Bishops and priests attend the opening Mass of the Synod of Bishops on young people, the faith and vocational discernment at the Vatican in October 2018. (CNS/Paul Haring)

Editor's note: Eugene Cullen Kennedy, who died June 3, 2015, was one of the most prolific and insightful observers of the Catholic Church in the modern era. Following is the second of two pieces on the clergy culture and the sex abuse crisis that were part of a larger work underway when he died. The manuscript, last worked on in January 2015, was shared with NCR by his widow, Sara Charles Kennedy, who noted the happy coincidence that Kennedy's date of death was the same as that of St. Pope John XXIII, whom he greatly admired. John XXIII died in 1963. The longer manuscript was lightly edited for clarity and divided into two parts. The first part, "The purgatory of the sex abuse crisis," was published yesterday.

Joseph Campbell used to say, "The latest re-enactment of Beauty and the Beast is taking place right now at the corner of Fifth Avenue and Forty Second Street." As we all re-enact some myth in our way of living, working, and loving, so we may better understand how and why, despite promises and programs, we seem not to gain any real ground in resolving the sex abuse crisis in the Church. The answer may be found in identifying the guiding myth of hierarchical bureaucrats.

Hierarchs re-enact the myth recounted in the Odyssey of the ancient Greek King Sisyphus who was punished "in the underworld by having repeatedly to push a rock to the top of the hill, only to have it roll down again." One interpretation of this myth is that Sisyphus must unendingly suffer the death he did not suffer adequately the first time he faced it. (The Oxford Companion to World Mythology by Donald Leeming, Oxford University Press, 2005, p. 356)

The great rock of the sex abuse scandal keeps rolling back down the hill on the vast hierarchical bureaucracy that has certainly not yet died adequately, and has, in fact, dodged death in multiple ways, including its failure to kill off the elements within it that, perhaps unconsciously but nonetheless truly, enable and provide varied safe houses for clergy who abuse children sexually.

Bureaucrats in the Curia exchange knowing glances when they hear that a new cohort of reformers is marching on Rome. As Popes come and go, they purr like the Roman cats who have watched pontiffs passing through while they remain forever. Previous efforts to reform the Curia have not been successful and, in fact, the basic structure of the Church's founding, collegiality, that offers such promise as a structure suited for the Space/Information Age, survived in name only under Pope Saint John Paul II and Benedict XVI.

These great figures had also cooperated in suppressing this collegiality, an ancient Catholic notion that remains threatening because it replaces the strict monarchical hierarchy with a structure compatible with the deepened understanding of the universe and the cosmos, the developments of Evolutionary Theology, and of the unity of human personality with its implications for understanding religious belief and its relevance to all human experience, especially the integration of sex and the deepest of our intimate commitments to each other.

These popes also ended the authority granted to local churches to deal with their own problems at their own level. Collaborating on Apostolos Suos in 1993, John Paul II and then Cardinal Ratzinger reduced national conferences of bishops to dependent groups whose members could neither initiate nor write pastoral letters, such as that on nuclear war written by the American bishops that in the early 80s stirred a national debate on the most serious moral issue of the age, unless they first submit them to Rome for approval.

That unhealthy suppression of the collegiality of bishops may seem unrelated to the hard-to-kill sex abuse problem but these elements are intimately connected through the way in which the papal action preserved and strengthened the centrality and control of Roman hierarchs and the power of the Curia over the entire Church.

Why, for example, did it take Pope Saint John Paul II so long to recognize the crisis festering in the Legionaries of Christ and their patron of perversion founder, Father Marcial Maciel, whom that pope often praised and supported? Why was the Sex Abuse Crisis so long ignored and then dismissed as an American problem or a function of the inflamed imagination of the press? Why, despite fits and starts at dealing with it, does the sex abuse crisis exist like an ecclesiastical iatrogenic disease unidentified and untreated by the hierarchy? Why does the curia resist self-reformation and how successful can Pope Francis be unless he has the cooperation of the world's bishops in carrying out this task and restoring the collegiality and other fundamentals of Vatican II that his predecessors did their best to destroy?

The sex abuse crisis, like death, taxes, and the biblical poor, remains with us because the central source and oxygen supply of its existence, corrupted hierarchical structures, has been dangerously and tenuously propped up by Pope Saint John Paul II and Benedict XVI.

The sex abuse crisis abides because the complex hierarchical culture refuses to die and refuses to investigate itself in order to identify the flagrantly immoral elements within it.

U.S. bishops cast their votes on the Charter for the Protection of Children and Young People at their meeting in Dallas in June 2002. (CNS/Bob Roller)

Hierarchy's last stand, 2002

In the United States, in response to the explosion of the clerical sex abuse scandal in Boston, America's bishops met in Dallas in June 2002 and passed draconian standards for priests ("One Strike and You're Out"). But, asserting their hierarchical instincts, they claimed reflexively their own special power and privilege by declaring themselves exempt from the regulations they just passed for the priests beneath them.

