Author Rod Dreher speaks March 15, 2017, at the National Press Club. (CNS/The Trinity Forum)

In 2003, conservative Catholic writer Rod Dreher took to the pages of The Wall Street Journal to criticize the Vatican, and specifically Pope John Paul II, for opposing President George W. Bush's invasion of Iraq.

Like fellow American Catholics such as Fr. Richard John Neuhaus, Michael Novak and George Weigel, Dreher believed the war to be justified. Despite constant denunciations of the war from Rome, these avatars of conservative Catholicism sided with their president over their pope.

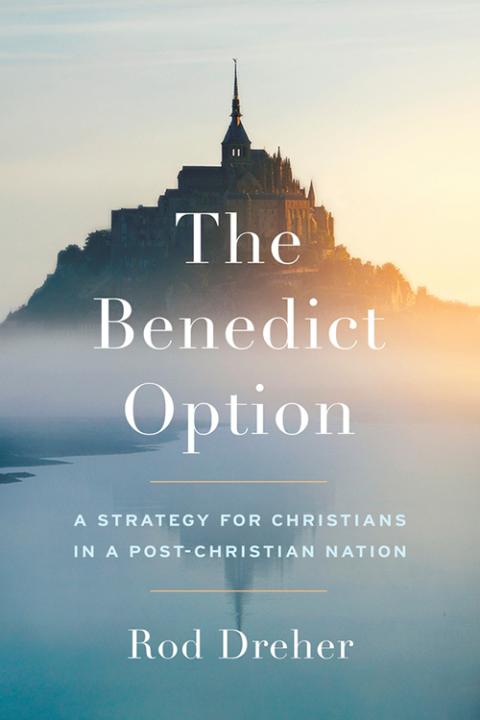

Twenty years later, at age 56, Dreher — one of the most prolific and polarizing figures of the American religious right, whose 2017 bestseller book, The Benedict Option: A Strategy for Christians in a Post-Christian Nation, calls for Christians to "develop creative, communal solutions to help us hold on to our faith and our values in a world growing ever more hostile to them" — is in self-exile from his homeland (more on that later), living here in the capital of Hungary and rethinking much of his early life.

The cover of The Benedict Option: A Strategy for Christians in a Post-Christian Nation by Rod Dreher (CNS)

"The shame I feel over my Iraq War support is probably the most politically significant lesson I've learned in my life," he told me earlier this month, when I met Dreher at a cafe just a stone's throw away from Budapest's impressive neo-Gothic parliament building.

"Watch out for your emotions, your passions can greatly shade your views and you can make very foolish calls," he warned. Still, it would be hard to mistake the Dreher of 2023 as an irenic soul.

I had sought Dreher out because, despite being a notorious critic of Pope Francis — previously characterizing Francis as a "threat" to Catholicism — the pope was in Dreher's newly adopted home of Budapest for an April 28-30 visit.

Prior to the pope's arrival, Dreher had taken to social media to declare the 86-year-old Francis' visit to Hungary, just a few weeks after a hospitalization for bronchitis, as "heroic" while qualifying that his underlying concerns about the pontiff had not changed.

Incidentally, one of the most common beers in the country is the brand named "Dreher" — "It's the Pabst Blue Ribbon of Hungary," he told me. Despite sharing his last name, he's no great fan of it and we both opted for a glass of white wine as he made his case that "the Vatican and Hungary are the only ones who want a peaceful solution" to the war in Ukraine.

Since Russia's February 2022 invasion of Ukraine, Francis has repeatedly condemned the war and pointed the finger at Russia as the aggressor. At various points, however, he has angered Ukraine and its allies by saying the war could not be reduced to a distinction of "good guys and bad guys" and demanding that both countries lay down their weapons.

Despite its membership in the European Union, Hungary, which shares an 85-mile border with Ukraine, has repeatedly distanced itself from Brussels' ironclad support of Ukraine and inched increasingly closer to Moscow and Beijing in recent years.

While Hungary's Prime Minister Viktor Orbán has condemned Russia's invasion, his country's top leaders have continually traveled to Russia to ink energy deals, and as Hungary's economy plummets, Orbán has ramped up his calls for Ukraine to come to the negotiating table.

Yes, it's a case of strange bedfellows, but the ultra-nationalist Orbán, like Dreher, believes that their best ally in this effort might be the more globally minded Pope Francis.

Pope Francis meets with Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán at Sándor Palace April 28 in Budapest, Hungary. (CNS/Vatican Media)

An American patriot loses faith in America

Dreher's move to Budapest in Oct. 2022 was, in many ways, unsurprising.

Orbán's Hungary — which has a strict "no migrants" policy, bans on gay marriage and adoption by gays, and has been heavily criticized for gerrymandering and chipping away at the country's judicial independence — has become a pilgrimage destination of sorts for right-wing superstars, such as former Trump adviser Steve Bannon and, more recently, Florida governor and likely presidential contender Ron DeSantis.

