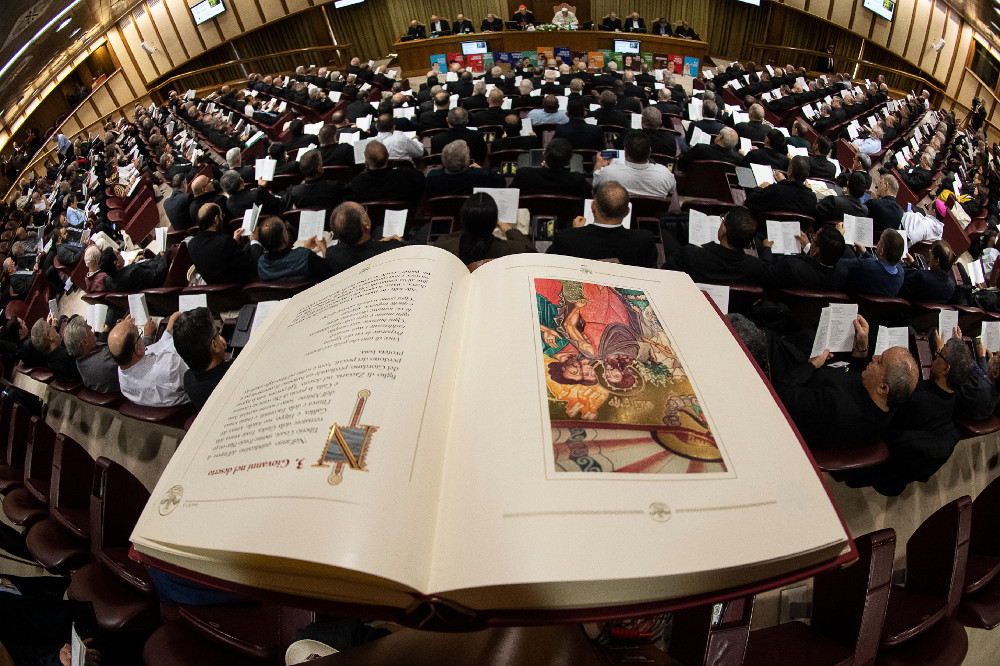

Pope Francis and participants pray at the start of the afternoon session of the Synod of Bishops for the Amazon at the Vatican Oct. 8. (CNS/Paul Haring)

The Synod of Bishops for the Amazon region, being held at the Vatican from Oct. 6-27, got underway well before its official opening with one of the most exhaustive, inclusive and transparent preparation periods yet conducted in the 50-year history of Catholic synods.

Organizers from the Vatican synod office and the Amazon region worked for 18 months, consulting with hundreds of communities across nine South American nations as they hosted nearly 300 local, national and regional assemblies.

The results of those consultations — including the controversial recommendation to allow for married priests on a regional basis — were eventually condensed and made public in the form of the synod's initial working document, known as the instrumentum laboris.

But once the synod's opening business finished the morning of Oct. 7, that practice of transparency effectively ceased. There have been no livestreams of the bishops' discussions, no official release of their texts, and, as yet, no publishing of the work of the synod's small working groups.

Instead, the Vatican press office has been producing rather dry and brief summaries of the major issues discussed in the synod hall each day, and hosting daily briefings where members of the press can try to gently glean more information from two or three synod participants made available.

Vatican officials say the secrecy of the synod process is necessary to ensure that the 184 bishops and priests and one religious brother attending as voting members can speak freely, and undergo a true discernment about the needs of the church in the Amazon today.

"What Francis has done with each recent successive synod … is to make it clear that there need to be more voices, more experiences, more diversity — to help the bishops in attendance listen, discern, and make recommendations."

— Sr. Janice Farnham

Several theologians and long observers of the Synod of Bishops, created by Pope Paul VI in 1965 as the Second Vatican Council was ending, evoked a tension between the desire for transparency in the synod process and the need for church leaders to have time to truly discern.

Jesuit Fr. Thomas Reese, who has reported on a majority of the synod gatherings held since 1985, said simply: "There's a lot less being released now than in the past."

