Pope Benedict XVI arrives to celebrate a Mass opening the Year of Faith in St. Peter's Square at the Vatican, Oct. 11, 2012. (CNS/Paul Haring)

Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI, known most recently as the pontiff who renounced the papacy, but who was situated squarely at the centers of power during five decades of epochal change and unprecedented scandal in the global Catholic Church, died on Dec. 31 in the apartment he kept inside a Vatican monastery.

A man whose very name conjured images of a return to the theological repression of the 16th century for many, he first appeared on the church's international stage as Joseph Ratzinger, a young German priest-theologian advocating for progressive reforms at the 1962-65 Second Vatican Council.

He was a bishop and cardinal who exalted the position of Catholic clergy, considering them privileged and apart from lay faithful. But he would eventually, following decades of delay, act against sexually abusive priests, after spending hours each week reading through the briefs of the global scandal when he was head of the Vatican's doctrinal office.

For seven years and 10 months, he led the church as the 264th successor of St. Peter, writing documents noted for their spiritual depth and attempting reform of the Vatican bureaucracy.

But he also oversaw a period of general malaise in the church. It had been buffeted by stories of scandal that spread across continents and by a general perception that it had disengaged from the modern world, causing some to even wonder if the millennia-old institution might be past its expiration date.

Then he did something no pope had done of his own free will in more than 700 years: resign. In one humble, surprising act, he made way for a predecessor almost immediately seen as more capable of the office and more able to plot a course for Catholicism's future.

In the end, perhaps Benedict did not so much tower over his times as he attempted to steadily shape them, fashioning theological arguments and critiques in hopes they would find root eventually, if not win immediate acclamation.

News of the former pope's death came on the morning of Dec. 31, after Pope Francis, during his Dec. 28 weekly general audience asked for prayers for Benedict, saying he is "very sick."

The ex-pontiff was known to be in frail health for several years. His only visit outside Italy during his post-papacy was to visit his now-deceased brother Georg in Bavaria in June 2020. He looked frail and was in a wheelchair when he greeted Francis at the Mater Ecclesiae monastery after a consistory for the creation of 20 new cardinals in St. Peter's Basilica Aug. 27.

The Vatican said that his time of death on Dec. 31 was 9:34 a.m., Central European Time. Beginning on Jan. 2, 2023, his body will be placed in St. Peter's Basilica for mourners to visit. The funeral will be held on Jan. 5.

Pope Francis greets retired Pope Benedict XVI at the Mater Ecclesiae monastery after a consistory for the creation of 20 new cardinals in St. Peter's Basilica Aug. 27, 2022, at the Vatican. Looking on is Archbishop Georg Gänswein, the retired pope's private secretary. (CNS/Vatican Media)

Benedict, who led the church from 2005 after the dynamic and commanding Pope John Paul II and before the widely endearing Pope Francis, may not ultimately be most remembered for his public persona or for any single decision he made as pope.

Yet, he will surely be recalled for his long, persistent struggle — first as the cardinal who headed the Vatican's Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith for more than two decades, and then as pope — to implement a narrow interpretation of the wide reforms introduced at Vatican II.

Cardinal Donald Wuerl, whom Benedict moved to Washington, D.C., in his first major U.S. bishop appointment in 2006, said the deceased pope highlighted the need for theological cohesion by connecting the council's changes with the church's past traditions.

"He was the pope of continuity," Wuerl, who resigned as archbishop of Washington in 2018, said in an NCR interview. "His great contribution, I think, was advancing the direction called for by the Second Vatican Council but doing so by reconnecting the advances of today with the council and the great tradition of the church."

German Cardinal Walter Kasper, a renowned theologian who headed the Vatican's Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity under Benedict, said the former pope "left a great heritage to the church as a pope-theologian."

"He has deepened the doctrine of the council," Kasper told NCR. "In his writing, in his homilies, he has deepened our faith, our spirituality."

