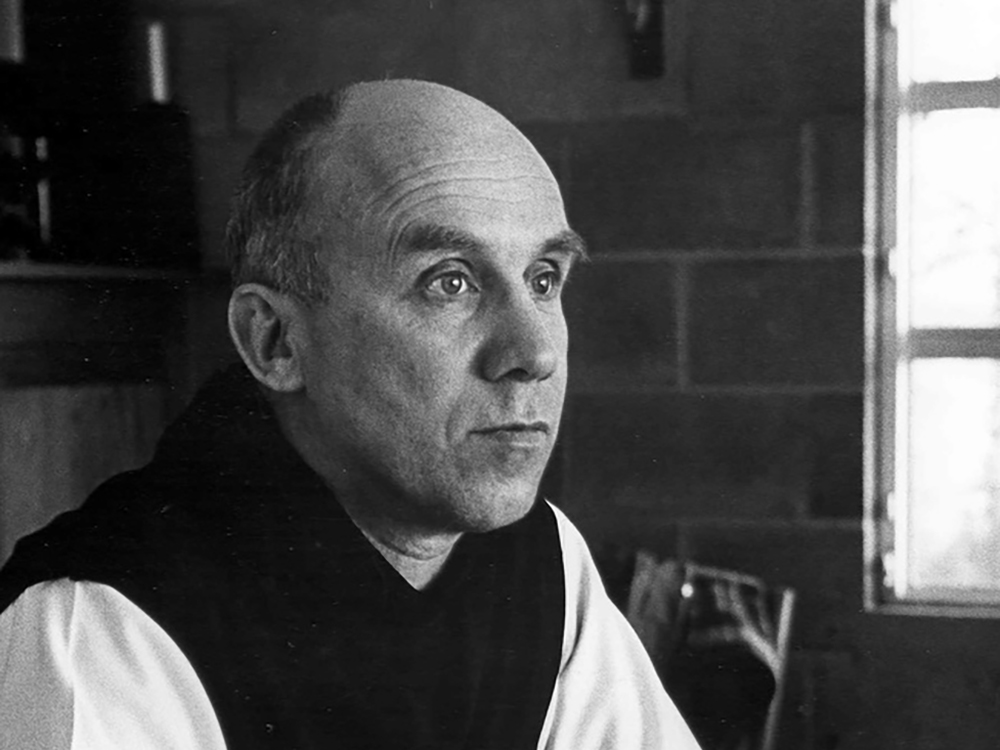

Trappist Fr. Thomas Merton (CNS/Merton Legacy Trust and the Thomas Merton Center at Bellarmine University)

Last month, in the wake of the horrific violence in the Middle East and the ongoing war in Ukraine, I wrote about how the Trappist monk, author and social critic Fr. Thomas Merton's thinking about the relationship between fear and violence continues to speak to our fractured world. But Merton's thinking on nonviolence and peacemaking is not the only place the late mystic and writer's insight continues to be relevant.

As I explain in my recent book, Engaging Thomas Merton: Spirituality, Justice, and Racism (Orbis Books), which was published last week, Merton's wisdom remains timely and prophetic in several ways.

Best known for his writings on the spiritual life and capacious invitation to all Christians to embrace prayer practices and contemplation, Merton also wrote on subjects that spoke to his time and continue to speak to our own. Among the themes Merton engaged in his short life (1915-68), some of the most poignant were those that might seem unexpected coming from a mid-20th-century Roman Catholic priest.

For example, Merton has important things to say about the vocation of marriage, and provides helpful touchstones for couples reflecting on their place in the church and the world.

He provides a nascent framework for a Christian spirituality of marriage, including reflecting on the full legitimacy of marriage as a divine vocation. Merton explains that marriage is not some secondary calling, something less than a vocation to religious life or ministerial priesthood, but is instead a calling from God to live an authentically Christian life.

Advertisement

On the spirituality of marriage, Merton also says that this union of the couple through the sacrament of marriage is a place of divine encounter. Merton writes:

It is by his marriage that he bears witness to Christ's love for the world, and in his marriage that he experiences that love. His marriage is a sacramental center from which grace radiates out into every department of his life, and consequently it is his marriage that will enable his work, his leisure, his sacrifices, and even his distractions to become in some degree contemplative.

Rather than seen as opposed to a life of prayer and contemplation, Merton celebrates marriage as the place where God is recognized and experienced in an important way. He says that the "union of those who are humanly in love with each other is a sacred symbol of the infinite giving and diffusion of goodness which is the inner law of God's own life."

