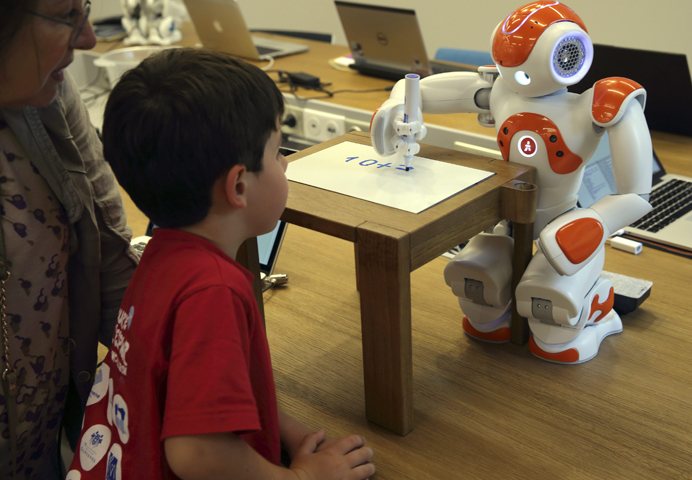

A child watches a humanoid robot, Nao, doing math July 2, 2014, at a Aldebaran Robotics workshop during its opening week in Issy-les-Moulineaux near Paris. (CNS/Reuters/Philippe Wojazer)

NASA is quiet about it, but the fact remains: It is looking for aliens in outer space. What's more, these days, the rest of us almost expect to see them in our own lifetime. They're out there somewhere, we figure. And if they don't find us first, we are certainly going to find them. Maybe under a rock on Mars; maybe in the water beneath the crust of Ceres. Surely somewhere.

If nothing else, the odds alone demand it. Of the 200 billion to 300 billion stars in our own Milky Way and the 100 billion to 200 billion galaxies in the universe, who really believes that we are alone out here?

The problem we're overlooking is that they are already here. Only now, we call them "robots." They, too, are alien to our society but moving in fast. In fact, now we hardly notice them anymore.

I don't think too much about the robots that sweep floors, for instance. I blink but smile at the ones that race up and down hospital corridors, delivering linens and carting off meds. Great programming, I think. But unusual? Not really. I had an uncle whose electric trains carried Christmas candy from one side of the room to the other long after the rest of the Christmas decorations were put away. What were robots, I figured, but a higher level of toy trains?

I changed my mind, though, and rethought the whole issue recently, when I stumbled onto a news clip of doctors who are working on a 3-D print of a replaceable human heart and a video of a man whose "robot" played the violin. Irish jigs and Mozart, in fact. I watched the bow cross the strings while the body of the violin tilted back and forth and the "fingers" played the notes. How long would it take, I wondered, before people would be operating on hearts produced by a 3-D printer and this robot violin would begin to write its own arrangements?

In the meantime, it just kept playing. Over and over. Getting no better, perhaps, but making no mistakes either. Amazing, I thought. Amazing.

But is it? Really?

Oh, as a model of the partnership between computers and human beings, they are blockbusters of an example, yes. But they say so much else, as well, about what it will take now to remain human in a technological world.

As a people, perhaps instinctively, we have been agitated about all this computerization of life for a long time. But we are only now beginning to articulate the concerns these technologies bring us, as well as the services they provide in both the arts and science.

The irony is that we have united the world technologically and, at the same time, made it more difficult than ever for us to unite politically. Unless we really want to, that is; unless we decide to work as hard on understanding as we do on technology.

In a world that speaks over 7,000 languages but that has written forms of only about half of them, how will technology supply for the humanity we need to govern a world such as that? We have a serious communication problem. As the human world and its robots make it more and more difficult to distinguish human operations from robotic ones, what happens to humanity, both ours and the rest of the human race, who can still not write a letter to a missing relative? What happens to human understanding then? Indeed, we need to set out to fathom the soul of the other as we go. Otherwise, no amount of robot-playing violinists or artificial hearts will be able to solve the problems our technology leaves behind.

The more we connect with the rest of the world, it seems, the less we understand how to deal with it. Think of Afghanistan, where our drones are killing civilians. Think of Baltimore, where all our computerized equipment may be able to keep people under control but does nothing to really make them feel more secure, more human, more valued.

There is already a great deal of contact between the Christian and the Muslim world, for instance, but our understanding of Islam lags dangerously behind. Instead, we have come to look at the whole world with a jaundiced eye. Weapons have become our major export, and universal eavesdropping our favorite indoor sport. Then, just in case the intelligence fails, we invent sniper rifles that are deadly accurate three football fields away.

At every level of humanity, we seem to prefer technology to relationships. We don't want diplomacy, and our own Congress undercuts a president who is trying to achieve some. Agribusiness is in the business of turning natural seeds into non-reproducible ones so we can turn food, too, into an international weapon. After all, what can't be reproduced will need to be purchased from us, right? If we're willing to sell it to those people, of course.

And in the midst of it all, irony of ironies, we're writing articles about the dangers of artificial intelligence in robots?

Until we become human enough to foster the humanity in us and around us, we will not be able to handle robots.

Point: The robots aren't the problem. It's the artificial intelligence in ourselves that is the problem.

By now, we have embraced torture, ditched the principle of habeas corpus, ignored the rights of privacy, and opened up specters of Solzhenitsyn's Gulag Archipelago, where everyone is tagged and filmed, followed and listened to till the ancient notion of human rights and the principles of the Enlightenment are only dimming vestiges of a democratic past. Our electronics have ringed the world around with an electronic fence, much the same way we keep our dogs in closed yards that look open.

Indeed, Pogo warned us: We have met the enemy and he is us.

As national elections begin to depend on who wants to buy whom and all wealth rises to the top around the world, we need to stop a minute. We need to ask ourselves who we really want to be and who we have become. And then, as a people, we must demand better.

From where I stand, it seems to me that until then, all the gadgets in our lives may engage us, all the talk of aliens may fascinate us, all our fear of robots may absorb us, but at the end of the day, it will be the alienation of ourselves from our best ideals that will most threaten our way of life and this country.

[Benedictine Sr. Joan Chittister is a frequent NCR contributor.]

Editor's note: We can send you an email alert every time Joan Chittister's column, From Where I Stand, is posted to NCRonline.org. Go to this page and follow directions: Email alert sign-up.