In 2021, Dreher did a stint as a fellow at Budapest's Danube Institute, a conservative think tank that receives funding from the Orbán government. Dreher was also responsible for nudging the recently ousted Fox News host Tucker Carlson to make his high-profile visit to the country in Oct. 2021.

Hungary is a "small country with a lot of lessons for the rest of us," Carlson said during a live-broadcast of his popular cable news show at the time.

Carlson's visit, which Dreher believes helped prove to conservatives that Hungary is not the caricature it has been made out to be, is his "proudest" achievement since being affiliated with the country, he told me.

Despite his own love of travel and his admiration for the Orbán government, Dreher says that his journey here is a path that he wouldn't have chosen, one that was paved by years of tears and pain.

The Danube Institute participates in CPAC Hungary 2022, held in Bálna, Budapest. (Wikimedia Commons/Elekes Andor, CC BY-SA 4.0)

In April 2022, he announced on his blog that his wife of nearly 25 years had filed for divorce. Estranged from much of his family, he packed up and moved from his home state of Louisiana — where he had returned a decade earlier after stints in Dallas, New York and Washington, D.C., writing for outlets like National Review, The Dallas Morning News and The American Conservative — and headed for Hungary.

Today, he's living in an apartment overlooking the Danube that he shares with his oldest son, who is spending the year abroad before returning to America for graduate school. His two younger children, of whom he says he's "not in touch right now, but hoping that might change soon," live back at home in the United States with their mother.

When I meet him on a Saturday afternoon, he complains that he's in need of a haircut, not wanting to risk a foreign barber shop experience, but he appears to be delighted to be enjoying a crisp spring day that offers a marked change from Louisiana humidity. He laughs when I ask him how his Hungarian is ("I started DuoLingo this week!" he replied.).

Over the years, Dreher — who, along with The Benedict Option, has authored titles such as Live Not by Lies: A Manual for Christian Dissidents and Crunchy Cons: The New Conservative Counterculture and Its Return to Roots — has made a name for himself as an apologist for the importance of the traditional family and an emphasis on localism.

But he doesn't mince words about how relieved he is to be away from most of it. Dreher reminds me that he didn't vote for Trump and says he is "sick" of most Christians thinking politics is the key to their salvation when "it never seems to occur to do something on their own." It's time to do something new, something creative, he believes. Like move to Budapest, I ask?

Here in the Hungarian capital, he says he is spending much of his time pondering the question: "What does it mean to be an American patriot when I've lost faith in almost all American institutions?"

Although he once supported the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, he now believes the U.S. military has become too expansive. He is convinced the American government repeatedly lied to keep the country involved in those fights.

In hindsight, he admits, "1989 me — the me graduating from college — would be shocked by the peacenik that I've become in my middle age."

Rod Dreher, top center, attends "The Post-Liberal Turn and the Future of British Conversatism," a one-day conference held at the Danube Institute in Budapest, Hungary. (Wikimedia Commons/Elekes Andor, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Despite these newfound pacifist tendencies, however, Dreher is still at war.

His primary enemy: the sexual revolution, which he believes the U.S. government, corporate America, academia and the media have not only gone along with, but also are aggressively compelling others to do the same.

During a conversation lasting more than two hours, almost every example of America's decline that Dreher cites is traced back to sex: corporate employees being forced to wear pride flags, American professors being fearful to dissent when it comes to the push for transgender rights and the wokeness of the American military.

And now, he believes it is for export.

"The cultural imperialism of the United States has just pissed me off," he tells me. "I have a chip on my shoulder about it. I really f—ing do."

Subtlety has never been Dreher's strong suit.

Over the years he's acquired a reputation resulting from his impassioned, sometimes seemingly endless and manic blog posts in which he has opined on everything from circumcision to classical music. Even his critics, however, have been deeply moved by his candor and the painstaking honesty of his reflections about his troubled relationship with his father, and most recently, his decision to leave Louisiana.

Dreher cited the political philosopher Hannah Arendt who warned about the widespread loss of faith of institutions in her 1951 book, The Origins of Totalitarianism.

"And that's where we are," he said.

"Big business, academia, media and the state are working from the same script," he continued. "If not for the Orbán government, there's no way to resist Washington and Brussels and woke capitalism."

Demonstrators march around the Hungarian parliament as they protest against Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán and a new law forbidding the promotion of homosexuality or gender change for minors, June 14, 2021, in Budapest. (CNS/Reuters/Marton Monus)

'The Benedict Option' in Budapest

Much of Rod Dreher's adult life has been spent rejecting and then attempting to reconcile with the people and places that formed him.

