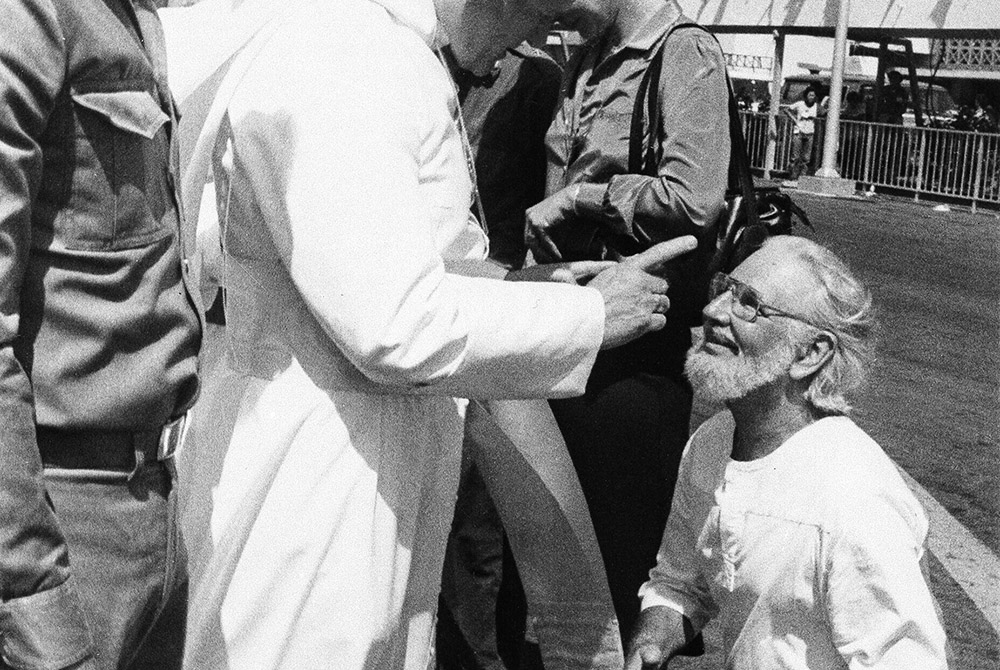

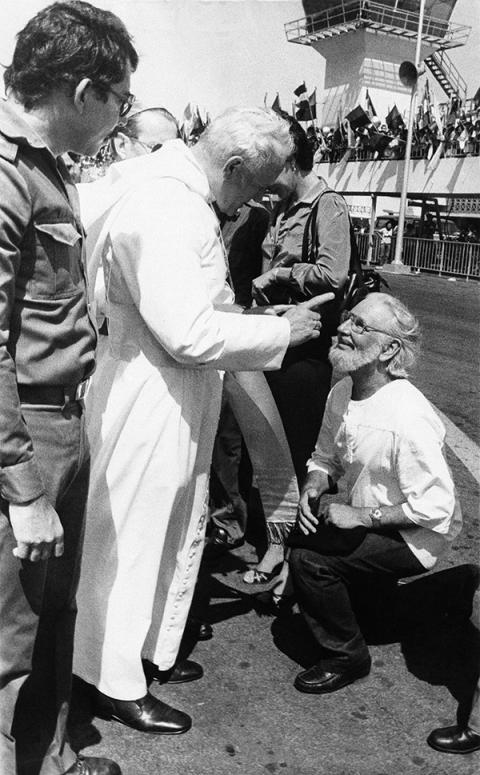

Pope John Paul II wags his finger at Culture Minister and priest Ernesto Cardenal, during welcoming ceremonies at the airport in Managua, Nicaragua, in this March 4, 1983, file photo. (AP photo/Barricada, File)

Ernesto Cardenal has died, at age 95, and once again the image of him kneeling before Pope John Paul II is making the rounds. It was 1983, and Cardenal, a priest, knelt on the tarmac at Augusto Sandino International Airport in Managua and tried to kiss the ring of the visiting pontiff. John Paul scowled, wagged his finger in Cardenal's face, and told the priest to cease his disobedience to church authorities who had ordered him to quit his post as minister of culture in the revolutionary government.

In that moment, seemingly frozen in time, the revolutionary priest and the reactionary pope offer us an icon of a sclerotic church afraid of a world in which the church is taking new forms.

Cardenal grew up in a wealthy Nicaraguan family but fled political persecution after a failed coup in the 1950s. He studied at Columbia University in New York, then joined the abbey at Gethsemani, Kentucky, where he schmoozed with Thomas Merton. But he went back to Nicaragua in 1965 to found a church on a remote archipelago on Lake Nicaragua. The priest trained painters who depicted the region's natural grace in primitivist style, beginning to earn income for their art.

