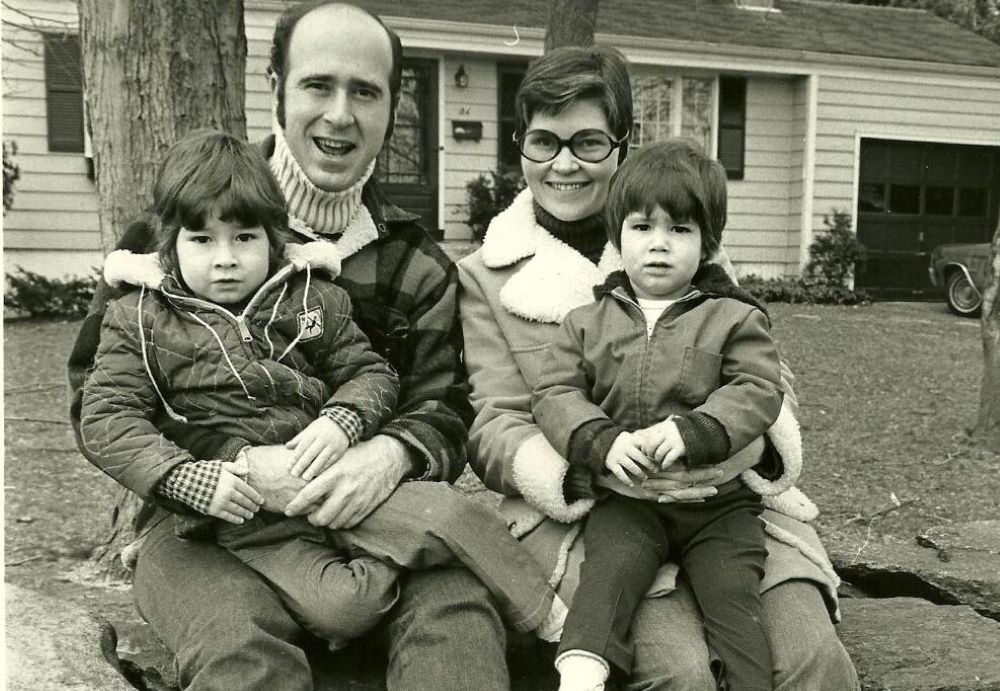

Michael and Vickie Leach pose with their sons, Jeff and Chris, in this circa 1975 photo. Vickie Leach died Oct. 27 after living 20 years with Alzheimer's disease. (Courtesy of Michael Leach)

Vickie was as beautiful in death as she was in life.

My soulmate since first we met at Your Father's Mustache tavern 54 years ago, Vickie died just the way she wanted to. At home. With loved ones at her side.

It happened on Oct. 27 at 8:45 p.m. She was lying in the hospital bed in the living room. The rest of us were eating a late dinner in the alcove by the window. Doctors say hearing is the last thing to go. So, we talked and laughed, believing she would hear the familiar sounds she loved. Vickie's laughter had always been the most robust in the room, but now her mouth was slack and the only sound coming from it was a rasp. Cencia, her caregiver and BFF, got up and went over to check. "Jeff," she said to our younger son who had flown up from his home in Atlanta two weeks ago, "come over."

Jeff put his ear to Vickie's mouth. He heard his mother's last breath.

We all gathered around the bed and cried: Jeff, his brother Chris, Chris' wife Jessica, Cencia, and me. We took turns holding Vickie's hand, touching her arm, kissing her cheek. We hugged each other and cried some more.

I sat by her side for an hour and gazed at her face. Her eyes were open. Jessica tried to close them. "No," I said, "she's fine." I pressed my face to her cooling cheek. "Don't go," I sobbed. "Stay with me, sweetheart. Don't go. I don't want you to go."

Of course, I didn't, and I did. It was time.

Vickie had been living with grace through Alzheimer's for 20 years, her faculties, all of them, eroding faster than the faces on Mt. Rushmore. The past two years she could not walk or talk or scratch her nose without scraping her eye or let us know if she was in pain. Four weeks ago, she was choking on her own saliva. I rushed her to the emergency room. Doctors ran tests all day. That evening they told me and Chris that her lungs were infected, and "it could be this weekend."

Michael Leach sits with his wife, Vickie, in this recent photo. Vickie died Oct. 27 just the way she wanted to: at home with loved ones at her side. (Courtesy of Michael Leach)

We stayed with her in the hospital for five days while her lungs cleared, then brought her home into hospice care. Three years earlier, I had sold our house with too many stairs and bought this one-floor apartment. I remodeled the kitchen and bathrooms and doorways for wheelchair living. I had promised Vickie that I would never put her in a nursing home. If I died first, the boys would hire a live-in caregiver, and their mom would be cared for and live in comfort for the rest of her life.

