Timothée Chalamet and Zendaya star in a scene from the movie "Dune: Part Two." (OSV News/Warner Bros./Niko Tavernise)

This article contains spoilers for notable 2024 films.

"Beware the vending machine prayer."

This largely unspoken caution shaped my family's spiritual life. The term was coined to reign in my alacrity to view prayer solely as a venue for petition. I grew up knowing that God is able to do "exceedingly and abundantly more than we could ask or imagine" (Ephesians 3:20). I wanted to cash in on God's omnipotence as advertised: Why not pray for a college acceptance, a relative to be cured of disease, for just one more hour to be added to the day so I could turn in an assignment on time?

But prayer was not to be defined or confined solely by asking God to bring things about exactly as implored; but, rather, about alignment of the heart. When we prayed, I was told, the hope was that I'd come to desire the things God desires, that my prayers and God's will would be in lockstep.

If I'm honest, it has been a long time since I have prayed in earnest. But while going to the movies this year, I found myself returning to this idea of prayer as interior calibration to something beyond oneself, not a mere lobbying of requests at the Divine. Even if characters did not explicitly fold their hands and bow their heads (though there was plenty of representation there, thanks to films like "Between the Temples," "Conclave," "Exhibiting Forgiveness," "Heretic," "Longlegs," "Small Things Like These" and "Wildcat," to name a few), many of this year's films featured equivalent desires.

In the new film "Conclave," fictional cardinals (led by Ralph Fiennes, pictured) are tasked with selecting a new pope when the acting Holy Father suddenly dies. (Focus Features)

Some of the notable movies of 2024 interrogated how the things we often "pray" to — whether politics or religious institutions — have not only failed to measure up to their calling, but have actively caused destruction and social upheaval. These films challenge us to be wary of uncritically embracing institutions and to be mindful of what we give ourselves over to, ultimately offering what "prayer" can and should look like while navigating systems of violence and subjugation.

What's striking about this year's movies is how notably congruent they are in theme. Filmmakers often have very little control over when their films are released, and last year's Hollywood strikes affected 2024's output. (Some of the year's biggest titles, such as "Dune: Part Two" and "Challengers," were supposed to be released last year). It's prescient that many of this year's pictures focused on the pitfalls of total devotion, especially of charismatic, manipulative and power-hungry leaders.

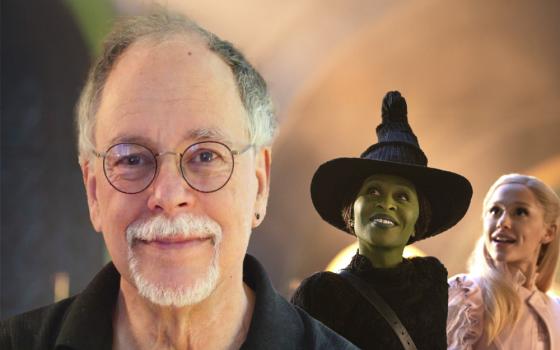

Even before director Jon M. Chu's "Wicked" arrived in theaters, the film's political urgency was palpably felt. The climax of the film revolves around the blossoming witch Elphaba (Cynthia Erivo) realizing that the Wizard (Jeff Goldblum), ruler and benefactor of the land of Oz, possesses no magical power of his own and has been manipulating public opinion to keep himself in power by placing blame on a marginalized group. The parallels write themselves. Many viewers saw their own inner state reflected in Elphaba's disillusionment and rage.

Cynthia Erivo and Ariana Grande star in the movie "Wicked." (OSV News/Universal)

Director Denis Villeneuve's aforementioned "Dune: Part Two" swaps Oz's glitter and glamor for the harsh sands of the planet Arrakis, where the only talking animals you'll find are the giant sandworms that speak in prophecy and ancient, guttural roars. If "Wicked" was about the destabilizing nature of discovering the emperor has no clothes, then Villeneuve's sci-fi epic warns what happens when people see the sins and foibles of those they follow, yet still choose to obey marching orders.

Protagonist Paul Atreides (Timothée Chalamet), an outsider of Arrakis, is believed by many of the planet's native inhabitants, the Fremen, to be the one who can lead their people to paradise and prosperity after years of subjugation by the Harkonnens, who happen to be the Atreidies' sworn enemies. Seizing an opportunity to fuse the Fremen's desire for a messiah and his hatred for the Harkonnens, Paul rallies followers and they destroy the Harkonnen occupancy. The fallout is bittersweet. We end, not with the triumphant battle cries, but with Chani (Zendaya), a Fremen woman who was Paul's friend and then lover, abandoning him and riding away. She has seen the fruit of her people's prayers, how they've been co-opted for evil, and refuses to have a part.