[Editor's note: Pope Francis recently promulgated rules that hold bishops accountable for not only abuse but also covering up abuse. Particular applications of the new statutes will be discussed by the U.S. bishops in June.]

That signaled that, although the bishops might throw some egregiously guilty priests to the lions of the law and the courts, they would fight to protect the hierarchical complex, its assets, its property, and its leadership. They missed the irony in their promise of transparency; its real meaning was that you could see right through them and their ongoing efforts at retroactive control of the crisis.

At Dallas, the bishops formed a panel of distinguished lay Catholics to look into the problem although they provided no budgetary support for the number of witnesses this group would need to talk to or for the professional time they would give to this work. Ultimately, the hierarchical reflex reasserted itself and the bishops neutered by largely ignoring and then largely disregarding this board whose members included Judge Ann Burke of Chicago and lawyer Robert Bennett of Washington, D.C.

Cardinal Edward Egan offered limited hospitality in New York, refusing even to make arrangements for Mass for them. An irritated Cardinal Francis George of Chicago asked a commission member, "Why are you trying to destroy the Catholic Church?" What the hierarchs seemed to want was the ability to claim they had a panel of distinguished Catholics looking into the Sex Abuse Crisis. They did not, however, want the panel to discover anything.

The Herod Effect

The "Herod Effect" describes the hierarchical safeguarding of the Church's worldly goods even at the price of sacrificing some of its children to the hardly tender mercies of its sex abusing clergy. This has been the signature response of hierarchs, following the advice of their own lawyers, to the sex abuse of children by priests and religious on every continent for the remedy of which other lawyers assail the Church for damages rather than work together toward understanding the problem that has, transferred to the legal system, become a third thing.

The first concern of lawyer counseled hierarchs, therefore, has not been healing the victims as much as keeping whole, as accountants say, the hierarchical Church and, as we might also say, all its works and pomps. As long as the crisis has been translated into legal terms by both the hierarchy and the personal injury lawyers, its adversarial character only deepens and, as it is moved almost entirely into lawyers' offices and courtrooms, the chance of coming to grips with its causes becomes obscured and the opportunity to resolve it permanently more remote.

The reason that we seem always in the Middle of this crisis that cries out for but resists closure is that, without anyone's really noticing it, the sex abuse crisis has been translated almost completely into legal rather than pastoral language. This has left lawyers battling with other lawyers over compensation or defending against compensation for Sex Abuse. This has taken on a life of its own that, while seeking to obtain or deny monetary payments for victims, remains on the outside of the effort to identify the nature and causes of the Sex Abuse Crisis itself.

Advertisement

The bureaucratic style

Hierarchical bureaucrats do not deal straightforwardly with problems because solving them quickly would leave them staring at empty desk surfaces, and waken them from their dream of earning ecclesiastical battle ribbons through ask-no-questions paper shuffling. The very idea of solving problems such as that of clerical Sex Abuse makes bureaucrats anxious because it threatens their livelihood, their privileged life-style, and the validity of their guiding beatitude, "Blessed are the Bookkeepers for They Shall Become Bishops Someday."

The reaction is always the same. Laypeople perceive its incongruity but church leaders do not: the hierarchical Church reacts in the first instance to protect itself and its power rather than to examine itself to discover and rid itself of the psychological conditions and the failure of moral vision that have enabled the sex abuse crisis to continue within itself. The hierarchical Church is compromised by its self-interest in survival and its hesitation to name this infection and to deal once and for all with the damaging side-effects of its hierarchical presumptions.

One can tell that the hierarchical Church remains highly defensive about examining the dynamics of a structure that is of human rather than divine origin. The hierarchical bureaucracy has resisted real reform successfully for centuries, taking unto itself the Sex Abuse problem that it denies, misinterprets and blames on others. It also abandons the abused in the New Purgatory, the painful Middle in which they must repeat endlessly their victimization in a grim bureaucratically designed Groundhog's Day.

To borrow the rhythms of Winston Churchill, we have not reached the End of the Sex Abuse Crisis nor even the beginning of the End but we have reached and are stalemated at the beginning of the Middle of the Crisis. We will make progress through this purgatorial Middle only if Church leaders — the human persons who serve — focus on the realities that have contributed to the infection of erotic disorder that is haphazardly nourished by perennial hierarchical strategy and tactics.