We put the hospice bed beneath four large movie posters that decorated the long wall facing the television. One of them was my version of "It's a Wonderful Life." Instead of Jimmy Stewart, Donna Reed and their kids, I had substituted our favorite black and white photo of Vickie and me sitting on the rock wall in front of our first house, our toddlers Chris and Jeff on our laps. It was a wonderful life.

We accompanied Vickie for 10 days at home, dabbing the inside of her mouth with a small sponge, giving her small doses of morphine when she had trouble breathing to open her passages and give her relief. If she ate, she would choke to death. If she didn't, she would die of starvation. We told her, over and over, in many ways, that we loved her. I thanked her, over and over, for marrying me.

A compassionate hospice nurse visited twice a day. He told us what doctors had told us. Let her know that it is OK to let go. She needs to know that you will be OK. It was difficult to do. I whispered in her ear: "Mama, is waiting for you, sweetheart. Daddy too. You can relax now. You don't have to struggle any more. I'm going to be OK. I'll always be with you. I'll always be right here."

Vickie Leach worked as a teacher and an assistant principal of a Connecticut high school. Here she wears her favorite red school suit. (Courtesy of Michael Leach)

We used to talk about heaven. Vickie wanted to go to heaven. She knew that it had to be better than this valley of tears we have to wade through first, doing our best to make it a place of springs. Once I asked her what she thought heaven would be like. "It will be wonderful," she said. "It's the beatific vision."

"What's so great about that? You just sit around all day and watch a movie in Cinemascope? That sounds boring."

"No," she said gravely, "it's the Beatific Vision."

When Vickie died her face was a beatific vision. She had no wrinkles. She had some when she was alive. In death she was as pure as the moment God created her.

We had the Mass, a celebration of her life, at Our Lady Star of the Sea, a lovely little church that cuddles Long Island Sound. Vickie had died the way she wanted to, and now she had the Mass the way she wanted it to be. I was at peace. But my heart had a hole in it large enough for a cruise ship to sail through. I had given her permission to go but I wanted her now even more than when she was alive. You never know how much you are going to miss someone until they are gone.

The night after the Mass, we had dinner with some of Vickie's extended family. Two of her nieces from down South, Sarah and Mireille, shared with me stories of experiencing their mother's presence after she had died. I was familiar with true stories of cardinals appearing to loved ones after death. One of my favorite books that I edited back in the day was called Gift of the Red Bird.

Advertisement

That night was my first night alone in more than 50 years. I brought home the big poster of Vickie in her favorite red school suit she was an assistant principal) with its white blouse and black and gold broach. I had made the poster for the Mass and had put it among the flower arrangements at the altar. I now placed it on the big open shelf of our bookcase with an overhead light that made it glow. It had the effect of one of those paintings of Jesus whose eyes keep following you around the room. Unlike those staring eyes, Vickie's eyes twinkled and smiled and embraced me with love. "Stay with me," I said. "Don't leave me." Her presence was in the room as if she had never left.

I barely left the house for three days. I began to wonder if my holding on to Vickie was keeping her from living the full joy of eternity that was her due. I didn't want her to be a ghost in a haunted condo. I wanted her to be free to be everywhere just as much as I wanted her to stay with me.

The next morning, I was on Facebook, and without looking for a sign, the poem "A Little Bird" from Donna Ashworth's book Loss appeared. The bird wants me to know that she is "free as a fledgling/emerged from the nest/flying so high above ground." She has found those she had lost and is resting as loved as can be. The bird is Vickie telling me, yes, she is free and that, of course, she will stay with me, she will come down often and lay her hand on my head, reminding me that I still have a life left to live and it's not time to join her yet, "because love wants you living, you see."

I weep uncontrollably for an hour. Vickie is in heaven. She is with me. I weep tears of sadness and joy at once. Sadness that she is gone. Joy that she gives me permission to live just as I had given her permission to die. I go from room to room and her sweet eyes follow me, reminding me that everything on earth as in heaven is perfectly alright.

I talk to Vickie for the next few days. I look at her picture and we smile at each other. More messages appear on my computer: "My face is the first thing you will see in heaven." A Christmas ornament of a cardinal with the words, "I am always with you."

I sit on the recliner at night, reach my hand over to hold hers, just like always. The hand isn't there, but the sense of her presence is strong.

On the fifth day it grows fainter.

On the seventh, I am aware.

On the 10th I do what Vickie asks of me: I go on living.