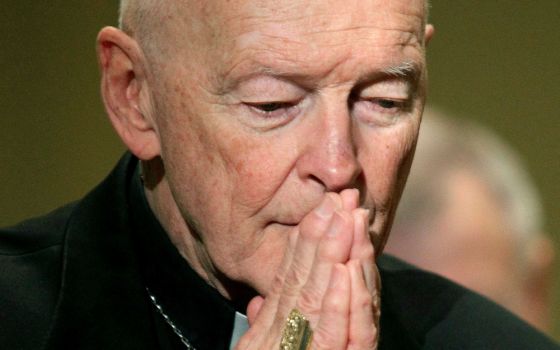

Former cardinal Theodore McCarrick (RNS)

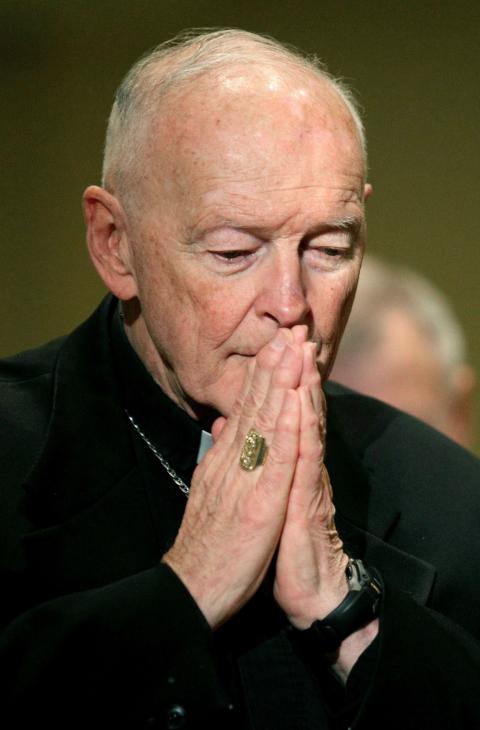

Former cardinal Theodore McCarrick (RNS)

The discussion of the Vatican report on ex-Cardinal Theodore McCarrick by the U.S. bishops at their annual fall meeting was sad but predictable — sad because the bishops failed to communicate that they understood the report's implications; predictable in that some bishops defended John Paul II against the report's finding that the pontiff shared culpability in the McCarrick case.

The report, released Nov. 10, acknowledged that despite it being known that McCarrick was sleeping with seminarians, he was promoted to the Archdiocese of Washington and made a cardinal by Pope John Paul II.

It would have been better for the bishops to acknowledge the pope’s failure and argue that if he were alive today, he would be apologizing for his mistakes. In their 45-minute public discussion of the report, followed by 90 minutes of talking privately about it, they did neither.

Bishops are reluctant to criticize John Paul’s record of appointing and promoting bishops because most of them were appointed the same way by the same pope. To acknowledge his failures would open the possibility that they, too, were selected through a defective process that stressed loyalty over other factors.

“It can't be a bad system; it selected me,” would be the attitude of most bishops.

Only Bishop Mark Brennan of Wheeling-Charleston suggested that the process should be improved. He proposed giving 30 to 60 days at the end of the process for people to comment on a candidate before his appointment was finalized. That way, he said, “We might avoid appointing someone to the episcopacy who did not deserve it.”

The tone of the meeting was set by Archbishop Christophe Pierre, the papal nuncio, who did not even mention McCarrick’s name in his address to the bishops. What Americans needed to hear instead from the pope’s representative was an apology for the failure of his predecessors and the Vatican hierarchy, who not only did not deal with McCarrick’s abuse but promoted him.

The president of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, Archbishop Jóse Gómez of Los Angeles, did better in introducing the discussion by saying that it “shows that the tragic outcome was not the result of a single failure but rather resulted from multiple failures across many years.”

Those failures were fed by clericalism, he acknowledged. The culture of clericalism limited the church’s “ability to discuss abuse with honesty and integrity," he said. "It left other brave voices feeling isolated when they called out the sins of abuse.”

Advertisement

Gomez acknowledged the failures of the past without naming names — for example the three New Jersey bishops, all now deceased, who knew about McCarrick's abuse of seminarians and said nothing.

But Gomez stressed spiritual reform, rather than institutional reform, because he believes “we have already made important steps addressing the institutional failings that led to this sad tragedy of Theodore McCarrick.”

Gomez urged the bishops to have a personal relationship with Jesus in prayer. This relationship would then be the foundation of their relationship to each other in the common task of building the kingdom of God.

“Individually and collectively, we apologize for the trauma caused by those who commit abuse and any church leader who fails to respond with compassion and justice,” he said.

He expressed “deep sorrow for the victims and survivors of abuse” and said the bishops are committed “to holding the church and each one of us as bishops accountable on the ways we have failed in our responsibilities to our Lord and to the people of God.” He said the bishops were ready “to continue on our path of repentance, purification and reform.”

Likewise, Archbishop William Lori of Baltimore called on the bishops to spend an hour each day in prayer and reparation before the Blessed Sacrament, together with some form of fasting or penance each week.

But while acknowledging the need for spiritual reform, some bishops called for more accountability and institutional reform.

Pointing to the gifts of money McCarrick gave to clerics and organizations, which have led to suspicions that he was buying influence, Bishop Michael Olson of Fort Worth called for the recipients to be named.

“We have to give an accounting to the faithful for this, we have to respond to their questions,” he said. This is necessary “for the continuing of our conversion, for the continuing of the purification of our church and its transparency.”

Bishop W. Shawn McKnight of Jefferson City argued that reports like the McCarrick report should come as a matter of routine when accusations are made rather than only when they are forced by public demand. He also urged a greater role for the laity, particularly those with relevant skills, in conducting investigations.

The peculiarities of the McCarrick case prompted calls for looking at the abuse with new eyes. Noting that the abuse of adults and seminarians is often overlooked, Archbishop Bernard Hebda of St. Paul and Minneapolis called for the bishops “to reach out to our priests and seminarians to allow them to speak about their experiences and about whatever it might be that would prohibit someone from coming forward with allegations.”

Others bemoaned the division among the bishops the case has caused. Cardinal Blase Cupich of Chicago cited the letter of Archbishop Carlo Viganò accusing the pope of ignoring McCarrick’s abuse and calling for his resignation.

“We have to make sure that we never again have a situation where anyone from our conference is taking sides in this with the Holy Father or challenging him or even being with those who are calling for his resignation,” Cupich said. “That kind of thing really has to cease.”

Cupich also called on the bishops to meet with survivors of abuse, to encourage them to come forward.

Victims “were intimidated; they thought they would not be listened to because of the power structure and so on,” he said. “The more that we listen to victims and make it public that we are meeting with victims, as the Holy Father does on a regular basis, the word will get out there that we are on the side of victims. We will learn to have our hearts moved the more we listen to victims.”

It is a mistake to focus on either spiritual or institutional reform in the absence of the other. Both are needed to deal with the tragedy of sexual abuse of minors or adults. The report requires much more study and discussion by the U.S. bishops and the whole church in order to discern the correct path into a better future.