Pope Benedict XVI's personal assistant, Paolo Gabriele, seated in front left, arrives with the pope in St. Peter's Square at the Vatican May 23, 2012. (CNS/Paul Haring)

U.S. theologian Bradford Hinze said Benedict will "be both criticized and hailed as a staunch defender of a classical Roman and European-centered understanding of the Catholic Church, a position associated with the minority of bishops at the council, though not Ratzinger's own position at the time."

"He will also be remembered, along with Pope John Paul II, for implementing a restrictive view of collegiality and synodality, and of the role of the faithful in the church's mission," said Hinze, the Karl Rahner Professor of Theology at Fordham University and a past president of the Catholic Theological Society of America.

"The death of Pope Benedict may symbolize an end of an era of centralization and clericalism, and mark the new beginning of a polycentric global church and with it a richer understanding of its catholicity promised by Vatican II," he said.

John Thavis, a U.S. journalist who spent nearly three decades in Rome covering the Vatican for Catholic News Service, said that Benedict may be remembered most as someone who strained under the weight of the papacy and could not control the Vatican bureaucracy.

"I think the wider world will remember Benedict as a pope who struggled under the burden of Roman Curia mismanagement and corruption, unable to control the power struggles that weakened the Vatican's prestige and his own pontificate," said Thavis, who worked for CNS from 1983 to 2012, the last 16 years of those as Vatican bureau chief.

"Above all, [Benedict] will be remembered as the pope who resigned," he said. "It was the most courageous decision of his papacy. In one act, this most traditional of popes reminded Catholics that the papacy is not a sacred status, but an office that can, and sometimes should, be set aside."

Advertisement

For many, Benedict may remain something of a conundrum.

An enthusiastic theological adviser to a German cardinal at all four sessions of the Second Vatican Council, Benedict would later spend three decades delimiting its reforms. A theologian familiar with the need for academic freedom, he would enforce new bounds of debate and silence academics around the world.

And a pope seen by many as the expression of the centralized, high-office papacy, he would, in a historic first-in-a-millennia act, renounce the chair of St. Peter.

The implications and historic import of that final decision continue to resound.

With Benedict's death, the world will witness in coming days something never before documented: a pope's funeral, held with high pomp amid the backdrop of the Baroque facade of St. Peter's Basilica, celebrated and led by his successor, who is nearly 10 years into his own papacy.

Fighting a 'dictatorship of relativism'

Elected as pope on April 19, 2005, following the April 2 death of John Paul II, who reigned for nearly 27 years, the German Cardinal Ratzinger immediately struck a much different chord than had Polish Cardinal Karol Wojtyla.

Publicly shy and reserved where Wojtyla had been gregarious, outgoing and even commanding, Ratzinger was also 78 at the time of his election and did not bring the sense of energy that John Paul, age 58 upon his own election in 1978, had brought to his.

Pope Benedict XVI meets with donors of the Papal Foundation at the Vatican April 21, 2012. Pictured are Cardinal Donald Wuerl of Washington, left, and Bishop Michael Bransfield of Wheeling-Charleston, West Virginia, right. (CNS/L'Osservatore Romano)

Ratzinger began his papacy with a straightforward, two-pronged goal. Explaining his choice of papal name to journalists in April 2005, he said he wanted to honor Pope Benedict XV, who pleaded with European leaders for peace during the gruesome First World War, and fifth-century St. Benedict of Nursia, whose life "evokes the Christian roots of Europe."

In the footsteps of his 20th-century predecessor, he said, "I place my ministry in the service of reconciliation and harmony between peoples."

He asked the ancient saint, founder of Benedictine monasticism, to "help us all to hold firm to the centrality of Christ in our Christian life."

Yet, the difficulties that would face him in achieving both goals were obvious even before the beginning of his pontificate. Benedict often took a scholarly tone that seemed disengaged, and sometimes presented the situations of the world in stark and unforgiving ways.

He sharply outlined the challenge he saw the church facing in a homily for the Mass Pro Eligendo Romano Pontifice — "for the election of the Roman pontiff" — following John Paul II's death.

"Every day new sects spring up, and what St. Paul says about human deception and the trickery that strives to entice people into error comes true," he said.

