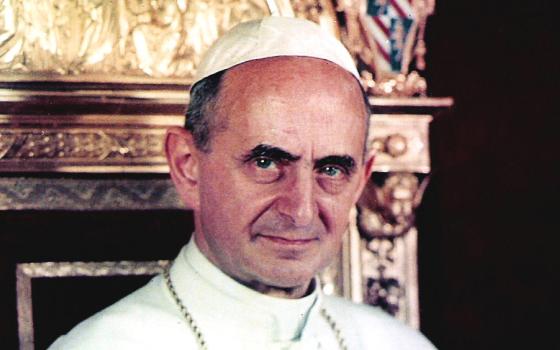

Pope Paul VI in 1963. His most famous encyclical, “Humanae Vitae” (“Of Human Life”), was published July 25, 1968. (Vatican City official photo/Creative Commons)

Fifty years ago, Pope Paul VI issued an encyclical that shook the Catholic Church to its core by declaring that every use of artificial contraceptives is immoral. The document, "Humanae Vitae" ("Of Human Life"), was a shocker because many Catholics had hoped the pope, with the widening availability of the pill after its appearance in 1960, would open the way for Catholics to use birth control.

The encyclical continues to be controversial, with the hierarchy, including Pope Francis, supporting it while most Catholics ignore it.

When the encyclical was published on July 25, 1968, the response from Catholic moral theologians was overwhelmingly negative. Although they liked many things in the encyclical, the universal prohibition against artificial contraception was not something they could support. They noted that almost all other Christian denominations approved of contraception and that the papally appointed commission to study the issue had recommended a more open position.

The opposition of theologians was not just behind closed doors. It was very public in scholarly articles, op-eds, news conferences and signed petitions. Both Catholic and secular media covered the dispute extensively. Disagreements in the Catholic Church over sex made good copy.

Nor were theologians the only ones to disagree. Some cardinals and bishops distanced themselves from the pope, pointing out that the document was not infallible teaching and that each person had to follow their conscience. The German bishops issued the "Declaration of Königstein" that left to individual conscience of lay people whether to use contraception or not.

And much of the laity worldwide did follow their own consciences. Polls have shown that the overwhelming majority of Catholics do not accept the hierarchy's teaching that all use of artificial contraceptives is immoral. In 2016, the Pew Research Center found only 8 percent of American Catholics agree that using contraceptives is morally wrong. Catholic couples felt that they understood the situation better than celibate males.

It is uncertain how many Catholics left the church over this teaching, but it is clear that even more stayed, continued to go to Communion, and simply ignored it. This was a remarkable change for Catholics who had deferred to the clergy on moral and doctrinal teaching. It gave rise to the concept of "cafeteria Catholics," Catholics who picked and chose which teachings they would accept.

Some in the hierarchy blamed dissenting theologians for leading the people astray. While it is true that the public debate eased the consciences of some Catholics, the vast majority of Catholic couples were making up their minds on their own. In fact, studies found that increasing numbers of Catholics were already using contraceptives in the 1950s.

Rather than shoring up the authority of the hierarchy with the laity, "Humanae Vitae" undermined it. In the laity's mind, if the church could be so wrong on this issue, why should they trust the church in other areas?

"Humanae Vitae" was not just a dispute about sex. It quickly became a dispute over church authority.

Advertisement

Cardinal Karol Wojtyla of Krakow, Poland, was a member of the papal commission studying the question of birth control. The man who would become St. John Paul II missed the last meeting where a majority of the commission voted in favor of changing church teaching. As a result, his position on birth control was not well known. We now know that he supported the minority position and wrote directly to Paul VI supporting the retention of the church's prohibition against artificial birth control.

If his opposition to birth control had been widely known, would he have been elected pope? Certainly, any cardinal who supported changing the church teaching and voted for him regretted it later.

John Paul understood that the debate over "Humanae Vitae" was as much about authority as sex. He was scandalized by the opposition of theologians and bishops to papal teaching. As a product of a persecuted church, he understood the importance of church unity. Once elected pope, he launched an inquisition against moral theologians who had spoken out against the encyclical. He was ably assisted in this effort by Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, whom John Paul made head of the Vatican Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith. Ratzinger succeeded John Paul as Pope Benedict XVI.

Since most of the theologians at that time were priests or members of religious orders, John Paul was able to use their promise or vow of obedience to get them under control. They were removed from teaching positions in seminaries and universities, forbidden to write on sexual topics, and told to profess their acceptance of the encyclical. The training of priests was put into the hands of those who stressed papal authority and following rules rather than the reforms of Vatican II.

Likewise, "Humanae Vitae" became a litmus test for the appointment of bishops. Loyalty to papal authority became the most important quality looked for in a potential bishop, trumping pastoral skill and intelligence. Over the almost three decades that he was pope, John Paul remade the hierarchy into a body that had little creativity or imagination in implementing the reforms of the Second Vatican Council. Rather, they looked to Rome for leadership and stressed the importance of following rules.

Today, many in the hierarchy are claiming that "Humanae Vitae" was prophetic in its conviction that contraceptives led to the separation of sex from procreation and therefore to conjugal infidelity, disrespect for women, gender confusion, and gay marriage. But the controversy was never over the encyclical as a whole; rather, it was over its prohibition of every single use of artificial contraception. To say that contraception caused all of these other problems is absurd, an insult to all the good people who have used contraceptives at some point in their lives.

How should the church deal with this problem? It is probably impossible for it to simply admit it was wrong. The church is not very good at that. What it could do is say that abortion is a far greater evil, and anyone who might be tempted to have an abortion should practice birth control. The church should also stop supporting laws forbidding the sale or public funding of contraceptives. These would be small steps in reversing a 50-year-old mistake.

[Jesuit Fr. Thomas Reese is a columnist for Religion News Service and author of Inside the Vatican: The Politics and Organization of the Catholic Church.]