"We get these summaries, and we have no idea who's speaking or how representative they are," said Reese, a former NCR analyst who now writes for Religion News Service.

He pointed to the example of the Oct. 14 summary, which said that one person in the synod hall had spoken in favor of the church maintaining its current practice of mandatory celibacy for priests over allowing for married priests on a regional basis, which is often referred to by the Latin term viri probati.

"We don't know who that it is," said Reese. "We don't know how representative that is, how many people are saying that, as opposed to how many people are talking in favor of viri probati."

Sr. Janice Farnham, a retired professor of church history at Boston College's School of Theology and Ministry, noted that Pope Francis has often mentioned that the synod is not a deliberative body. It is a consultative community engaged in a process of discernment, she said, and the bishops make recommendations to the pontiff for his consideration and possible decision-making.

"What Francis has done with each recent successive synod … is to make it clear that there need to be more voices, more experiences, more diversity — to help the bishops in attendance listen, discern, and make recommendations," said Farnham, a member of the Religious of Jesus and Mary.

Pope Francis leads a session of the Synod of Bishops for the Amazon at the Vatican Oct. 8. (CNS/Vatican Media)

The Vatican's decision to not release the texts of the bishops' speeches might not be what journalists prefer, she said, "but at a certain level, it retains the openness and wide berth needed for all opinions/views/feelings to be heard."

Amanda Osheim, a theologian at Loras College in Iowa, made similar arguments. "While the Synod of Bishops must not be cut off from the larger church, any group engaged in shared discernment needs to develop trust among its members," she said.

The Amazon synod is the fourth called by Francis, who also hosted synods in 2014, 2015 and 2018. The Vatican's practice of officially releasing the bishops' synod texts stopped at the 2014 synod, although the prelates can decide to distribute documents on their own if they wish.

In his Oct. 7 speech opening the Amazon synod, however, Francis warned the bishops that the gathering could "come to ruin" if participants gave too much information to the press. The pontiff said that leaks of information could lead to different gatherings being held outside and inside the official synod hall.

The inside synod, said the pope, "follows the path of Mother church," while the outside synod involves "information given with flippancy, given with impudence, that leads journalists to make mistakes."

One reason theologians pointed to for the Vatican not distributing the bishops' texts is that under Francis' leadership the prelates are being encouraged to speak more openly.

Where under past papacies the synod was known as a talking shop with little actual debate — John Paul II was said to read his breviary to pass the time — Francis has told the bishops to speak with parrhesia, using a Greek term that means to speak boldly without fear.

Advertisement

Massimo Faggioli, a theologian at Villanova University, noted that recent synods have involved something of a new development: outside groups hosting events in Rome before or during the gathering to try and influence the bishops' discussions.

An Oct. 5 event hosted by conservative groups, for example, included apocalyptic warnings that the synod would result in the "dismantling" of the entire global church.

"It is visible now the development of what we could call a 'peri-synodal space' — a space just outside the synod … where all the voices, influences, presences have an effect on the synod, much more than before," said Faggioli, who has focused his research on the church in the decades since the Second Vatican Council.

"This happens because the synod is no longer scripted, but it wants to be a real space and moment for discerning and making decisions," he said.

"Total transparency is something when the synod is scripted, but it is something else when there is no script," Faggioli said. "In other words, it is a way to defend the synod from the danger that other 'scripts' will intervene and limit the freedom of the synod."

Reese, a political scientist who wrote his first book on American tax policy, compared the issue of the synod's transparency to similar discussions about the workings of the U.S. Congress. He mentioned that tax writing committees used to meet behind closed doors.

"Sometimes people could vote against their districts, because nobody knew how they voted, and they might actually vote for the common good," said Reese. "Whereas, once they were public, they would be crucified by special interests if they voted the wrong way."

"When you're involving the church, I think there should be an opportunity for the bishops to have free exchanges so that they can argue and change their minds," he said. "On the other hand, what they're doing impacts the whole church. And so, the whole people of God should be involved."

[Joshua J. McElwee is NCR Vatican correspondent. His email address is jmcelwee@ncronline.org. Follow him on Twitter: @joshjmac.]