Then, using a blunt term that offered insight into his wider mindset, he added: "We are building a dictatorship of relativism that does not recognize anything as definitive and whose ultimate goal consists solely of one's own ego and desires."

One of the pope's former students in Germany referred to Benedict's use of that phrase — "dictatorship of relativism" — as key to understanding how he saw the role of the church after the council.

'We are building a dictatorship of relativism that does not recognize anything as definitive and whose ultimate goal consists solely of one's own ego and desires.'

—Pope Benedict XVI

Pope Benedict XVI greets the crowd as the arrives to make remarks at the end of a Mass for the Knights of Malta in St. Peter's Basilica at the Vatican Feb. 9, 2013. (CNS/Paul Haring)

Francis Schüssler Fiorenza, a U.S. theologian who attended the University of Münster while Ratzinger was a professor there 1963-66, said his former teacher had initially supported the council's call for more decentralization of church structures in the notion of the collegiality of bishops.

"But when he went to Rome, he favored much more the importance of the central leadership," said Fiorenza, who recalled Ratzinger as normally biking to the university from his residence and as "by far the best and most popular lecturer" at the school.

"I think the issue of pluralism or relativism — as he might see it — came more and more to the forefront of his concerns," said Fiorenza, a professor at Harvard Divinity School. "This shift to the issue of relativism or pluralism reinforced his shift to the importance of the central organization of the church."

Benedict's ability to serve peace was also tested early in his papacy, when he delivered a lecture during a visit to Germany that controversially touched on Islam's role in Europe. He quoted and commented on 14th-century remarks by a Byzantine emperor who said that Islam brought "only evil and inhuman" things to the continent.

The pope apologized for the Sept. 12, 2006, speech and made a point of visiting mostly Muslim Turkey just two months later, but street protests were reported at the time there and in India, Pakistan and Palestine.

Pope Benedict XVI greets the crowd after being elected April 19, 2005. (CNS/Nancy Wiechec)

By the end of his papacy, some were even questioning the firmness of the Christian roots of the Vatican itself.

In January 2012, a television series called "The Untouchables" aired in Italy that alleged massive levels of corruption and deceit inside the church's central command, revealing documents that purportedly pointed to blackmailing of closeted homosexual Vatican clergy.

Eventually, the scandal would unfold with a Vatican trial, where Benedict's personal butler, Paolo Gabriele, admitted leaking information to an Italian journalist in hopes of helping the pope root out the troublemakers.

Gabriele was found guilty in October 2012, but Benedict pardoned him that December.

In March 2012, Benedict had appointed three cardinals to put together a report on the leaks and their aftermath. He received the cardinals' report that December, only to surprise the world with the announcement of his resignation the following February.

Speaking in Latin during a meeting with cardinals at the Vatican Feb. 11, 2013, Benedict said he had a "lack of strength of mind and body" due to his advanced age and would abdicate the papal throne as of 8 p.m. in Rome that Feb. 28.

Among those shocked were the cardinals in the meeting with the pope, many of whom could not speak Latin and had not understood the gravity of his announcement.

Destined for church leadership

Born Joseph Aloisius Ratzinger on April 16, 1927 — Holy Saturday that year — Benedict was the second son and third child of Joseph Ratzinger Sr., a police officer, and Maria Peintner. They lived mostly in the small town of Marktl in the southeastern German state of Bavaria near Austria.

Seemingly destined for high church office from a young age, German language accounts speak of Ratzinger meeting Cardinal Michael von Faulhaber, then archbishop of Munich and Freising, during a school event at age 5 and coming home to tell his parents that he wanted to be a cardinal one day.

The future pope would later be ordained a priest by von Faulhaber in 1951 and would be appointed to serve as the archbishop of the same diocese in 1977.

Growing up under Germany's Nazi regime, he enrolled in the Hitler Youth in 1941 when membership was mandatory, and in 1943 was drafted into military service. He later deserted.

After the war in Europe ended, Ratzinger entered the seminary at age 18 in 1945 alongside brother Georg, who most notably served for nearly four decades as the musical director of the famous cathedral choir in Regensburg.

