A prayer service inside St. Peter's Basilica starts the first session of the Synod of Bishops for the Amazon at the Vatican Oct. 7, 2019. (CNS/Vatican Media)

Five years ago, on Oct. 7, 2019, St. Peter's Basilica in the Vatican rang with voices singing of the Amazon.

Men and women, some in traditional Indigenous dress, filled the transepts and dome of one of Catholicism's holiest sites with a song of prayer alongside cardinals and bishops. In front of the towering main altar, they lifted a small dugout canoe bedecked with fishing nets and surrounded Pope Francis, accompanying him in a procession to the neighboring audience hall where the pontiff opened the monthlong deliberations of the Synod of Bishops for the Pan-Amazon region.

That image remains vivid for Immaculate Conception Sr. Joaninha Madeira, a member of an itinerant missionary team that ministers in communities along Amazonian rivers.

"It was like saying, 'Look, something new is beginning in the church.' We have to keep going in that way, walking with the people in synodality," she says.

The procession was only one of the various ways the Amazon synod broke new ground and charted a path for the Catholic Church that continues to reverberate, both in the South American biome and beyond. As the second and final session of the synod on synodality continues at the Vatican, the roots of that meeting trace back to its precursor a half-decade earlier.

Pope Francis walks in a procession at the start of the Synod of Bishops for the Amazon at the Vatican Oct. 7, 2019. (CNS/Paul Haring)

It was the Amazon synod that first preceded its assembly in Rome with a series of "listening" sessions in which tens of thousands of people from the eight Amazonian countries — Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, Guyana, Peru, Suriname and Venezuela — and the territory of French Guiana participated. The monthlong Amazon synod also saw men and women — lay, clerical and religious — speak in the sessions, although ultimately only bishops voted on the final document.

In the time since the Amazon synod, its echoes likewise are felt across the vast region. While some observers say the church has moved too slowly to implement its recommendations, others say the deliberate pace is necessary to ensure that changes made will not easily be undone.

Dreams for an Amazonian church

In opening the synod for the Amazon, Francis said he sought to give the church an "Amazonian face." And in Querida Amazonia, the papal exhortation issued after the synod, he spoke of having four dreams — social, cultural, ecological and ecclesial — for the Amazon.

"The dreams are the horizon of the reign of God," says Cardinal Pedro Barreto Jimeno of Peru, a Jesuit who is close to Francis, and who now heads the Ecclesial Conference of the Amazon (CEAMA, for its Spanish initials), a new church structure that grew out of the 2019 synod.

The synod itself grew out of Francis' own awakening to the importance of the Amazon basin for the world, and the particular challenges for the church in the region. As Cardinal Jorge Bergoglio of Buenos Aires, he headed the commission at the 2007 Latin American bishops' assembly in Aparecida, Brazil, that wrote the first official Latin America church document to include a section about the Amazon.

At the Amazon synod, Indigenous participants described threats to their lands from illegal loggers and land speculators who harassed and sometimes murdered people who opposed them, as they had killed Notre Dame Sr. Dorothy Stang in 2005. Church workers spoke of the difficulty of ministering in a place where distances are so great and clergy so few that communities in remote regions have little or no opportunity to celebrate the Eucharist with a priest. That led some synod participants to call for broadening the role of women in church ministry, through women deacons, and also ordaining men with families.

The coffin of slain U.S. missionary Sr. Dorothy Stang is carried by members of the Landless Movement during a funeral service Feb. 15, 2005, in Anapu, Brazil. Stang, a member of the Sisters of Notre Dame de Namur, is one of several martyrs who died to protect the Amazon. (CNS/Agencia O Globo/Ailton de Freitas)

In Querida Amazonia, Francis responded to the Amazon synod's final document, expressing four dreams for the church in Amazonia:

- "of an Amazon region that fights for the rights of the poor, the original peoples and the least of our brothers and sisters, where their voices can be heard and their dignity advanced."

- of a region "that can preserve its distinctive cultural riches."

- of an Amazonia "that can jealously preserve its overwhelming natural beauty and the superabundant life teeming in its rivers and forests."

- of a church with an Amazonian face, consisting of "Christian communities capable of generous commitment."

An aerial view shows trees as the sun rises at the Amazon rainforest in Manaus in Brazil's Amazonas state Oct. 26, 2022. (OSV News/Reuters/Bruno Kelly)

Five years after the synod, those dreams are taking shape, although much remains to be done, Barreto says.

