Los Angeles Archbishop José Gomez, now president of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, holds his rosary Nov. 10, 2019, in a Baltimore hotel where he attended the U.S. bishops' fall general assembly last year. (CNS/Chaz Muth)

Next Monday, the U.S. bishops will begin their annual plenary meeting with a big difference: Due to COVID-19, they will not be gathering as they have in recent years at the Marriott Waterfront hotel in Baltimore, but will hold a virtual meeting spread over two days.

COVID-19 is not only changing the manner of their convocation, it should also inform the recalibration of the bishops' stance toward the culture, a recalibration that should be the central focus of this year's meeting.

Last spring, the bishops — like most Americans — did what was asked of them. We suspended in-person liturgies. We went without the solemn celebrations of Holy Week. We closed our schools. In many cities, bishops and other clergy developed better relations with their civic leaders as all saw the clamant necessity of combating this horrific threat to the common good. When we all started reopening our society, we did so cautiously and in concert with public health requirements.

In short, the bishops learned something about the common good, about what we owe to one another, and how, in a pluralistic society, the common good can be sought even while enormous differences on issues remain.

As the bishops prepare to welcome a new administration in Washington, they need to be guided by that concern for the common good and abandon the culture-warrior approach that has plagued their public posture for too long.

President-elect Joe Biden is now the most prominent Catholic in the country. He speaks powerfully about how important his faith is to him, usually in the context of the monstrous suffering he endured, losing his wife and daughter in a car accident, and then his adult son to brain cancer. He also ran a campaign that highlighted some of the pillars of Catholic social teaching — human dignity, the common good, solidarity — and he did so explicitly. He is not coming at the bishops looking for a fight.

Yes, from a Catholic perspective, the president-elect is grievously wrong in his support for liberal abortion laws. We Catholics are rightly horrified whenever any group of people, no matter how powerless, is denied legal protection. The taking of innocent human life is wrong no matter the circumstance. But how a politician approaches the issue of abortion is not the only thing to know about them.

Biden is a man of decency who is wrong, not an indecent man, and if the bishops welcome his presidency in the same nasty, combative way they welcomed that of President Barack Obama, they will live to regret it. They need to abandon the zero-sum, legalistic approach they have followed in recent years, as if the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops is an arm of the Becket Fund.

They should look to lower the temperature in the culture wars and reach some accommodations with the Biden administration on the issues where they disagree with the president and work together on the many, many issues about which a Democratic administration is much closer to the teachings of the church than the outgoing administration was, starting with immigration and climate change policy. If they don't, many of the next generation of Democrats will continue to put the words religious liberty in scare quotes and prioritize abortion rights above those rights enumerated in the First Amendment.

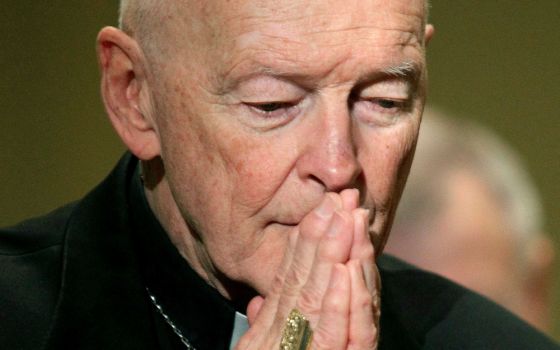

Of course, no issue will hang over this meeting like the McCarrick report. Some of their brethren were not candid when they were consulted about Theodore McCarrick's misdeeds by the nuncio, Archbishop Gabriel Montalvo, in the spring of 2000. It was ridiculous to think an inquiry of McCarrick's protégés constitutes an investigation, but that does not let those bishops, now deceased, off the hook in terms of assigning moral responsibility for McCarrick's rise.

The system failure the report catalogues was comprehensive but, like all such failures, needed only one or two brave, fiercely honest bishops to stand up and say, "No." All the bishops need to pledge themselves to act responsibly in the implementation of sex abuse policies, no matter who gets ensnared in any allegations and investigations.

Advertisement

One of the issues that the report minimizes is money. We may never know if there were bustarellas involved in the McCarrick episode: The reason crooks use cash is because you can't trace it.

But we know that McCarrick was the principal actor at the Papal Foundation, which raises money from big donors for papal charities. The entrance fee is $100,000 to become a member, but you get to go to Rome every year and meet the pope. Before his downfall, McCarrick accompanied the group each year. You can guess whether it was the access or the charity that animated McCarrick the most. The Papal Foundation should be shut down. McCarrick may be gone, but the modus operandi remains the same.

Another aspect of the money issue is that McCarrick took large checks from people and deposited them in accounts he alone controlled. Bishops should only, repeat only, accept checks for the diocese or a legal nonprofit with a board of directors like Catholic Charities. All such boards should have laypeople as well.

McCarrick was never one to spend money on fancy food or clothes. He only craved power. The ability to spread money around Rome or Poland was surely done with an eye toward his ecclesial advancement.

The bishops might also discuss with the nuncio how we could improve the consultation process that determines whether or not a candidate is suitable to become a bishop or be promoted to a larger see.

Before 1893, there was no apostolic delegate in the U.S. to compile ternas (lists of candidates) for vacant sees. The process of naming a new bishop began with a first consultation that involved the priests of a diocese, who gathered and compiled a terna of three names that was sent to the metropolitan. He, in turn, convoked a meeting of all the bishops of the province and they also prepared a terna. Both lists were sent to the Propaganda Fide office in Rome where the final terna was crafted for presentation to the pope.

Why not bring back this process, and include a terna from the nuncio? There is no guarantee it would have prevented someone like McCarrick from being named a bishop, but it might have. Besides, wider consultation might prevent other types of disastrous appointments: McCarrick is not the only bishop to have ruined a diocese, and sexual crimes are not the only form of episcopal malfeasance.

The conference of bishops is deeply divided, as is the nation. But they also share uniquely powerful bonds upon which to draw if they get serious about rebuilding communion, a communion to which they are pledged by their oath of office and the church's theology about the office of bishop. That oath and that office, as well as the facts that they are all men of a certain age, all received similar training, all spend their days saying the same prayers and reading the same Scriptures, all these should make it somewhat easier for them to find a basis for renewed communion. They could provide a model for the rest of the country.

If the bishops sincerely wish to try to build communion one with another, they will also need a shared goal. The experiences of 2020 point toward the obvious candidate. COVID-19 has exposed the way poverty and race afflict our health care delivery system. The summer of protests highlighted the systemic racism that continues to afflict our culture and our society, denying Black Americans opportunities the rest of us take for granted. Poverty remains the greatest abortifacient in our society. The election pointed to the limits of politics at this moment of time. What can unite these different experiences?

Just last month, Fr. Michael McGivney, founder of the country's most famous mutual aid society, the Knights of Columbus, was beatified. The bishops should commit the entire church in the U.S. to addressing poverty and racism for the next few years, not only by lobbying for certain policies from the government, although that is essential. Not only through statements that invite reflection and conversion, although those can help.

No, the bishops need to start by examining our own institutions, from parishes to schools to hospitals, to see how they can be used to provide a hand up to those on the margins of society, using the 19th-century mutual aid societies as a model. Such an effort would not only align the church in the U.S. more closely with the Gospel, but it might help bishops, the church and the society overcome the divisions that plague us.

[Michael Sean Winters covers the nexus of religion and politics for NCR.]

Editor's note: Don't miss out on Michael Sean Winters' latest. Sign up and we'll let you know when he publishes new Distinctly Catholic columns.