He earned his doctorate with a thesis on fourth-century St. Augustine and later earned a European teaching credential known as a habilitation with a thesis on St. Bonaventure, one of the first successors of 13th-century St. Francis of Assisi in leadership of the saint's burgeoning order.

In the 1960s and '70s, Ratzinger taught at the University of Bonn, the University of Münster, the University of Tubingen and the University of Regensburg before his 1977 appointment as archbishop.

During the Second Vatican Council, he served as a theological consultant, or peritus, to Cardinal Josef Frings of Cologne, Germany.

After Ratzinger led the archdiocese of Munich and Freising for about four years, John Paul II appointed him as head of the Vatican's Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, where the German would serve as a key adviser to the Polish pope until John Paul's death.

Men look at a giant blow-up of a front page of the German Bild newspaper from April 5, 2005, in Berlin Sept. 19, 2005. The paper features a front-page story about the election of German Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger to be Pope Benedict XVI and reads "We Are Pope." (CNS/ Reuters/Thomas Peter)

Once elected pontiff, Benedict focused his academic acumen in writing three encyclicals, considered the highest form of teaching for a pope, and three apostolic exhortations.

The encyclicals — Deus Caritas Est ("God is Love") in 2005, Spe Salvi ("In Hope We Are Saved") in 2007, and Caritas in Veritate ("Charity in Truth") in 2009 — focused mainly on basic Christian virtues, with the last finding Benedict also widely commenting on the church's long history of social teaching.

In fact, many of the points made in that last document would find an echo in Francis' later teachings. Benedict sounded an alarm for "unregulated exploitation" of the environment, and roundly rejected laissez-faire capitalism, calling it "thoroughly destructive."

One U.S. canon lawyer who worked at the Vatican for two decades during Ratzinger's leadership highlighted the link between Benedict's writings and those of his successor.

"There is no doubt that Pope Benedict was a scholar; one who gave up a scholarly retirement to accept the call of the church," said Immaculate Heart of Mary Sr. Sharon Holland, who worked as a staff member at the Vatican's religious congregation from 1988 to 2009. "His documents are not easy reading and, as a result, probably were not widely read."

"But, as Pope Francis quotes him in documents such as Laudato Si', there is greater awareness and welcome of his teachings," said Holland, who later served as the president of the U.S. Leadership Conference of Women Religious from 2014 to 2015.

St. John Paul II and Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger ride in the popemobile during a visit to Germany in 1980. (CNS/KNA)

Cardinal Wuerl expressed similar sentiments. While Francis is "getting people's attention" in talking about social issues, he said, "Benedict was already addressing them."

Benedict likewise drew praise from several quarters for his actions to confront sexual abuse by clergy in the church. In 2001, while head of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, he convinced John Paul II to make his office the church's global control center to investigate accused clergy and draft policies against abuse.

Under his watch as doctrinal prefect and as pope, hundreds of abusive priests were removed from the priesthood.

He is also credited with pursuing the investigation of Mexican Fr. Marcial Maciel Degollado, a serial child abuser and rapist who founded the powerful and well-connected Legionaries of Christ order. As head of the doctrinal congregation, Ratzinger investigated Maciel, and as pope removed him from ministry in 2006.

Benedict put the order itself into a kind of receivership, appointing a papal delegate to examine its constitution and way of functioning.

In July 2010, the Vatican also announced substantial revisions to canon law aimed at fighting sexual abuse. Benedict extended the church's statute of limitations for sexual abuse cases, made it easier to remove priests from the priesthood, and made possession of child pornography a "grave crime" under church law.

Earlier that year, he had also instructed bishops around the world to follow the norms of civil law, not just church law, when reporting crimes against children.

Thavis, the former Catholic News Service correspondent, said Benedict "took important steps in the Vatican's response to clerical sexual abuse."

"On this score, I think history will be kinder to this pope than contemporary critics," he said.