A similar peril manifests in the Oregon-set horror police procedural, "Longlegs." Director Osgood Perkins' film sees FBI agent Lee Harker (Maika Monroe) learn that her mother, Ruth, (Alicia Witt) is an accomplice to the titular serial killer she's been trying to catch. Having been visited by Longlegs when Lee was younger, the killer gave Ruth an ultimatum: aid him in his murder sprees in exchange for Lee being able to grow up and have a normal childhood. Out of love and fear, Ruth agreed; but you can only wipe so much blood off your hands. By the time Lee confronts Ruth with the truth, the mother has been driven mad by her choice and has fully aligned herself with Longlegs' violent crusade.

Maika Monroe stars in a scene from the movie "Longlegs." (OSV News photo/Neon)

Other 2024 films, like Sean Baker's "Anora" and Coralie Fargeat's "The Substance," also feature characters who have found themselves burned by the ideals they trusted in, whether belief in the mobility afforded by late-stage capitalism or unrealistic and oppressive beauty standards.

If this year's movies have redefined "prayer" as a form of participation, then they've also shown how we should be cognizant of what exactly we are "praying" to: whether political systems, religious institutions, desire for comfort and safety or social currency. Such forces make for poor gods indeed.

How, then, are we to pray? Is there a way to fruitfully channel our fury and indignation? If what we trusted to save us only damages us, what are we to give ourselves to? Some of this year's cinema provided a liturgy for prayer in worlds on fire.

Advertisement

In "Conclave," director Edward Berger's mystery thriller about cardinals charged with the task of electing a new pope, Thomas Lawrence (Ralph Fiennes) serves as the dean of the College of Cardinals and his weariness about the election process becomes our own as the proverbial knives come out. As voting begins, Lawrence delivers a nontraditional kind of prayer. "Our faith is a living thing precisely because it walks hand in hand with doubt," Lawrence says to the crowd of scheming men. "Let us pray that God will grant us a pope who doubts. Let him grant us a pope who sins and asks for forgiveness. And carries on."

For those who may have sacrificed and prayed to the gods of power, Lawrence's words remind us that in the embracing of uncertainty and vulnerability, our faith can become alive.

Two other "prayers" from this year point to how prayer still has a place in our world now, even if it may look unconventional or be laced with Lawrence's doubt. Scott Beck and Bryan Woods' "Heretic" centers two Mormon missionaries, Sister Barnes (Sophie Thatcher) and Sister Paxton (Chloe East), who knock at the door of a dangerous man, Mr. Reed (Hugh Grant) in their attempts to share the Gospel. Near the end of the film, we witness an honest and pure form of prayer from Sister Paxton. When chastised by Mr. Reed for praying, she replies, "It's beautiful that people pray for each other, even though we all probably know, deep down, it doesn't make a difference. It's just nice to think about someone other than yourself."

In "Heretic," two Mormon missionaries (Sophie Thatcher, center, and Chloe East, right), are invited into the home of Mr. Reed (Hugh Grant). A guise of desire to learn more about the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints hides Reed's sinister plan. (A24 Press)

For Paxton, by the end of her terrors, it matters less who she prays to and more that she prays at all. Prayer is an act that realigns her heart, not with her desires and emotions, but towards care for others. It even enables her to pray for her enemies.

"Nosferatu" was one of the last films to release this year, debuting in theaters on Christmas Day, and in it director Robert Eggers purposefully revels in all that is unholy. In the very first sequence, we meet Ellen Hutter (Lily-Rose Depp) caught in the throes of prayer. Haunted by something, but not sure what, she quite literally cries out to the darkness: first for deliverance from God, but when the Divine seems silent, gradually expanding her scope to "a guardian angel, a spirit of comfort ... anything." For the rest of "Nosferatu," Ellen — and those around her — will wrestle with the consequences of that open invitation.

The films of 2024 have reminded us that, quite frankly, we all pray — whether or not we fold our hands, even if we may never utter the words "Amen" or have ever directly cried out to God. Ellen Hutter's cries might just serve as a thermometer for our culture's view of prayer: a plea flung from the darkest corners of our souls, not directed at anyone in particular, but one that still longs for an answer.