Bishop Raymond Hunthausen walks in St. Peter's Square after having attended the Sept. 27, 1965, working session of the Second Vatican Council. (AP Photo/Gianni Foggia)

Archbishop Raymond Hunthausen, who died July 22, didn't set out to be a thorn in the side of John Paul II's reaction against key elements of the Second Vatican Council. In fact, when Rome abruptly clamped down on the archbishop in the 1980s, branding him a troublemaker, he was largely unknown outside his Seattle diocese, let alone as a firebrand. At home, his notoriety was largely as a peace activist who protested nuclear weapons in Puget Sound. It was a far cry from the Vatican's suspicion that he was a church outlaw.

In the years I reported on bishops' meetings, Hunthausen was another face in the black suited ranks, never divisive, disdainful or distressed. This was not a bishop with an edge toward his superiors looking for ways to fight the power. His protests against Trident missiles in Puget Sound were rooted within the church, in Catholic pacifism which Vatican II helped revive. He was the picture of the modest, ground-level pastor of pastors.

This portrait became more sharply etched in my reporting when the roof fell in on the archbishop. He was accused of violating a list of official Catholic practices, from letting divorced, remarried Catholics take Communion to inviting gays and lesbians to meet in his cathedral and kindling talk of women filling all roles in the church.

In the background, it was widely reported that Hunthausen's nuclear protests rankled the Reagan administration, which had pressured Rome to stop him.

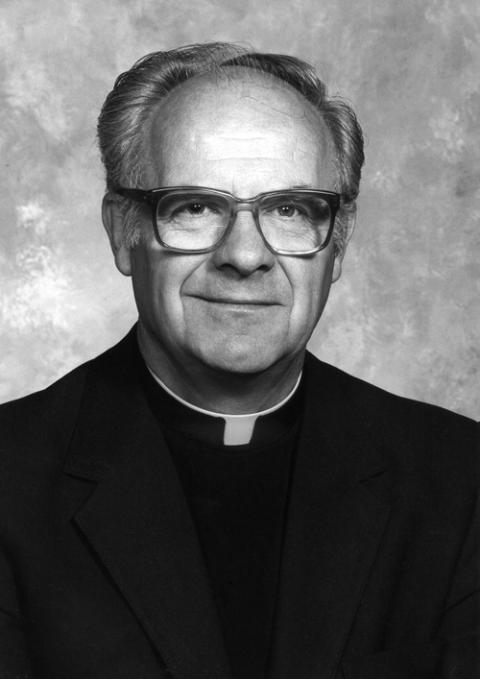

Retired Archbishop Raymond Hunthausen of Seattle, pictured in an undated photo (CNS/Courtesy of Archdiocese of Seattle)

The result was an attempt at shaming and shackling that left the archbishop under a cloud of disfavor, with his functions severely limited. Rome assigned Bishop Donald Wuerl to take over half of Hunthausen's duties, leaving the archbishop out to dry. His fellow bishops uttered not a word of challenge to the Vatican's action. John Paul II and his enforcer, Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, delivered a highly visible blow to liberalizing elements of Vatican II they and other leading church conservatives opposed.

Hunthausen was accused of being a weak, undisciplined leader who had trampled on church teaching. A solid portion of his archdiocese strongly rejected that judgment. They spoke of him as a loving pastor who cultivated faith and loyalty to the church.

The awkward, painful episode had dramatized the vast chasm between strict constructionists who insisted on taking the council's writings as modest adjustments to earlier doctrine which needed trimming and even reversal, and the creative romantics like Hunthausen who embraced the council as a movement, an ongoing challenge to integrate implications into parish and public settings.

My own limited observations on this drama await Frank Fromherz's much fuller treatment in his newly released biography of Hunthausen, A Disarming Spirit: The Life of Archbishop Raymond "Dutch" Hunthausen. From my vantage point, however, the archbishop bore certain defining marks of the "movement" people.

He awakened to the council's reminder that primary authority resided in the whole "people of God" and that enlightened personal conscience was the arbiter of truth for the individual. His grounding was widely seen as grounded in the Gospels, church teaching and a conscience nurtured by prayer. The council's dramatic opening to the world led him to apply that mission to his surroundings.

The council's elixir of conscience and renewed teaching led him to take steps to fulfill Vatican II's inspiration in ways that responded to the needs of the people he served. It seemed the loving thing to open Communion to divorced and remarried Catholics, to welcome gays and lesbians to church celebrations and to extend hope to women seeking ordination. And similar things. It must have felt like the conscientious thing to do, not in defiance of the church but in keeping with Vatican II and the longings of people in front of him.

I saw his departures from conventional ministry, therefore, as an extensions of that expansive, dynamic movement he had embraced. The charge that he sought to rebel against church orthodoxy or the supreme authorities of the church never gained much credibility among those who knew and watched him. He was, above all, a pastor deeply imbued with movement from council inspiration.

His demeanor reminded me of a bishop out of folklore, full of charity for those whose circumstances cried out for mercy. He was for his admirers an extraordinary Ordinary, though he aspired to no such thing.

At his passing, he was compared favorably to Pope Francis. They did seem to share similar compassion and inclination to go with the flow of that council dynamism.

Advertisement

But there was a striking difference, resulting either from outlook or strengths. Hunthausen was comprised of both deep faith and conscience, and the courage to follow implications of that council spirit to which he felt called. He went to Puget Sound knowing the price of protest, in terms of putting his life and reputation on the line. He and Francis both spoke loudly for the poor, for peace, for humility and forgiveness. Francis as pope has so far concentrated on the message. Hunthausen's low-key activist nature was far more inclined to apply such prophetic words to problems around him, even at considerable risk.

[Ken Briggs reported on religion for Newsday and The New York Times, has contributed articles to many publications and written four books.]