On this same topic, Merton also says that marriage is how spouses become saints. Merton famously wrote in an expansive way about who is capable of participating in God's holiness, long before the Second Vatican Council would explicitly reaffirm the universal call to holiness among the baptized in Lumen Gentium, "The Dogmatic Constitution on the Church."

It is not just the ordained or the vowed religious who are called to holiness, but all people. As he wrote in his 1955 book No Man Is an Island, "How then can we imagine that the cloister is the only place in which men [and women] can become saints?"

In addition to resources for a spirituality of marriage, Merton offers other points for reflection on contemporary Christian life, including insights for ordained ministers and even wisdom that may help today's young adults navigate their spiritual lives in a digital age.

Another way that Merton's writing continues to be extraordinarily relevant is the way in which he reflects on key Christian virtues, which coincidentally resonate with much of the theological and pastoral teaching of Pope Francis over the last decade. Although Merton died a year before Francis would be ordained to the ministerial priesthood, their shared views on themes like mercy, holiness, poverty and love echo across the decades.

While not an academic theologian in the strict sense, Merton did reflect on some deeply theological subjects. One such topic was what we theologians would call the doctrine of revelation, which is primarily related to God's self-disclosure and gift of grace, and secondarily to the inspiration of sacred Scripture.

An interesting insight Merton relates in his writings on revelation is the centrality of divine mercy.

He writes in a posthumously published essay, titled "The Climate of Mercy":

Mercy is, then, not simply something we deduce from a previously apprehended concept of the divine Essence…but an event in which God reveals himself to us in His redemptive love and in the great gift which is the outcome of this event: our mercy to others.

We likewise see timely and inspiring reflections in Merton's writings on the spirituality of holiness, poverty and love. Each of these themes deserves far more space than I have here to unpack. But you can take my word (or read my book) that the way Merton creatively and faithfully engages with these key virtues of Christian life invites all the baptized into a deeper consideration of how we are or are not living after the example of Jesus Christ.

Merton is unapologetic about the fact that systemic racism is a white problem in the United States.

Finally, one of the areas of Merton's written corpus that is both powerfully prescient and disturbingly still relevant is his work on racial justice, especially within the context of the United States.

In Engaging Thomas Merton, I dedicate three chapters to what I call Merton's "spirituality of racial justice." In truth, because there is so much that remains to be adequately studied in this aspect of his thought, I could have used the space of at least three books to unpacking the continued relevance of Merton's prophetic insights on civil rights, systemic racism, white supremacy and the spiritual life.

But as a start, I emphasize that Merton's commitment to what we might call today antiracism is rooted in and consistent with his broader understanding of Christian life and response to violence. For Merton, anti-Black racism is itself a form of violence that Christians — especially white Christians — ought to resist and seek to eradicate.

Second, Merton is unapologetic about the fact that systemic racism is a white problem in the United States. Here Merton joins a chorus of voices, especially those of color, going back to at least W.E.B. Du Bois at the turn of the 20th century, who engaged in sustained truth-telling to the white community about the conditions for the possibility of racial injustice.

The culture of white supremacy in the United States — beginning with settler colonialism and the genocide of Indigenous peoples through chattel slavery and beyond — is the responsibility of those identified as white. Therefore, it is up to white people to change the system, structures and institutions that unwittingly benefit them while concurrently subjugating others.

The way Merton skillfully and insightfully diagnoses the "signs of the times" disturbed many of his fellow whites, especially those intellectual and ministerial leaders in the American North who took his criticism about the way certain whites were inserting themselves into the Civil Rights movement as an unfair attack from a man living in a monastery in the woods.

However, over time, many of those white critics came to see the prophetic truth in Merton's earlier reflections, admonitions and critiques.

One such famous instance of this was in the public exchange between the renowned Protestant scholar of religion Martin Marty of the University of Chicago and Merton. Marty reviewed Merton's Seeds of Destruction in a 1965 issue of The New York Herald Tribune, saying that Merton's assessment of the Civil Rights movement and racism as a white problem was alarmist, pessimistic and offensive.

In 1967, in the pages of National Catholic Reporter, Marty published an open letter apologizing to Merton and acknowledging that much of what Merton had seen clearly and prophetically had come to pass.

We live in an age where it is increasingly difficult to find spiritual mentors and wisdom figures. They do exist — Pope Francis is one that comes to mind — but contemporary Christians and other spiritual seekers may also benefit from returning to a modern spiritual master like Thomas Merton.

In addition to his important works on prayer and contemplation, Merton's lesser-known writing on nonviolence, Christian life, contemporary virtues and racial justice may be just what we need today.