"I believe we're gaining greater awareness in society that we're all brothers and sisters," the cardinal told EarthBeat, though Indigenous people continue to suffer discrimination and attempts to strip them of their land or the resources in their territories.

The Brazilian bishops' Indigenous Missionary Council (CIMI, for its Portuguese initials) reports high rates of assassination, suicide and child mortality among Indigenous groups, as well as slow progress on official recognition of Indigenous territories, a problem that also occurs in other countries, including Peru.

"We've become aware that we definitely have to learn to listen," Barreto says. "That is key for synodality, for walking together with the differences we may have, listening to the diversity of cultures and cosmovisions, and learning to dialogue for the common good."

The ecological dream worries him the most.

Called the "lungs of the planet," the Amazon basin is suffering a severe drought this year, with water levels in some rivers at the lowest levels ever recorded. Amid the drought, high temperatures and strong winds have fanned a brutal wildfire season, with the dry conditions fueled more by common practices of burning fields to increase their fertility, or burning trees and brush from forests razed mainly for cattle ranching.

Smoke billows from a fire in August 2020 in an area of the Amazon jungle as it is cleared by loggers and farmers near Humaita, Brazil. (CNS/Reuters/Ueslei Marcelino)

Scientists warn deforestation and climate change have pushed the Amazon closer to a "tipping point" — one where a cascade of uncontrollable events causes the once lush tropical forest to become grassland — than perhaps climate models have suggested. Such a change would have dire impacts for the region's enormous diversity of living things, as well as for the entire planet, which depends on the huge pulse of freshwater from the Amazon River and the forest's role in regulating the global climate.

"That dream is going to take many years. Decades. Perhaps — though I hope not — centuries, not only to care for nature, but to restore nature, because the damage has already been done," Barreto says.

New church structures forming

Barreto is more optimistic about the ecclesial dream, which has taken shape with the continued work of the Pan-Amazonian Ecclesial Network (REPAM, for its Spanish initials) and the creation of CEAMA. REPAM is generally viewed as a platform for interconnecting church jurisdictions throughout the eight Amazonian countries, while CEAMA is a different kind of church structure.

CEAMA's boundaries are not determined by national borders, but by the biogeography of the Amazon basin. Its makeup is more diverse than that of most bishops' conferences. Although the president is a bishop or cardinal, the two current vice presidents are Indigenous women, one of whom is a religious sister. The leadership group also includes a lay man, another religious sister and an Afro-descendant priest.

Advertisement

Each of the seven bishops' conferences that include part of the Amazon basin (Guyana, Suriname and French Guiana belong to the Antilles conference in the Caribbean) is represented in CEAMA with a bishop, a priest, a lay person and an Indigenous representative. As a result, when the full assembly meets, there is a diverse group of about 50 people from around the region, Barreto says.

CEAMA's organization marks another step in the direction of modeling the Amazon synod's intention of modeling a different way of being church. And although some critics have argued that it creates another layer of hierarchy, the new model is winning over some skeptics.

"When it started, I thought it was another name for the same structures," says Florêncio Vaz Filho, a Franciscan brother and anthropologist in Santarem, Brazil. "But I believe it is a tiny door, a small opening, where the church, in an ecclesial sense rather than an episcopal sense, can move ahead."

"That is key for synodality, for walking together with the differences we may have, listening to the diversity of cultures and cosmovisions, and learning to dialogue for the common good."

— Cardinal Pedro Barreto Jimeno

The synod's long reach

The Amazonian synod's influence is already being felt in other parts of the church.

In 2021, the Conference of Bishops of Latin America and the Caribbean (CELAM) held an ecclesial assembly rather than a conference of bishops, with a broad-based consultation in advance and participation by lay people and religious in the plenary. That Latin America-wide process was modeled on the consultations held as part of the Amazonian synod, and was scaled up to the global level for the synod on synodality.

"This isn't a Catholic Church that comes from far away to evangelize, with its light and its shadows," Barreto says. "Now it is the church of Amazonia, after four centuries, which wants not only to continue evangelization in Amazonia, but also to be a contribution to the universal church."

The Amazonian synod also sought to highlight the basin as fertile ground for putting into practice the principle of integral ecology laid out in Francis' 2015 encyclical "Laudato Si', on Care for Our Common Home." The final document noted the impact of extractive industries, such as oil production, which foul rivers and forests with spills, and mining, which is increasing in some countries as demand increases for minerals associated with the clean energy transition.

