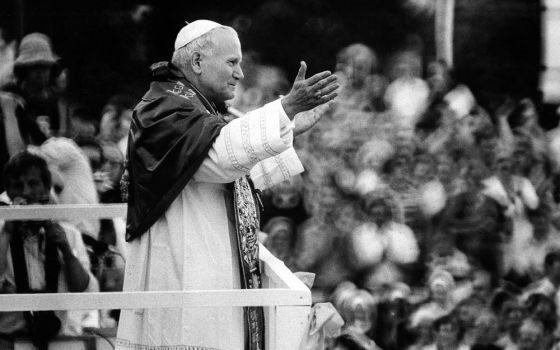

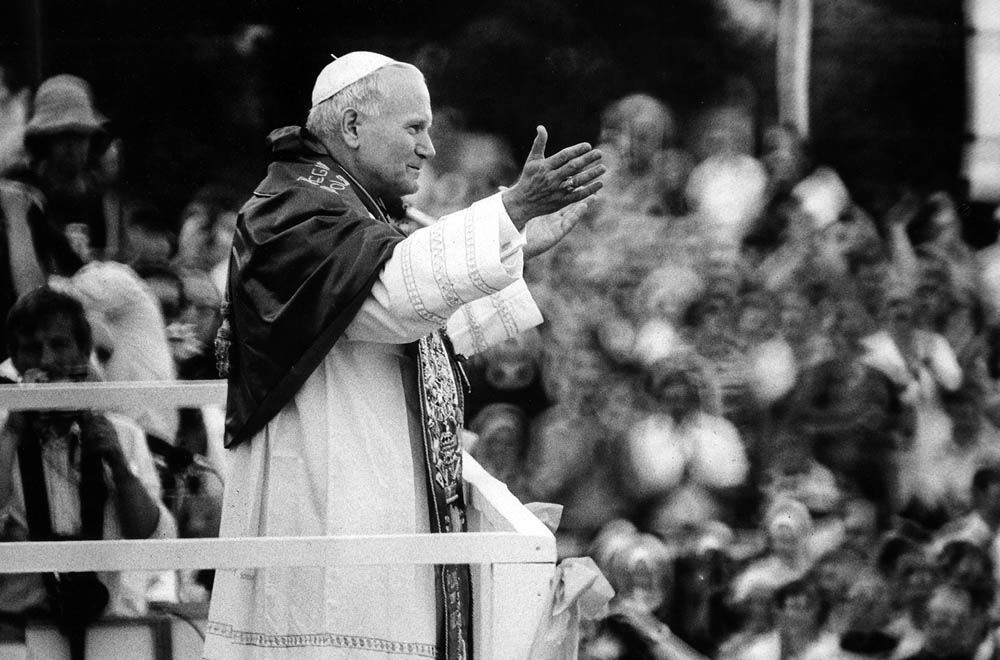

Pope John Paul II greets throngs of Poles waiting for a glimpse of their native son at the monastery of Jasna Gora in Czestochowa during his 1979 trip to Poland. (CNS/Chris Niedenthal)

In marking the 50th anniversary of Pope Paul VI's famous encyclical, Humanae Vitae, this July, the verdict of Catholic commentators in the U.S. and Western Europe was largely critical. However, powerful voices defended the document, particularly among the conservative church leaderships of Eastern Europe.

"We should remember the situation was very different from the outset in the West and in our region, where everything aimed against human life and the family was being blamed on communism," explained Fr. Piotr Mazurkiewicz, a former secretary-general of COMECE, the Brussels-based commission representing Europe's Catholic bishops. "Humanae Vitae was viewed as a counterweight to communist policies, a step in the church's defense of freedom and dignity, so there was very little resistance to it here — and this still defines some key contrasts today."

In Poland, there's been an additional reason for special attachment to Humanae Vitae, which reiterated orthodox Catholic teaching on marriage and rejected artificial contraception, insisting sex must be intrinsically linked with procreation.

The Polish church, strictly governed and disciplined, remains committed to the teachings of the revered St. John Paul II, whose philosophical influence on the encyclical, Paul VI's last of seven, is well documented.

Not surprisingly, Humanae Vitae has been vigorously defended at Polish church conferences and seminars as an expression of personal loyalty to the Polish pope, who proclaimed his pro-life message emphatically during nine visits to his homeland before his death in 2005.

