A "Stop the Steal" rally is held in Raleigh, North Carolina, on Jan. 6, 2021. (Wikimedia Commons/Anthony Crider)

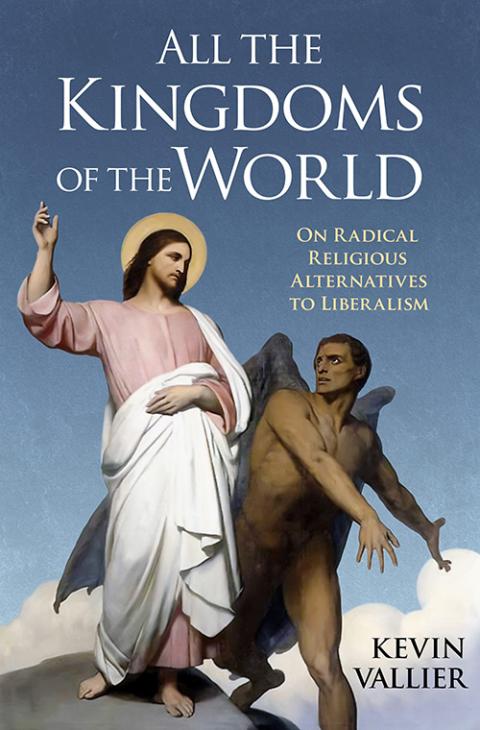

Last week, I began my review of Kevin Vallier's book about Catholic integralism, All the Kingdoms of the World: On Radical Religious Alternatives to Liberalism. Today, I will finish my examination of this fascinating and exasperating book.

The chapter on "Transition" exemplifies this problem with the book, the precise and thoughtful analysis of what is, in the end, insanity. Vallier makes the argument that the transition from a liberal state to an integralist one would require the integralists to violate the very Catholic moral norms they claim to want to embed into the body politic.

He notes that the value of democracy, which has become central to Catholic social doctrine in the post-World-War-II era, is abandoned: "Integration from within attempts state capture," he writes. "The goal? Install integralists in powerful positions in a liberal nation-state. As liberalism falls, integralists seize the state and turn it toward religious objectives."

In addressing Harvard University's Adrian Vermeule's approach to transition specifically, Vallier observes:

As Vermeule so evocatively claims, we must "sear the liberal faith with hot irons." It must not rise again. Only a strong state combined with a strong church can complete this urgent task. Vermeulean protectors must become conquerors. They must rule with an iron rod. And, so, however much Vermeule wants to avoid coercion, he is stuck with it. Integralists must exercise hard power.

Images of the Jan. 6 insurrection flood the mind, only led by the cross and nationwide. It is too horrific to contemplate, and Vallier is right to insist we must not avert our eyes.

In this same chapter, Vallier provides a useful, concise history of the development of the "thesis-hypothesis" theological framing of church-state relations. In an effort to "soften the blow" of Pope Pius IX's condemnation of liberal regimes, the great Bishop Félix Dupanloup of Orleans, France, argued that the pope had articulated the "ideal" situation of the state supporting the Catholic Church as a "thesis," but that the "hypothesis" governed situations where Catholics were in the minority or where, for particular reasons, the ideal could not be realized. In the latter situation, such as in the United States, religious liberty could be embraced.

Vallier goes on to note, "This distinction, designed to save liberalism, later became an obstacle." This is a useful reminder that we ought not abstract issues from the times in which they were debated.

Vallier makes many other intelligent, incisive remarks about a variety of topics in his treatment of "Transition," exposing flaws in the integralist approach.

Advertisement

But every few pages you come across a sentence like this: "The specter of the pope authorizing crusades anew will create global controversy." And you remember that, notwithstanding all the fine distinctions being drawn, the whole topic of integralism is bonkers.

One of the principal contributions of this book is to focus on the integralist ambition to invite the state to enforce the church's canon law. Most critiques of integralism focus on the integralists' desire to have the church's teachings influence the state's conception of the common good.

The idea that the Catholic Church would, at this late date, look kindly on the prospect of civil governments involving themselves in the enforcement of canon law shows why converts like Vermeule really should exhibit more humility about the patrimony they have joined. One lecture with the late, great Msgr. John Tracy Ellis, or any of his famous students, would disabuse them of this idea. The church fought valiantly against secular interference in its internal life, from Henry II to Gallicanism to Nicaragua today. She will guard her hard-won independence fiercely and is right to do so.

The chapter on "Stability" rightly questions integralist assertions that their regime would provide order to society. This chapter is "the book's heart."

Seminarians pray the rosary during a special Mass on Respect Life Sunday at the Cathedral of the Most Blessed Sacrament in Detroit Oct. 2, 2022. (CNS/Detroit Catholic/Valaurian Waller)

Then he adds: "But I fear I may wear down the patience of nonphilosophical readers, so readers should feel free to skip the section that develops my formal model." He is right: This chapter gets bogged down, but it also contains more lethal attacks on the integralist position.

Vallier goes on to explain how integralism works out its understanding of justice, specifically the belief that the state should coerce baptized Christians to follow the dictates of the church, that the government should enforce canon law among the baptized.

The integralists, who are skittish about challenging church teaching, concede that it is wrong to coerce anyone into the Christian faith. Why then is it permitted among the baptized?

Vallier finds that their answer — baptism is a moral transformer — is inadequate, and he is right. And he is right to point out the degree to which integralists, both before Vatican II and today, are shockingly comfortable with double standards, with this difference: Today's integralists end up affording religious freedom only to the unbaptized while the pre-Vatican II theorists claimed it exclusively for Catholics.

A parishioner reaches for holy water upon entering for Mass at Our Lady of Purification Catholic Church in Maina, Guam, May 10, 2019. (AP/David Goldman)

The author then looks at Confucian and Islamic expressions of anti-liberal political ideas. This latter chapter is fascinating and the comparison of these versions of theocratic ideals with Catholic integralism are obvious.

I do not know enough about those cultures to assess his analysis. Nonetheless, there are moments of what all can recognize as keen insight. For example, he examines the competing varieties of wisdom offered by wise sages essential to the Confucian "Way of Humane Authority," noting, "People disagree about which actions manifest virtue, so they will adopt different standards for identifying sages and exemplary persons."

Then he observes, "Worse, sages are rare. Fake, power-hungry thinkers will always have greater numbers and fewer moral scruples." That is brilliantly said and undoubtedly true. Augustine would be proud.

Vallier finishes with a proposal about one way he thinks the integralists could have their kingdom, without violating their principles or creating a radically destabilized regime. He suggests building essentially small, self-contained communities of like-minded integralists, akin to the Amish. (I would point out that the Amish have a rather different ecclesiology from Catholics.) He actually uses the example of the monks of Mount Athos.

The Monastery of Simonos Petra is seen on Mount Athos in Greece. (Wikimedia Commons/Karayan74)

The problem throughout this book, and I suspect most books about integralism suffer from the same problem, is that it is a sane analysis of madness. You make the same kind of marginal notes you do in other books — "strong argument," "good point," and "is this true?" — but then you put it down and wonder if you are still on planet Earth.

Everyone who cares about liberalism needs to pay attention to the integralist critique: For example, the anti-religious stance of some progressives makes authoritarianism more, not less, likely. The integralists are not stupid, but they are unhinged.

The fact that they command a following is frightening and requires everyone to learn more about the movement and why it is so dangerous. This book is not a bad place to start.