In addition, the final document denounced human rights violations related to such industries, supported campaigns for divestment from companies that cause environmental damage or harm local communities, and endorsed "a radical energy transition" to alternative sources less harmful to the Amazon — stances reflecting the work of the ecumenical Churches and Mining Network.

A view shows a deforested area in the middle of the Amazon rainforest near the Transamazonica highway in the municipality of Uruara, Brazil, July 14, 2021. (OSV News/Reuters/Bruno Kelly)

On at least one issue, however, the synod for the Amazon failed to move the needle.

The proposal to open the diaconate to women, which was widely discussed in the synod, was omitted from Querida Amazonia. And although it emerged again in the first session of the synod on synodality, it is not on the agenda for the second.

Nevertheless, other steps besides the diaconate can be taken to expand options for women, says German Medical Mission Sr. Birgit Weiler, an eco-theologian who served as an expert at the Amazonian synod and is a consultant to the general secretary of the synod on synodality.

"Pope Francis has set and continues to set an example by naming women to positions of responsibility in the Vatican," including those previously only held by men, Weiler says. "So while I believe the diaconate is an important issue, it's not the only one."

A further step, she suggested, would be revising canon law to allow men and women to apply for leadership positions based on their qualifications and "not left up the whims of ecclesial officials."

That would ensure "more women will be included in spaces where decisions are prepared and taken," she says.

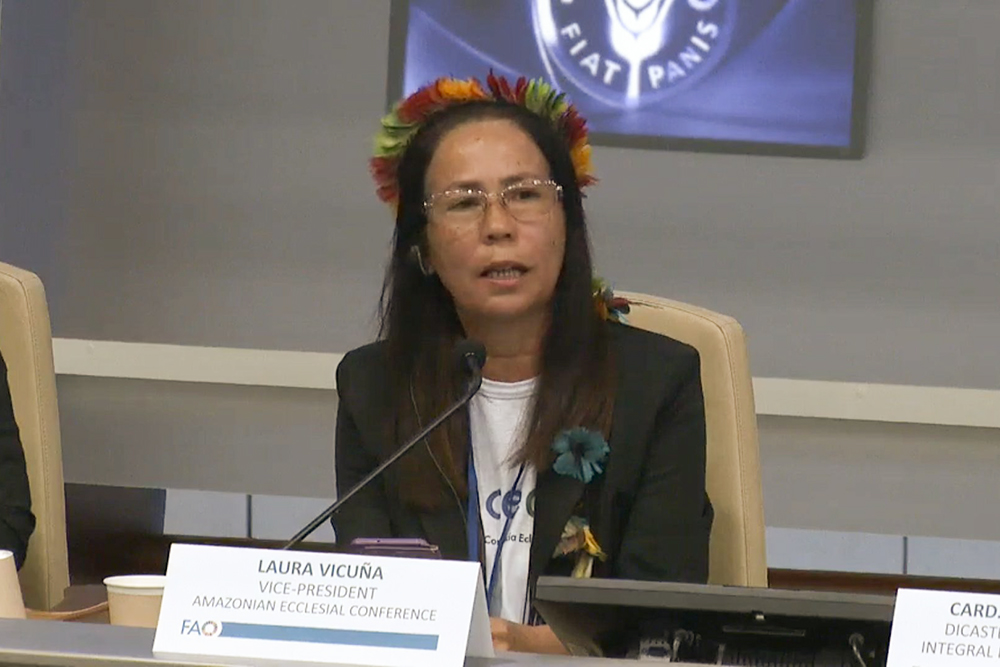

Franciscan Catechist Sr. Laura Vicuña Pereira Manso, who is a member of the Indigenous Kariri people and one of the vice presidents of CEAMA, speaks at an event on the Amazon at the headquarters of the U.N.'s Food and Agriculture Organization in Rome June 4. (CNS screenshot/FAO)

Ministering along the water

CEAMA, which includes a significant number of both religious and lay women, is also moving ahead on other fronts.

A working group developing a proposal for an Amazonian liturgical rite expects to have a draft ready for consultation by mid-2025.

The aim is "to consolidate in the region an autochthonous church, with an Amazonian face, incarnated in its cultures and peoples," Fr. Agenor Brighenti, the Brazilian theologian who coordinates CELAM's theological team, told EarthBeat via email from Rome, where he is participating in the synod on synodality.