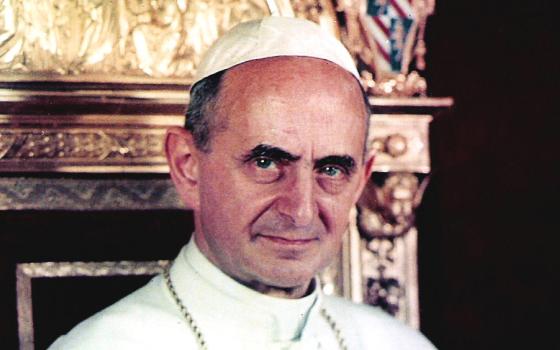

Archbishop Karol Wojtyla of Krakow, Poland, the future Pope John Paul II, receives the cardinal's red biretta from Pope Paul VI in the Sistine Chapel June 26, 1967.

Speaking at the Polish Bishops' Conference in Warsaw in June, Henryk Hoser, retired archbishop of Warsaw-Praga and a former president of the Vatican's Pontifical Mission Societies, said Paul VI had correctly foreseen, back in turbulent 1968, how contraception would "open an easy path to marital infidelity and a general collapse of standards."

Retired Archbishop Henryk Hoser of Warsaw-Praga, Poland, pictured at the Vatican in this Oct. 6, 2015, file photo. (CNS/Paul Haring)

Hoser, a trained physician who heads the Polish church's bioethics commission, noted that the church of the day had faced challenges from rapid demographic growth, as well as from social and cultural change, and concern over the natural world, which had spurred demands for universal birth control.

But Humanae Vitae identified how these would corrupt young people and erode respect for women, he insisted. In their place it had offered an "integral vision" of the person, and of self-giving, eternal and fruitful marital love, which was still justified given the injustices and inequalities highlighted by contemporary movements such as "#MeToo."

Fr. Pawel Galuszka, a moral theologian from John Paul II's former Krakow see, whose book, Karol Wojtyla and Humanae Vitae, studied the correspondence between Paul VI and his successor, thinks the then-cardinal's reliance on Catholic personalism was a novelty before the 1962-65 Second Vatican Council.

But the future pope also drew heavily on his empirical experience as a youth chaplain, which was given weight and depth in a Memorial z Krakowa, ("Krakow Memorandum"), which he later compiled with local theologians and submitted to Paul VI.

Once he became pope in 1978, Wojtyla determined to "fill the gaps" with a more comprehensive anthropological vision, Galuszka says, which was developed in his own apostolic exhortation, Familiaris Consortio (1981), and encyclicals Veritatis Splendor (1993) and Evangelium Vitae (1995).

Galuszka believes "noisy opposition" to this vision by some Western Catholics has overshadowed and drowned out the widespread support it received from 1968 onward.

This was especially marked in communist-ruled Eastern Europe, where abortion was freely available and parental and family rights were restricted, and where Humanae Vitae, though attacked as "reactionary" in the Soviet Union, provided Catholics with an important pro-life rallying point against communist injustices.

"Many people rejected Humanae Vitae without actually reading it.

They couldn't understand the questions the church was posing, let alone the answers it was offering."

—Malgorzata Glabisz-Pniewska

Malgorzata Glabisz-Pniewska, a senior Catholic presenter with Polish Radio, thinks John Paul II's passionate backing for Humanae Vitae was also deeply rooted in the wartime sufferings of Poland, where one of his closest collaborators, Wanda Poltawska, had witnessed newborn babies being gassed in Germany's Nazi-run women's concentration camp at Ravensbrück.

"When Humanae Vitae appeared, barely two decades had passed since World War II, when millions of Poles had died, so the defense of life in every form seemed absolutely imperative," Glabisz-Pniewska told NCR. "Since the whole issue of sexual ethics was largely unexplored in Poland, this pro-life stance could at times look extreme, particularly in other parts of the world which had escaped such sufferings, and saw abortion and contraception as expressions of freedom. Many people rejected Humanae Vitae without actually reading it. They couldn't understand the questions the church was posing, let alone the answers it was offering."

Polish perspectives have influenced the Catholic Church throughout Eastern Europe, where clergy exert a powerful presence, and where many Catholic leaders prefer the firm teachings of John Paul II over the reformist pastoral approaches advocated by Pope Francis.

When an exhibition was staged last summer in the European Union's House of History in Brussels, playing down the role of Christian faith and culture, Eastern European bishops' conferences were outraged by its claims that the church had "fostered discrimination" through its pro-life position, and "caused suffering to millions of women."

Several top church leaders have since praised Humanae Vitae for prophetically grasping the world's moral and social dilemmas.

