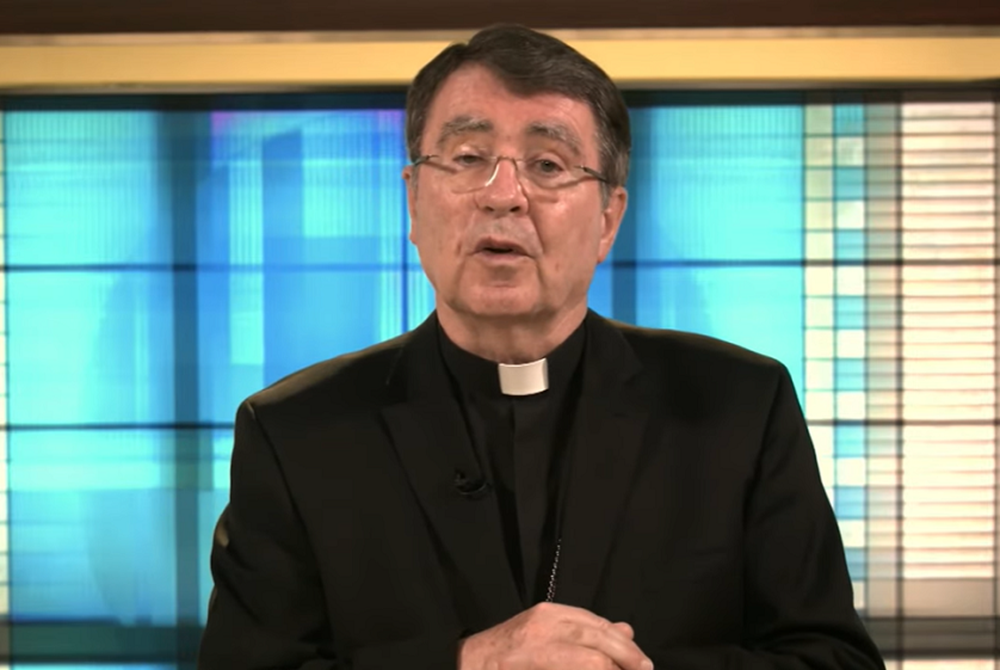

Archbishop Christophe Pierre, apostolic nuncio to the United States, speaks during U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops' fall virtual meeting, held Nov. 16. (NCR screenshot)

The first day of the plenary meeting of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops was disappointing in virtually every regard. Indeed, the only good idea to come from this virtual meeting was the image of some bishops who had neglected to unmute themselves, talking with no sound. It is a metaphor for the conference at this moment in time: Their mouths move but they have nothing to say.

If you wanted to write a short story about the reception of the McCarrick report by the U.S. bishops, you might call it "The nuncio that dare not speak his name." There were a dozen or so interventions in the public discussion of the McCarrick report, no bishop mentioned the name of Archbishop Carlo Maria Viganò, and not one bishop apologized for testifying to Viganò's "integrity" when the disgraced former nuncio used the McCarrick scandal as a vehicle to attack his enemies and call for the pope's resignation.

Asked about this during the press conference that followed the event, Archbishop Timothy Broglio of the Archdiocese for the Military Services said it was not the conference's job to "hand slap" bishops. What Broglio fails to see is that this is precisely the problem at the heart of the McCarrick report: the fact that there was no effective fraternal correction before it was too late. Even when St. Pope John Paul II decided to believe McCarrick's denial that he had done anything wrong, McCarrick's own letter admitted he had shared beds with seminarians. In what moral universe is that OK?

Turns out it is OK in the moral universe of Bishop Thomas Paprocki of Springfield, Illinois. He whined that "unfortunate" media accounts of the McCarrick report painted the late Polish pontiff as culpable in the promotion of McCarrick and cited every bit of mitigating evidence to diminish the pope's responsibility. But the overwhelming fact of the report is that John Paul II made a promotion he did not have to make, he chose the problematic candidate when there were other candidates, and then bestowed the red hat on him. John Paul II cannot evade responsibility for the promotion of Theodore McCarrick through the ranks of the hierarchy.

You can't say that out loud because … why? Let me guess. The people will be scandalized? We have heard that excuse before.

The McCarrick report details a culture that is allergic to candor and uninterested in getting at any truth that might make anyone uncomfortable. That report itself was an exercise in candor and an invitation to the U.S. bishops to continue in that spirit. They declined.

What did we watch at Monday's meeting? Perhaps it was different in the bishops' executive session, but in public session we saw a lack of frankness, feigned politeness, the diplomatic manner of the body, all of those things that served to cover up McCarrick's sins and now keep the bishops from acknowledging John Paul II's sins and the sins of the hierarchic culture itself. Many spoke in the passive voice: "Mistakes were made." Occasionally, someone would say something harsh, provided the target was unnamed. For specifics, we got only niceties.

The current nuncio, Archbishop Christophe Pierre, missed an opportunity to apologize to the bishops and to Catholics throughout the country for the failure of his predecessor to bother to investigate allegations against McCarrick when he had the chance. Pierre's talk was fine so far as it went, but it did not rise to the occasion. I was surprised he did not offer a more forceful defense of Pope Francis and the current pontiff's decision to do what his predecessors refused to do: hold bishops accountable to the same sex abuse standards as priests, punish covering up sex abuse as harshly as the abuse itself, and mount an investigation that lets the chips fall where they may.

Los Angeles Archbishop José Gomez, who was elected president of the conference last year, gave his first presidential address, and it fit the tenor of the meeting. Speaking of the pandemic, Gomez said, "As we know, people's faith in God has been shaken. At the heart of their fears are fundamental questions about divine Providence and the goodness of God."

Gomez failed to denounce the policy of functional euthanasia pursued by the present occupant of the White House. I wish Gomez were my parish priest: He is gentle, kind, thoughtful. But the times require dynamic leadership, and I do not think he has that in him.

The elections for committee chairs showed that moderates are still not able to get elected by this body. The most egregious choice was the election of Bishop Thomas Daly of Spokane, Washington, to lead the Committee on Catholic Education by a margin of 139 votes to 103 votes for Atlanta Archbishop Gregory Hartmayer. I was pleased that Baltimore Archbishop William Lori was chosen to lead the Committee on Pro-Life Activities over Denver Archbishop Samuel Aquila: Lori will be sane and he is smart.

The choice of Broglio to continue as chair of the Committee on Priorities and Plans leaves me dumbfounded. The McCarrick report painted a picture of a highly dysfunctional Vatican curia in the 1990s, which is when Broglio worked at the heart of it. In every contest, the more conservative prelate won.

No one in public session mentioned the U.S. presidential election, nor the fact that we are about to witness the inauguration of only the second Catholic as president. I suspect they consider the fact that President-elect Joe Biden does not toe the line on abortion and some other issues is a rebuke to themselves: If they can't persuade someone as faithful as Biden, what does that say about their powers of persuasion? Given what we know about the politics of some of the brethren, perhaps it is better Biden's name was not mentioned.

There was a time when the U.S. bishops' conference was a model for the rest of the world, an ongoing exercise in effective collegiality that resulted in a forceful public witness to the Gospel. That time has passed.

[Michael Sean Winters covers the nexus of religion and politics for NCR.]

Editor's note: Don't miss out on Michael Sean Winters' latest. Sign up and we'll let you know when he publishes new Distinctly Catholic columns.

Advertisement