Cardenal's Sunday sermons were conversations with his dirt-poor parishioners, which he recorded, transcribed, and eventually published in several volumes of The Gospel in Solentiname. If you want to know why the pope was angry at the airport, read those dialogues. As the poor read and reflected on the Gospel, they envisioned a Magnificat-like revolution, what Felipe, one of the principal characters, one Sunday dubbed "to flip the tortilla."

In this March 4, 1983 file photo, Daniel Ortega flanks Pope John Paul II who wags his finger at Culture Minister and priest Ernesto Cardenal, during welcoming ceremonies at the airport in Managua, Nicaragua. (AP Photo/Barricada, File)

The tortilla flipped in 1979, when the Sandinista National Liberation Front drove out the U.S.-backed dictator. Yet unlike the revolution in Cuba two decades earlier where the revolutionaries persecuted the church for having sided with the rich, in Nicaragua the church was welcomed into the revolutionary fold precisely because priests like Cardenal had encouraged laypeople to embody their faith by actively participating in the insurrection.

In a region where the church had long served to provide ideological justification for conquest and control, it was not just a social revolution, but a religious one as well. That's why the pope was worried.

As a cabinet minister, the poet-priest tried to make a go of encouraging cultural expression, but with the revolution soon under attack by the Contras, pressure mounted to turn poetry into propaganda. War-induced austerity finally closed his ministry in 1987, and Cardenal retreated to his shady home in Managua's Los Robles neighborhood, writing poetry that increasingly took on science rather than politics.

He toyed with returning to Solentiname for good, but the idyllic community, now a thriving artists' colony, was torn by internal conflicts over land ownership. It was easier to remain in Managua, where conversations with his neighbor, former Vice President Sergio Ramírez, eventually led them to break with former President Daniel Ortega to form the Sandinista Renovation Movement. Still a Marxist, Cardenal was left waiting for a better revolution. In one of his poems he wrote:

Solentiname

was like a paradise

but in Nicaragua

paradise is not yet possible.

Cardenal was wonderfully complicated, extraordinarily talented, and blessed with a visage–white hair sticking out from under a black beret — that became one of the region's most recognizable brands. He didn't suffer fools gladly, a fact I quickly learned when I interviewed him in his Managua home a couple of times. Amid the ferns and prolific paintings, he would simply dismiss questions he found inadequate. He had no need to convince me of anything, his life and work spoke for him. And, unfortunately for me, a nosy journalist, he wasn't interested in dishing dirt on other religious leaders who attacked him. In a way, they were beneath any need for him to comment.

He could display patience at times. I heard him read his poetry in Berkeley in the 1970s, when he was on one of his tours drumming up solidarity for the insurrection. In a conversation afterward with the audience, he spoke only Spanish, though he was perfectly fluent in English. At one point, his translator was having a hard time with a particular phrase. Cardenal repeated himself, in Spanish. The translator kept on bumbling it, until finally the priest leaned over and whispered the correct English translation in his ear.

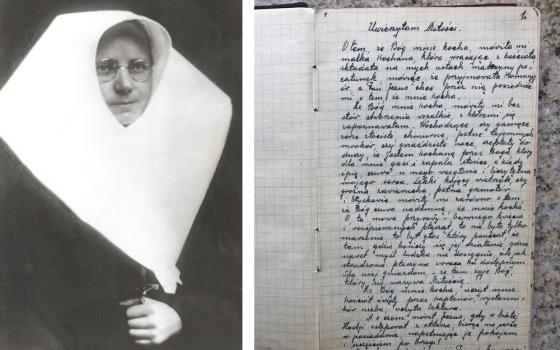

Nicaraguan poet, priest and Reina Sofia Prize winner, Fr. Ernesto Cardenal, speaks during a celebration for his 90th birthday at the National Theatre Ruben Dario in Managua, Nicaragua, Jan. 27, 2015. (CNS/Reuters/Oswaldo Rivas)

I translated for him a few times in Managua when I accompanied church groups to visit him, and it was terrifying. He used words with precision, as a poet is wont to do. And he would speak only in Spanish. So when I didn't translate his words into the exact English he preferred, Cardenal would look at me from under his beret and slowly repeat in Spanish exactly what he had said, daring me to have another go at it.

The revolution he firmly believed in didn't get translated in practice as he had envisioned it back in Solentiname. That led Cardenal back to his poetry, where he could more precisely control tone and nuance.

Until his death on Sunday, he remained a firm believer in revolution, and in the need for the church to play its part in flipping the tortilla. Yet unlike that iconic moment on the tarmac almost four decades ago, the church today isn't quite so afraid of his vision. A year ago, Pope Francis quietly restored Cardenal as a priest. It wasn't a sign that Cardenal had changed. If anything, it was a sign that the church had changed, that Francis is trying against all odds to help the church overcome its fears and open itself to be evangelized by the poor and others at the margins of global power, people for whom Ernesto Cardenal was their priest and their poet.

[Paul Jeffrey is a journalist who lives in Oregon. He lived in Central America for many years.]

Advertisement