In a May pastoral letter, Kazakhstan's bishops recalled the "truths contained in the 1968 encyclical," insisting all of human history provided evidence "that society's true progress depends to a great extent on large families."

Every divine commandment, they noted, also brought "a gift of grace which helps human freedom to fulfill it," which could be obtained "through constant prayer and frequent recourse to the sacraments."

In Belarus, the church's leader, Archbishop Tadeusz Kondrusiewicz of Minsk-Mohilev, believes Catholic teaching on contemporary evils has, despite all controversies, remained rightly consistent.

"Half a century ago, in the cause of so-called sexual revolution, an attempt was made to reject the Gospel as the foundation of European culture," Kondrusiewicz told Catholics at Budslau in July. "Humanae Vitae offered an answer to this moral pathology and simultaneously a call to permanent conversion. It showed how, to build a civil order, human life had to be upheld in the light of God's creative plan and the eternal, supernatural order."

In nearby Slovakia, a June conference at the church's Christianity Foundation explored the implications of Humanae Vitae's "rejection by the world," while in Croatia, the World Federation of Catholic Medical Associations met in May with Archbishop Vincenzo Paglia, president of the Vatican's Pontifical Academy for Life, and offered "a response to relativization of the sacredness and dignity of human life and procreation caused by social movements since the 1960s."

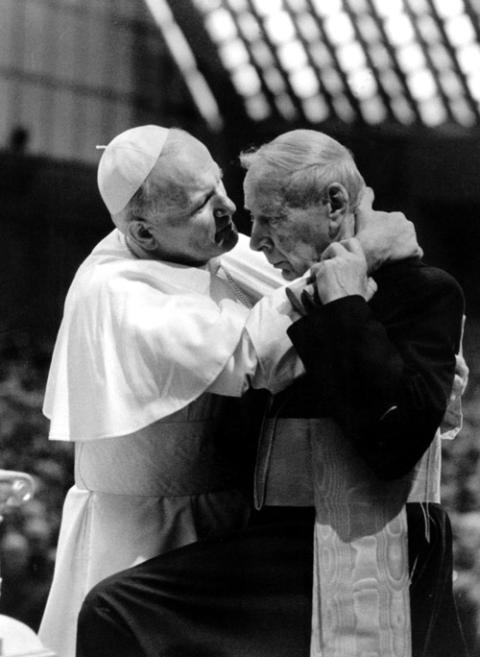

Newly elected Pope John Paul II and Cardinal Stefan Wyszynski of Poland embrace at the Vatican in this 1978 photo. (CNS/Arturo Mari)

Mazurkiewicz thinks support for Humanae Vitae in Eastern Europe has been vindicated by the passage of time.

In the 1970s, the Polish church's leader, Cardinal Stefan Wyszynski, even went some way to persuading his country's communist regime about the social and demographic perils of abortion, and to inducing some Communist Party members to support the church's pro-family stance.

Half a century on, the justifications have piled ever higher, Mazurkiewicz insists — for a document which, in its Eastern European reading, warned against objectivizing women, and against pressure from the United Nations and powerful nongovernmental organizations for drastic population curbs in the world's poorest regions.

"If the church had approved contraception, this would have been used by political rulers and international organizations to promote inhuman restrictions on population growth — the 'new form of ideological colonization' which African bishops warned against at the last Rome synod," he said. "In Western culture, the Christian vision of humanity may no longer be predominant — while atheist, anti-Christian notions have entered the Catholic community as well. But the church can speak with a clear conscience today when recalling that it opposed these things from the beginning with Humanae Vitae."

Even in traditionally Catholic Poland, secularizing pressures are being felt as never before, with surveys confirming widespread opposition to aspects of church doctrine against a background of falling vocations and Mass attendance.

Barely one in three Poles declare full support for Catholic moral teachings in areas such as premarital sex and contraception. And while opposition to abortion remains strong, 90 percent of young people attending pre-marriage courses in some dioceses already live together, according to Fr. Wojciech Sadlon, director of the Polish Church's Statistics Institute.

Some Polish prelates are eager to confront the problems.

In May, Poland's Catholic primate, Archbishop Wojciech Polak of Gniezno, warned that many Catholic parishes risked turning themselves into "ghettos," composed of "self-satisfied people who isolate themselves from others."

Archbishop Wojciech Polak of Gniezno, Poland, attends a youth meeting in early June 2015, in Lednica, Poland. (CNS/Jakub Kaczmarczyk, EPA)

Meanwhile, Archbishop Grzegorz Rys of Lodz urged his church to revise its pastoral approach and begin taking much greater account of individual needs.