Pope Benedict XVI signs a copy of his encyclical, "Caritas in Veritate" ("Charity in Truth"), at the Vatican July 6, 2009. (CNS/ Catholic Press Photo/L'Osservatore Romano)

The bounds of theological debate

Under Ratzinger's leadership from 1981 to 2005, the Vatican's doctrinal congregation took a decidedly proactive stance in defining church teaching and in criticizing or warning theologians when they took positions seen as too progressive or outside the bounds.

Under the German prefect, the congregation took particular interest in stemming advancement of liberation theology, a field of theological inquiry that examines Christ's concern for liberation of the world's people from both sin and unjust economic or social conditions.

The congregation issued two so-called "instructions" on liberation theology, in 1984 and 1986, condemning certain elements of study, particularly use of methods of Marxist analysis to examine how the global market system treats the world's poorest.

The congregation under Ratzinger also issued a Profession of Faith and Oath of Fidelity in 1988. Required of all diocesan vicars, seminary rectors, pastors and theologians around the world, it committed those taking it to "hold fast to the deposit of faith in its entirety" and shun "any teachings contrary to it."

Many theologians have criticized Ratzinger for his tenure at the doctrinal congregation, saying he played an overly restrictive role in determining the bounds of theological discussion and unfairly prosecuted theologians he found outside those bounds.

Under Ratzinger, questioning of the church's teaching on sexual conduct, birth control, same-sex relationships, women's ordination and episcopal authority was out of bounds.

Fordham's Hinze pointed to Ratzinger's actions on liberation theology, the oath of fidelity and his encouragement of national bishops' conferences to monitor theologians. Many academics saw such measures "as restrictive and damaging to the contribution of theologians to the life of the church," Hinze said.

"The investigations and disciplining of a significant number of theologians during this period merit comparison with the actions undertaken at the height of the theological controversy described as Modernism," said Hinze, referencing Pope Pius X's early-20th-century crusade that saw sweeping condemnations of theologians and introduction of an anti-Modernist oath for bishops, priests, and theologians.

During Ratzinger's tenure, the congregation contacted many global theologians to make inquiries about the legitimacy of their work. While most of those proceedings were undertaken in secrecy, several resulted in Vatican publication of notifications or condemnations against individual theologians.

Some of the most well-known include:

- The 1997 excommunication, later rescinded, of Sri Lankan Oblate Fr. Tissa Balasuriya;

- The 1998 investigation of Australian church historian and Sacred Heart Fr. Paul Collins, leading to his resignation from the priesthood in 2001;

- The 1998 notification against already-deceased Jesuit Fr. Anthony de Mello of India;

- The 2001 notification against Belgian Jesuit Fr. Jacques Dupuis;

- The 2004 notification against U.S. Jesuit Fr. Roger Haight.

U.S. and Asian moral theologians attempting to adapt theology to their cultural contexts appeared most targeted.

From 2001 to 2005, Ratzinger also quietly raised objections to the Jesuit order regarding its U.S. publication America magazine. At the end of his time as head of the doctrinal office, he called for the resignation of America's editor, Jesuit Fr. Thomas Reese, which took place within a month of Ratzinger's election as pope.

Wuerl, who earned a doctorate in theology before becoming a bishop and has served as a member of the doctrinal congregation since 2012, said that while Ratzinger headed the congregation, he "encouraged theological discussion" and "exercised the responsibilities of that office of the doctrine of the faith with great prudence."

"I believe that he was convinced that because he was a theologian … that the church needs to benefit from theological discussion, theological deepening of our understanding of the faith," Wuerl said.

"But he was very conscious that the health of theological debate in the Catholic Church and its progress depends on the ability of the church, through the doctrine of the faith congregation, to make sure that people don't step outside the boundaries of the continuity of the faith," he said.

"You can't have a good football game if there is no one to say you stepped out of the bounds," he said. "You simply can't. There's no way you can play that game, or any game, without a referee. That's why we have them."

Wuerl added, "I thought Cardinal Ratzinger exercised [that role] very judiciously, giving the greatest freedom but at the same time calling for responsible recognition that there are limits to what constitutes continuity."