Deacon Shainkiam Yampik Wananch prays in a chapel in Wijint, a village in the Peruvian Amazon, Aug. 20, 2019. (CNS photo/Maria Cervantes, Reuters)

Far more than simply adapting the liturgy to reflect Amazonian customs, the Amazonian rite would join the Roman, Ambrosian and Mozárabe rites in the Latin church, in a way analogous to the rites of the Eastern Orthodox Church, Brighenti says. Francis has suggested a model could be the Zairean rite used by dioceses in the Democratic Republic of Congo. The proposal will address various aspects, including the sacraments, initiation into Christian life, ministries, the Liturgy of the Hours, the liturgical space and liturgical year and church structures.

For Vaz Filho, who is a member of the Maytapu Indigenous people of Brazil's Tapajós River and was part of an advisory group of anthropologists working with Brighenti, the rite will recognize the richness of the cultures that were present in the Amazon basin when European missionaries arrived.

"It is a tiny door, a small opening, where the church, in an ecclesial sense rather than an episcopal sense, can move ahead."

— Franciscan Br. Florêncio Vaz Filho

In a background document on the Amazonian rite, the anthropologists proposed "a liturgical year with the rhythm of nature, with the time of creation, the stations and all their biodiversity." They also proposed rethinking the parish structure, especially in urban areas.

Although the popular image of the Amazon is of Indigenous people in traditional dress living in rural communities surrounded by forest, most of the region's population is now urban, and cities continue to grow. The background document suggests decentralizing parishes into networks of faith communities. A new vision of urban ministry must include ways of reaching young people and respond to the faster pace of urban life, Vaz Filho adds.

Migration from far-flung communities to cities poses new challenges for rural ministry, as well.

A woman waves while paddling a canoe in Santarem, a city in Brazil's northern Para state, April 11, 2019. At the time, one river in the Archdiocese of Santarem has 54 Catholic communities along its banks and only one priest to serve all these communities. (CNS photo/Paul Jeffrey)

Even before the Amazonian synod, a mixed group of missionaries — lay people, women religious, priests — formed itinerant, or traveling, teams to minister to communities along Amazonian rivers.

The teams were among the first to systematically break through the geographic barrier of national boundaries, choosing to work along shared borders, such as the place where Peru, Colombia and Brazil converge along the Amazon River, or where Peru, Brazil and Bolivia join farther south. A team now works on the Rio Negro, along a remote border shared by Colombia, Venezuela and Brazil.

Ministering along rivers — the arteries that connect people and ecosystems in the Amazon — makes sense in the region and reinforces its sense as a place identified by its biome rather than by national boundaries, says Fr. Fernando López, who founded the itinerant team some two decades ago, long before the shortage of missionaries, both priests and religious, became a key topic for discussion at the Amazonian synod.

The mobile teams fill a gap left as missionaries, both men and women, age and are not replaced by younger colleagues. Around 15 religious congregations and societies have assigned members to the itinerant teams and committed to supporting those people.

A leader of the Celia Xakriaba peoples walks along the banks of the Xingu River in Brazil's Xingu Indigenous Park Jan. 15, 2020. (CNS/Reuters/Ricardo Moraes)

After the Amazonian synod, there was an increase in interest in the itinerant teams, which participated actively in public events that took place in Rome during the synod, says Madeira.

Today, the team members travel along the river, using the same passenger boats as the people who live in the communities and sharing in everyday activities in the communities they visit. They see their role as building church by helping to interconnect communities.

Working along Amazonian borders is more hazardous now than it was a decade or more ago. The triple-border areas, especially, are key transit areas for drug runners, human traffickers and illegal miners who operate huge dredges that stir up large amounts of sediment and foul rivers with mercury.

Organized crime groups and corrupt police or politicians often take a bite out of those businesses, making the Amazon particularly dangerous for grassroots leaders who speak out publicly against illegal activities — around logging, mining, hunting and fishing, as well as drug trafficking and land grabbing — in their territories. Colombia and Brazil lead the list of countries with the most murders of people for defending their lands and territories in the past dozen years, according to the international watchdog group Global Witness.

Those problems underscore the obstacles that the church in Amazonia continues to face in its efforts to bring Francis' dreams to fruition.

Nevertheless, Barreto, who turned 80 this year, remains optimistic.

"I'm living with great hope, active hope" that there will come a time when the region's Indigenous peoples are respected, and when people talk about their differences and seek the common good, he says.

His own dream is that Amazonia will be a place "where there can be a harmonious relationship among cultures, where the environment is respected and the church is deeply rooted in the heart of the people. That is the hope that is growing in me. Not because I am going to see it, but for the children and the generations to come."