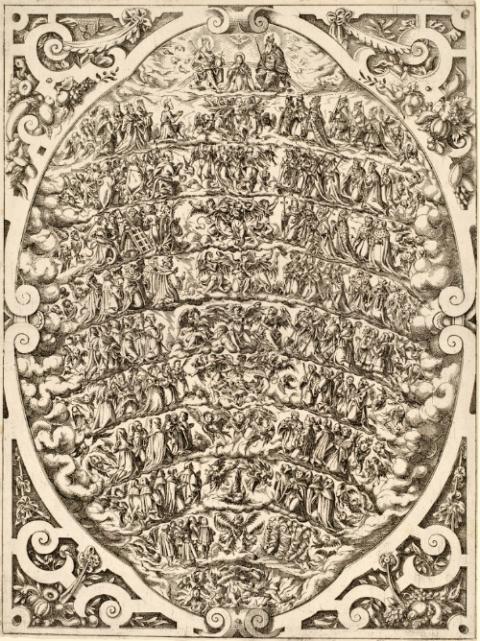

These leaders now have the opportunity to examine the way they perceive the cosmos and whether the structures whose patterns were based on a simplified view of the earth below and the heavens above adequately reflect reality. Hierarchy grew out of this projection of the star laden skies above and the abiding earth below on the basis of which the divided and graded model of the universe and the kingdoms within that universe was drawn. The dawn of the Space/Information Age and the richness of the developing evolutionary theology reduce the usefulness of the hierarchical template in our understanding not only of the universe but of human personality as well.

"The Hierarchy of the Heavens" (1579) by Jost Amman (National Gallery of Art)

No matter the hierarchical hands raised against the incoming tide, the future has already washed over the present. The Church, much like a family, is trying desperately to adapt to a shift in the way of life it had counted on as unchanging and virtually unchangeable. It has been torn, instead, between an attempt to return to a familiar and comforting past and an eagerness to enter the Mystery of an already present but not well understood future. Breaking cleanly out of the Middle of the Sex Abuse Crisis demands that the leaders in the Church surrender the style that made the Sex Abuse Crisis possible and, so far, its resolution impossible.

These leaders could begin by a review of the effect of the hierarchical pattern on its teachings about human personality and human sexuality. The hierarchical pattern that divided the universe into the heavens above and the earth below also divided the person into good and bad parts, pitting the flesh against the spirit as it viewed the will rather than the imagination as the great engine powering religious belief and human behavior. It has perpetuated the border war between flesh and spirit and supported the dominant role of male over female in the Church.

The church and celibacy

The Church could begin to identify but one of the elements that leaves us ever in the Middle of the Sex Abuse Crisis by moving beyond the hierarchically derived notion that chastity is higher than marriage and that forsaking sex is superior to celebrating it. Church leaders could take a modest but helpful step in the right direction if they stopped referring to celibacy as the "treasure" or "crown jewel" of the priesthood that not only cannot be changed but cannot be discussed either.

These leaders are capable but do not feel free to immerse themselves seriously and objectively in understanding and identifying celibate dynamics. They exist in the powerful unconscious and unnamed truths about celibacy in the life experience of those who must accept it in order to pursue their sacramental calling.

In the psychological study of American priests whose results were reported to the bishops in April, 1971, one of the principal findings was the large percentage of priests who were psycho-sexually immature. They looked like adults but their psycho-sexual development lagged far behind their actual age.

Many of these men were children internally and were understandably bewildered when they left the cold storage lockers of the traditional seminary system to find their sexuality stirring, flooding them with low level desires for erotic experience for the first time in their lives. They had had no trouble accepting the requirement of celibacy in the abstract. After ordination, living in the world instead of the cloistered seminary, they found it exciting and puzzling to experience even shallow and protoplasmic sexual feelings.

Many of this cadre of under-developed priests, as they were designated in this 1971 study for the American bishops, had never had a deep relationship with a woman other than their mothers who, in an area still not studied thoroughly, played a major role in the pre-Vatican II culture in supporting and emotionally sustaining the sons who were priests. The mothers of priests were highly regarded in that culture and shared a saying that gave them peace and delight, "You never lose the son who becomes a priest," meaning, the mother never lost him to another woman, as happens in the normal order of things to transform and mature men who are not bound to be celibate.

The clerical culture, an ecclesiastical version of an exclusive men's club, also offered enormous emotional support to priests who enjoyed good times like the most innocent of boys, but boys nonetheless, during the high period of the pre-Vatican II Church when clerical culture flourished. This camaraderie was not unhealthy and was, in many ways, what made celibacy a bearable condition for them. It did not, however, advance the inner growth of those who were psycho-sexually immature. They were good boys, in good standing in the wonderful then highly honored, privileged and excuse-endowed Clerical Culture.