Although 94 percent of surveyed young people cited the family as their "most important value" in his own central diocese, Rys pointed out, only 38 percent had cited the Christian faith, while only six percent saw anything wrong with contraception and barely 10 percent claimed any "strong involvement" in church life.

"We've turned God into a collection of notions, abstractions and definitions," he told journalists in May. "Everyone is delighted with declarations that the family is the key value for young people. But they're not expressing this value in a religious way. ... We are clearly losing something here, with serious implications."

Criticisms of Humanae Vitae have appeared in Poland's secular media, with some commentators echoing Western views that the encyclical impeded the struggle against HIV/AIDS, was never accepted as part of a sensus fidelium among Catholics and presented little more than a collection of attractive but impracticable ideals.

Mazurkiewicz rejects such criticisms.

Even in conservative Poland, the church's teaching has evolved in the half-century since Humanae Vitae, Mazurkiewicz says, away from the demographic and social focus of Wyszynski and his contemporaries, towards a greater engagement with scientific and medical knowledge, and a more holistic pastoral approach.

"But when we talk of ideals, we have to distinguish between those inherently unrealizable, and which the church has never proclaimed, and those which reflect something fundamental to God's intentions," he told NCR.

"We know sin exists and the world can never be perfect. But this isn't an argument against Christianity — just the opposite, it's a fundamental part of Christian teaching. Some critics contend people should be able to exert their will over everything, including their own fertility. What Paul VI reminded us was that there are some important areas where God is in control and human will isn't enough."

Some Eastern European prelates think their church has a mission to show the way for confused and demoralized Catholics in the West.

Preaching in late June at celebrations to close the 1,050th anniversary of his country's first Catholic bishopric in Gniezno, its bishops' conference president, Archbishop Stanislaw Gadecki of Poznan, said Europe was looking to Poland's robust Catholic faith to save it from "flabby totalitarianism."

Consumer society shared the same aims as communism, Gadecki insisted, seeking to manipulate human beings through a "powerful bureaucratic and media system, and a language modified by propaganda."

Europe's system of parliamentary democracy no longer relied on violence, but on "a dictatorship of materialism" which sought, like communism, to "deprive the person of identity and responsibility."

"The European revolution began with a change of culture, which was turned into a tool of ideology whose energy is fully devoted to destroying traditional structures," he told Catholics. "In these new conditions, we must set the world an example of Gospel living, and externalize our faith in a new missionary engagement. This is the first and fundamental service our church must provide for all humanity."

Advertisement

Archbishop Marek Jedraszewski of Krakow told a Mass commemorating Humanae Vitae the same challenges which confronted Paul VI were now being posed by a deliberate manipulation of thought and language, which had fostered "gender ideology, reduced married life to mere pleasure, and replaced the idea of procreation with reproduction" — helped by an ubiquitous cocktail of alcohol and narcotics.

He traced the church's decline in countries like Germany, Belgium and the Netherlands to local opposition to Humanae Vitae and related teachings back in the 1960s.

Strident figures like Jedraszewski may have been heartened by Western expressions of support for Humanae Vitae, even in secularized Britain, where nearly 500 Catholic priests lauded the encyclical this summer as offering a "proper 'human ecology,' " and nearly 200 young lay Catholics praised its "beautiful and prophetic" call to chastity in a July open letter.

But with Catholic clergy and laypeople clearly pulling in markedly different directions even within Europe, the church will have its work cut out when it comes to presenting a coherent, united set of teachings to fractious, skeptical societies.

Glabisz-Pniewska, the Polish Radio presenter, is unfazed.

In some areas at least, the church will always face challenges from medical advances and scientific novelties, she says. But there's much greater awareness among its leaders today of the complexities surrounding social and moral issues.

And while some bishops might not wish to admit it, there's also a fuller readiness to follow Francis in moving away from cold, bureaucratic rules towards a warmer consideration of pastoral needs.

"Even in countries like ours, the church knows there are areas of intimacy which have to be left to private consciences, and where individual circumstances must be considered over mere generalities," she told NCR.

"Here as elsewhere, the real problem facing the church isn't the lack of any single articulate voice on doctrine, but the simpler fact that most people no longer understand and accept that doctrine in the first place — and no longer see anything wrong in how they live and behave."

[Jonathan Luxmoore covers church news from Oxford, England, and Warsaw, Poland. The God of the Gulag is his two-volume study of communist-era martyrs, published by Gracewing in 2016.]