His "idolization" of Pope John Paul II, he said, led him first to convert to Catholicism in the early 1990s in search of the "father figure I wanted." But he left after the eruption of the clergy sexual abuse scandals and joined the Russian Orthodox Church.

Warm memories of his hometown in Louisiana, with its tight-knit population of 1,700, drew him back there when his sister received a terminal cancer diagnosis in 2010, hoping that he might once more find a sense of community.

In Orbán, Dreher sees the kind of political strongman committed to what he describes as a willingness to say no to encroachments upon Hungary's sovereignty that is antithetical to U.S. democracy.

When Dreher first met the prime minister while speaking at a forum in Hungary in 2019, he recalled Orbán telling conference participants to "think of Budapest as your intellectual home."

At the time, Dreher said he kind of scoffed at the idea. But now, he's a believer.

Advertisement

Something special, he says, is happening in a country that was one of Europe's most battered during the Second World War and whose government believes itself to be practically alone on the continent in trying to usher in a quick peace to the war.

While Hungarians have "no reason to love Russia," Dreher says Hungarian citizens are so haunted by the memory of war that they're willing to overlook the corruption of Fidesz, Orbán's political party, in hopes of not repeating the country's political and economic instability that followed World War II.

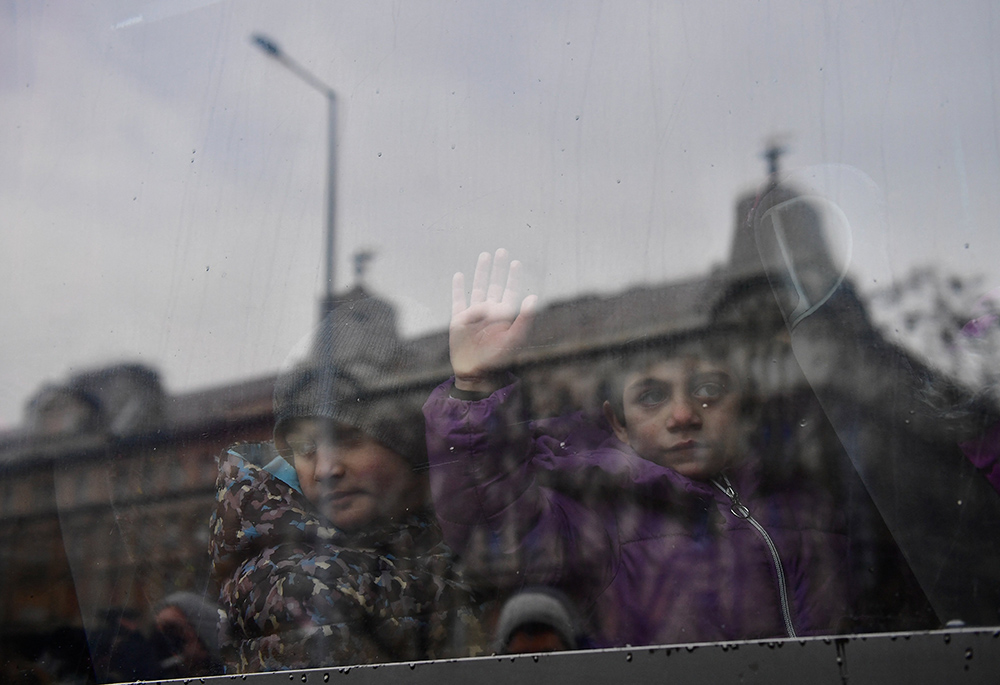

Dreher — who stipulates that Ukraine was "wronged" and that he believes Russia should "get out" of the country — says that while he doesn't know what Orbán's concrete plans for peacemaking would be, he believes a "realistic" solution would be for Ukraine to cede the Donbas region, currently occupied by Russia, in eastern Ukraine, as well as Crimea.

Further, he says he would be comfortable with a "Finlandization of Ukraine," in which the country is officially neutral, with strong guarantees against Russian aggression, but with a commitment that Ukraine no longer seek to join NATO or the European Union.

"The E.U. and U.S. have to formally surrender the idea that Ukraine would be in NATO or EU, just as Russia has to surrender the idea that it has any control over Ukraine," he said.

Children of refugees fleeing from Russia's invasion of Ukraine wait for transport at Nyugati railway station Feb. 28, 2022, in Budapest, Hungary. (CNS/Reuters/Marton Monus)

Such an idea, of course, is anathema to the rest of Europe — including politically conservative Poland, which shares a 330-mile border with Ukraine — which sees Russia as both a physical and existential threat to liberal democracy. It also denies self-determination to Ukraine, which, incidentally, is the case Hungary likes to make about its own sovereignty as a nation.