Vestments are seen in Grapevine, Texas, Sept. 19, 2018. (CNS/Tyler Orsburn)

The 1971 research revealed many well-developed priests, of course, as well as a substantial number who were developing in a healthy way. Still, most priests did not find celibacy a state of grace that enabled them, as its theological rationalization claims, to give themselves more fully to all their people. Celibacy was something to which they adjusted. Celibacy was easier for men like the psycho-sexually immature who had never felt any strong attraction to marriage or experienced any radiation of the erotic in their lives.

Many such priests confessed garden variety sins, if they were sins at all, of having what were termed "impure thoughts" and admitting on the slide rule of sexual sin how often and how much they had "taken pleasure" in them. These resembled the confessions of children rather than mature adults. The best strove manfully and largely successfully to follow the measures that their confessors and retreat masters prescribed to triumph over these unbidden impulses. These were not, however, the sins of grown men.

Immature priests were simply not prepared for the engine of growth to start rumbling within them, picking up at their by-passed or hesitantly entered puberty. When they entered parish life, a world warm with human feeling substituted real if fragmented human growth for abstract intellectualized growth. It is not surprising that for many their budding attraction was to boys who matched their own internal pre-adolescent state. Most of these priests did not understand what had suddenly taken hold of them and drawn them into a bizarre, overwhelming and fugitive life within the permeable yet protective ecclesiastical culture.

This is not an uncommon human challenge and can be observed in many American men who have no connection with any church. Henry James, for example, describes the complexity of achieving self-awareness in his late 19th century novel, The Awkward Age. As James's biographer, Leon Edel, summarizes the situation, Nanda will not judge harshly the character Aggie "a continentalized virgin who runs wild the moment she is 'safely' married." Nanda, in James's words, explains that "Aggie's only trying to find out what sort of person she is." (Henry James: The Treacherous Years: 1895-1901, New York, Philadelphia, Lippincott, 1969, p. 258)

Finding out what kind of person they were became the challenge for many under-developed priests who experimented primitively with sex in ways tragic for them and their victims. Yet many healthy priests explored the same question when, after Vatican II, they examined the unsatisfactory rewards of friendships forged in Clerical Culture compared to the depth of relationships they found in healthy women who were not their mothers. Many of these priests sought permission to marry not, as is often supposed, for sexual gratification as much as the fulfillment they experienced in an intimate relationship with a healthy woman.

Many of those who became sexual abusers were abused themselves by the hierarchical/clerical universe in which they trained to become priests. The seminary system did not do much for healthy candidates who were able to do great good as priests, but it did do something for the under-developed candidates who brought their low level of psycho-sexual development with them into the seminary.

The classic closed universe of the pre-Vatican II seminary confirmed them in their incomplete growth, rewarded them for being passive and obedient, and, although they studied sexual sins in moral theology classes, they remained preternaturally innocent, their psycho-sexual development frozen before it began.

The hierarchical system, therefore, made them in its own image, glorifying them in one way but leaving the poorly developed to enter the priesthood unprepared to experience, understand, and in many cases, to control the sudden surge of sexuality, the delayed adolescence that left them vulnerable to the furtive sexual experiences that they sought out, too often with the young people who trusted them.

A priest holds an image of Mary in Medjugorje, Bosnia-Herzegovina, in 2011. (CNS/Paul Haring)

The women in the church

One of the enduring characteristics of the hierarchical system and its Clerical Culture is its fear of the feminine, except, of course, the Blessed Mother and their own mothers. Mothers of priests were, in fact, an integral part of the universe of Clerical Culture in which they occupied places of privilege and in which, by their ongoing influence over their priest sons, they stabilized them, that is, rewarded them with affection and attention for never growing beyond being the best little boys on the block.

In some cases, their never-modified psychological attachment to their priest sons bound the latter by invisible emotional bonds to the psycho-sexually under-development that left these "good boys" unprepared for the confusing impact of their budding sexuality that correlated with their first extra-familial human contacts with real people, as the telling shorthand captured it, in parish life. They were drawn, as noted, in a way that puzzled and disturbed many clerics, to the children who, as noted, mirrored their own inner incomplete growth.

Honored and beloved in the clerical culture in which the first greetings between priests upon touching base with each other was often "How's your mom?" priests' mothers created the pattern of relationship with women that their priest sons followed in their subsequent relationships with all the women they would meet in the world they entered after they left the seminary.

Those who made it to the hierarchy as bishops reinforced the pride these mothers took in their sons but did not necessarily motivate them to loosen their emotional bonds with them. They were and are frequently uncomfortable with women, ill at ease, in fact, in any relationship in which they may be emotionally vulnerable. They are at ease, understandably as one considers their training and the characteristics that identified them as good episcopal material, when they are firmly in the saddle, even if they are genial and easy riders.

A thorough exploration of the dynamics of clerical culture, including its rooting in seminary isolation and its relationship with women, is an essential step in breaking out of the Middle and finally resolving the sex abuse crisis.