had been added to the one at Woodstock. Collins notes that all three were in rural areas, not because of any lasting influence of the Maryland plantation tradition but, instead, reflecting "the notion held more broadly in the Church that the training of priests ought to be at some remove from the seeming decadence and distractions of the city."

The Jesuits continued to mount missions to Indigenous peoples, but their primary focus was always education. Collins ably discusses the pressure to abandon the classical Ratio Studiorum in favor of more modern pedagogical methods, a debate that was somewhat forced on the order because of changes in non-Catholic higher education.

In 1893, Harvard University Law School issued a list of 102 schools whose graduates were assumed to have the qualifications for admissions, but not a single Catholic school was on the list. Five years later, a survey revealed that most Catholic students attended non-Catholic colleges, another wake-up call for reform.

Jesuit Fr. Terence Shealy (Fordham University Libraries)

Collins traces the ways the Jesuits expanded their pastoral outreach with both parish missions and lay retreats. I was delighted to find mention of Fr. Terence Shealy, an early labor priest whose retreats addressed pressing issues through the means of Ignatius' Spiritual Exercises. Eventually, 17 Jesuit retreat houses were offering 500 retreats attended by 13,000 participants each year.

It is sad to think of how many Jesuit institutions in our own day seem indifferent or sometimes hostile to labor rights. Georgetown University's Kalmanovitz Initiative is a happy exception to the rule.

Consideration of the "social question" and the "race question" close out the chapter, and, as in the rest of the book, Collins sums up a complicated, but fascinating, history very well, and points the reader to additional materials should they want to learn more. The bibliographies at the end of each chapter are a great resource for everyone.

Readers of this column will especially enjoy Collins' discussion of Msgr. John A. Ryan's A Catechism of the Social Question and of Jesuit Fr. John LaFarge's pioneering work combating racism and antisemitism.

The final chapter spans the years 1960-2000. It is ably done but suffers from proximity to our own time.

For example, Collins writes of the ongoing changes in higher education and specifically of the 1967 Land O'Lakes statement, which asserted the independence of scholarship from hierarchic interference: "Land O'Lakes' ambitious vision created the springboard from which Catholic research universities, including several Jesuit ones, emerged in the last quarter of the century."

That is true, and the challenges it was meant to address remain "vexing" as Collins writes. It is too soon to assess the long-term ramifications of that statement's influence.

Still, Collins offers a concise account of the decline in vocations, the changes in internal formation and organization adopted by the society, and its renewed involvement in ecumenical and social justice concerns. And the great historian John O'Malley gets a shout-out for his book The First Jesuits, which is a must-read for anyone interested in the Catholic Reformation.

This book is an excellent resource for someone wanting to know more about the Jesuits. For some, this concise version will suffice. For others, Collins' bibliographies at the end of each chapter are a priceless gift, making further study easy and accessible.

The whole is well written and Collins assesses and assigns the correct values to events and the personages he surveys. This kind of concise history is like gymnastics: It is a lot harder than it looks. To continue the metaphor, Collins masters every skill and he nails the landing.