Orbán believes a bit differently: "Christian democracy is not liberal," he famously said in 2018. "It is illiberal, if you like." In Hungary today, according to Orbán, a little illiberalism is necessary to protect the traditional family, oppose migration and, now, overlook the threats Russia poses to the world order for the sake of peacemaking.

"Saddam [Hussein] was an evil man but the tragedy of politics and geopolitics is that you sometimes have to choose between evils," Dreher said, drawing a parallel between the lessons learned in the aftermath of the Iraq War and today. "I think Ukraine, ideally, should have the right to do whatever it wants, it's a sovereign nation. But unfortunately the world doesn't work that way."

And for that reason, Dreher is temporarily happy to add his voice to those who enthusiastically welcomed Francis as one of the latest noteworthy visitors passing through the country's revolving doors.

"The pope is the only one in Europe who more or less agrees with him [Orbán] on the need for peace," Dreher said.

People who fled Russia's invasion of Ukraine rest at a local resident's home, March 2, 2022, in Tiszabecs, Hungary. (CNS/Reuters/Bernadett Szabo)

Francis and the future of the Catholic Church

En route back to Rome from Budapest, Francis told reporters that he is working on a secret mission to end the war. The mission is secret enough that government officials in Ukraine and Russia have said they didn't know what the pope was talking about, despite insistence from the Vatican's Secretary of State that something is actually afoot.

And for Dreher, he's delighted that the Vatican seems to have found a partner in Hungary to do just that.

"The fact that Francis, who clearly would hate the Orbán government's position on migration, the fact that he cares enough about [ending] war," he told me in the middle of the pope's visit, "even a Francis opponent like me has to doff our cap and say, 'Thank you, Holy Father.' "

But don't expect Dreher to convert to full-time Francis fandom anytime soon.

In fact, while it may be the pope's call for peace that has forced Dreher to give Francis plaudits, he really believes Francis should be at war.

"The church, I think, should be a bastion of resistance," said Dreher. And on this front, he believes Francis has been "on the whole bad for the Catholic Church."

Society no longer accepts a Christian anthropology of the human person, Dreher laments, and he believes Francis is causing further confusion. I asked him if he was immediately skeptical of Francis from the beginning of his election in March 2013, given that he was a Jesuit and from the Global South.

Dreher denies this, but instead points to another moment — again going back to sex — when, in July 2013, Francis made his infamous "Who am I to judge?" reply when asked by a reporter about gay priests.

"I have been frustrated deeply by the way he's muddied the waters of Catholic truth," said Dreher, who noted that he believes Francis' emphasis on synodality — a broad consultation process that includes seeking the opinion of the laity on a number of hot button issues — is "going to destroy, I think, what remaining authority there is in the magisterium."

"When Francis dies, he will have left the church, I think, in a worse place than he found it," he added.

Yet if Dreher is deeply convinced that Francis has been bad for Catholicism, he's equally convinced that Catholicism is necessary for all he holds dear.

"It is the only institution able to stand up to anti-human exploitation, whether it's coming from corporations, our governments or this technological mindset that reduces the human person to a thing to be manipulated," he said. "If the Catholic Church collapses in the West, the West is done."

Three weeks before the death of Australian Cardinal George Pell in January, Dreher had lunch with Pell, where the two Francis critics discussed the future of Catholicism.

According to Dreher, Pell — who had labeled the Francis pontificate a "catastrophe" and was known to be actively planning for the next conclave — was "so in favor" of Budapest's own Cardinal Peter Erdo to become the next pope.

Erdo, Dreher recalled Pell telling him, is "a very fine canon lawyer and this place [Rome] is lawless."

A statue of Ronald Reagan is pictured in the center of Budapest, Hungary. (NCR photo/Christopher White)

"It's going to take a real statesman," said Dreher, to chart a new course for Catholicism.

As we conclude our conversation and leave the cafe, Dreher asks if we can walk a few minutes so he can show me something. Ever the writer, aware of his audience, he jokes: "This will give you great color."

After a short walk we find ourselves at our destination: a bronze statue of Ronald Reagan, erected in 2011 to honor the late U.S. president's efforts to end the Cold War.

Standing there, I asked Dreher about how he makes sense of where he's found himself: a defender of the family who is alienated from his own, an advocate for tight-knit local communities, now living abroad, always seemingly searching to answer the question, "Where is home?"

"I've lost everything," he tells me. "And yet this has been a severe mercy by God. In some ways, this has been the worst year of my life, but I've never felt closer to God." And for that reason alone, he says, he is content with his present circumstances despite not knowing what the future holds.

With that, it was time to part ways. I headed across town to cover another papal event, where Pope Francis would meet with some 12,000 Hungarian young people and cast a very different vision than that of Dreher or Orbán for the future of both their church and country.

And there stood Dreher — alone in Budapest, but in the shadow of Reagan, Pope John Paul II's collaborator in fighting communism, and all of the other ghosts of his past.