Christopher Bellitto, who has written extensively on the history of the papacy, said an "unfortunate" part of Benedict's legacy will be "the notion that this was a man who was not comfortable with open discussion of questions that he thought were closed but others considered open."

Bellitto, a professor of history at Kean University in New Jersey, said that all the church's major councils — from Nicea, to Trent, to Vatican II — "were messy and it's out of the mess that you get good theology."

"When you repress elements, when you don't allow a full discussion, what you end up with is strict but bad theology," he said.

"That may have simply been his persona, his personality," Bellitto said of Ratzinger. "There are some people who want things black and white because they can't deal with the gray. That's fine, but it doesn't mean the gray goes away."

Bellitto also mentioned a common saying that it normally takes the global church 50-100 years to fully understand and accept changes made at councils, or to synthesize them with earlier teachings.

"Ratzinger couldn't be the engine for the synthesis, because he was too personally invested … as a father of the council," Bellitto said.

'A papal act of courage and humility'

After announcing his resignation in February 2013, Benedict said he intended to live the rest of his life quietly in prayer, not wanting to cause confusion or step on the toes of whoever his successor would be.

In the first years following that decision, Benedict indeed led a very quiet life, far from the public eye, appearing only from time to time at major Vatican events when invited by Francis.

By the third anniversary of his resignation, however, Benedict was taking on a bit more of an active role in his post-papacy.

First came a March 2016 interview with a Belgian theologian that focused on the question of God's mercy, just as Francis was in the midst of celebrating an Extraordinary Jubilee Year, also focused on mercy.

In November 2016 came a book-length interview with German journalist Peter Seewald, where Benedict defended his own eight-year papacy against criticism.

"I do not see myself as a failure," he said in the book, titled Last Testament: In His Own Words. "For eight years I carried out my work."

'Above all, [Benedict] will be remembered as the pope who resigned.'

—John Thavis

Perhaps Benedict's most striking intervention from retirement came in January 2020, when he was initially listed as the co-author of a book with Cardinal Robert Sarah, the head of the Vatican's Congregation for Divine Worship.

The volume sharply defended clerical celibacy and was issued as Francis was known to be considering a proposal from the October 2019 Synod of Bishops to allow married priests on a limited basis in the Amazon region.

Announcement of the book's publication shocked theologians, who worried that the former pope's intervention on the subject could tie Francis' hands.

But two days after news of the volume's release, Benedict's longtime secretary, Archbishop Georg Gänswein, told news agencies that the ex-pontiff, by then quite frail, had only thought he was preparing an essay for the volume, and did not intend to be listed as a co-author.

Benedict had also waded into sensitive territory in April 2019, when he published an unexpected letter in which he blamed the clergy sexual abuse crisis widely on the sexual revolution and developments in theology following the Second Vatican Council.

The letter, a lengthy text published initially by several right-wing Catholic websites, immediately drew criticism from theologians, who said it did not address structural issues that abetted abuse cover-up, or Benedict's own contested 24-year role as head of the Vatican's powerful doctrinal office.

Theologians and church historians also expressed concerns that Benedict's choice to engage in such public action played into narratives splitting Catholics between two popes, one officially in power, and the other wielding influence as he wrote from a small monastery in the Vatican Gardens.

Richard Gaillardetz, a theologian who focuses on the church's structures of authority, told NCR at the time that the precedent being set by Benedict's latest letter was "troubling."

The former pontiff, said the theologian, was offering "a controversial analysis of a pressing pastoral and theological crisis, and a set of concrete pastoral remedies."

"These are actions only appropriate for one who actually holds a pastoral office," said Gaillardetz, a professor at Boston College and former president of the Catholic Theological Society of America.

Retired Pope Benedict XVI is pictured among cardinals, including Cardinal Timothy Dolan of New York, right, a few minutes before the start a consistory at which Pope Francis created 19 new cardinals in St. Peter's Basilica at the Vatican Feb. 22, 2014. Benedict's unexpected appearance was his first at a public liturgy since his resignation. (CNS/Paul Haring)

After 32 years in the highest offices of the church as head of the doctrinal congregation and as pope, after 54 years as a theologian, and after 62 years as a priest, Benedict left the Vatican via helicopter Feb. 28, 2013, for the nearby papal retreat of Castel Gandolfo.

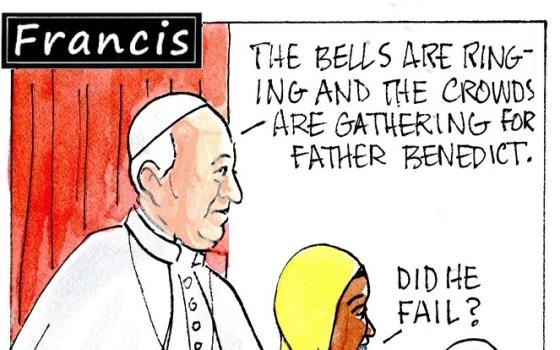

As the helicopter flew over St. Peter's Square, pilgrims and admirers waved goodbye, some seen wiping away tears. As the bells of St. Peter's — the same bells that would announce Francis' election 11 days later — slowly ceased ringing, people in the crowd lingered well past dusk.

At 8 p.m. that night, the doors of the papal apartment were sealed as Benedict's papacy came to an end, as per his own order.

The day before, in his last public audience, the German theologian told crowds that the seven years, 10 months, and nine days of the papacy had been a "great weight" on his shoulders.

"I felt like St. Peter and the apostles in the boat on the Sea of Galilee," said Benedict.

"The Lord has given us many days of sunshine and a light breeze, the days when the fishing is plentiful," he said. "But there were also times when the water was rough … and the Lord seemed to be sleeping."

Holland, the U.S. sister and canonist, said "every pope brings his own gifts to the papacy; each is unique."

"The generosity, intelligence and integrity of Pope Benedict were crowned by his last papal act of courage and humility," she said. "His resignation."

Pope Francis embraces emeritus Pope Benedict XVI at the papal summer residence in Castel Gandolfo, Italy, March 23, 2013. Pope Francis traveled by helicopter from the Vatican to Castel Gandolfo for a private meeting with the retired pontiff. (CNS/Reuters/L'Osservatore Romano)

Yet, in his post-papacy Benedict never publicly criticized or spoke directly against Francis. In fact, in the March 2016 interview the former pontiff praised his successor as responding to the "signs of the times" with his focus on God's mercy.

Chicago Cardinal Blase Cupich, who was appointed to his current post by Francis but had previously served as bishop of Spokane, Washington, on Benedict's appointment, said the former pope's fidelity to his successor was praiseworthy.

"Even in the face of increasing great personal cost and continual suffering, Pope Benedict grew ever taller in his abiding service to the church," Cupich said.

Wuerl spoke of visiting Benedict once after the resignation and said he saw a side of the retired pope rarely seen in public: his humor and his sense of kindness.

The cardinal said Benedict asked him how he was able to write so much despite having such a busy travel and appointments schedule.

Wuerl said he responded that he often finds time to write on plane flights and then asked in return, "Holy Father, are you planning on writing anything now?"

Wuerl recounted the pope — by then almost entirely hidden from the world, living away from the spotlight in a Vatican cloister — joking back: "No, I don't have plane flights."

"It's a side of him that I don't think we experience. … He really had a calming and peaceful manner about him," Wuerl said.

Like many, Wuerl said Benedict may be remembered most for his final act as pope, and then what he did not do afterward.

"He did what he said he was going to do," said Wuerl, remembering greeting Benedict before he departed the Vatican for the last time as leader of the Roman Catholic Church. "He simply stepped off the stage."

"We were going to have a new pope," said the cardinal. "The church only has one pope. And Pope Emeritus Benedict made it very clear — in his actions, his conversations, or lack of public conversations — that Pope Francis is pope and that he, Benedict, is going into retirement and praying."

"That's going to be the historic model and remembrance of this unique moment in modern history, when a pope actually resigned and then went into seclusion," Wuerl said.