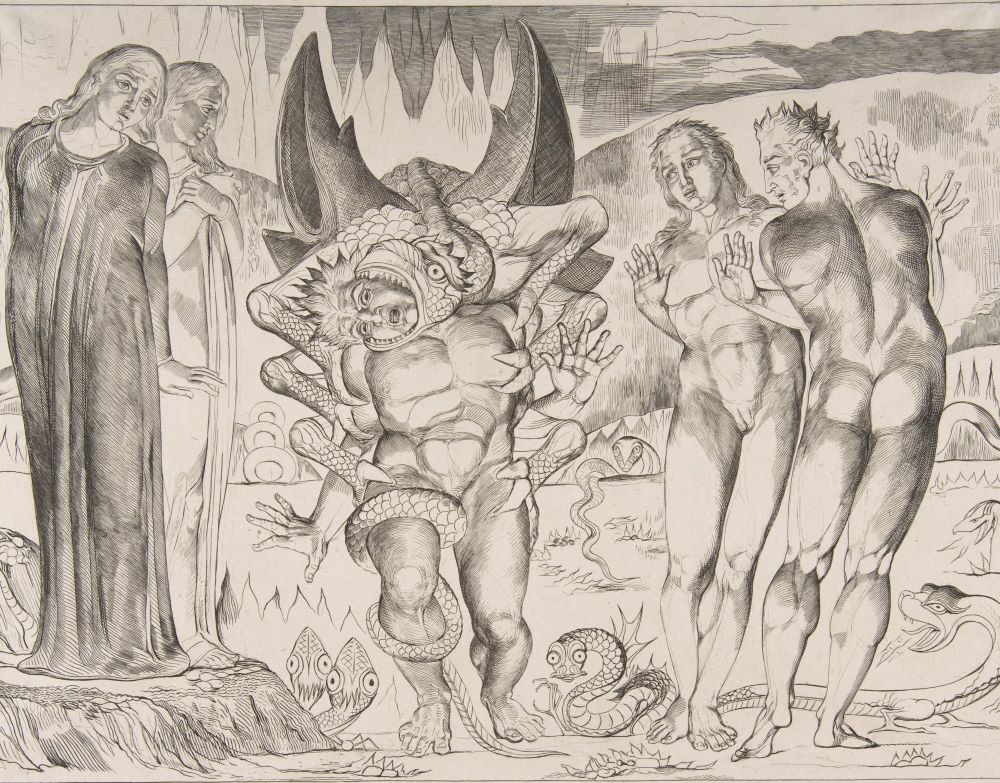

"The Circle of Thieves: Agnello Brunelleschi Attacked by a Six-Footed Serpent," engraving by William Blake, ca. 1825–27 (Metropolitan Museum of Art/Rogers Fund, 1917)

Until the COVID-19 pandemic, it had been decades since I'd thought much about the afterlife. As a kid, I was fascinated with stories by people who claimed to have received visions of Mary. My maternal grandmother lived with us and always had literature lying around about Marian apparitions, filled with testimonies like those of the six teenagers in Medjugorje, whose visions began in the 1980s when I was less than 10 years old.

On the surface I was devout, but deep down I had doubts. At bedtime I'd lay awake long after saying the words, "And if I die before I wake, I pray the Lord my soul to take," worrying about the finality of death. The news that there were people close to my age having regular chats with Mary eased my fears a bit. If Mary was real, that meant everything associated with her — heaven, God and Jesus — was real too. Then again, that had to include hell. After all, the Medjugorje teens said Mary gave them previews of the sorrows of damnation as part of her message.

My father wasn't Catholic or even religious. Did that mean, despite my dad's goodness as both a parent and a person, he'd end up somewhere different in the afterlife than us Catholics (my mother, my siblings and I), somewhere less than heavenly? And what about me? Had I already doomed myself, by age 10 or 12, with my little kid lies and petty sibling squabbles, my occasional hooky-playing and sleeping in on Sundays?

As I grew older, I stopped dwelling so much on the afterlife. Faith, after all, is more than just reward or punishment.

Advertisement

Then COVID came. The world became a bleak place, like something out of Dante, as the expression goes. During the long nights of lockdown, it was impossible to keep from worrying about mortality, to not fall, once again, into vicious anxiety-insomnia loops of questions about "what if" and "the other side." Who will COVID take next? Will it be any of my family? What if there's no chance to say goodbye? Is death the total end, or is there spiritual reunion after death? Is heaven or hell real? Or a God who divides us up in such places, even after all the suffering and division here on earth?

Then, a full year into the pandemic, a book came out that offered some surprising solace, one that assured me I'm not the only Catholic, practicing or lapsed, who struggles to piece it all together. To Hell with It: Of Sin, Sex, Chicken Wings, and Dante’s Entirely Ridiculous, Needlessly Guilt-Inducing Inferno, by Brevity editor-in-chief Dinty Moore, is a humorous look at Moore's Catholic upbringing, the seven deadly sins and hell — Dante's hell, specifically.

Reading a book about hell during a global plague runs the risk of feeling redundant. What makes this book different, however, is that, like most of Moore’s writing, it is packed with down-to-earth humor and clear prose. With devastating deadpan and straightforward, honest storytelling, Moore skewers the twisted theology that prioritizes belief in a punishing afterlife and inflicts psychic damage on people through guilt and fear.

"The Circle of Corrupt Officials: The Devils Tormenting Ciampolo," engraving by William Blake, ca. 1825–27 (Metropolitan Museum of Art/Rogers Fund, 1917)

Exploring Dante and Catholicism

The memoir follows Moore’s journey from his Midwestern working-class family roots through his struggles with depression to his own idea of paradise: a good life here on earth free of guilt and self-loathing. Each chapter begins with a stanza from Dante’s Inferno, accompanied with comics that highlight some of the more absurd and outrageous imagery from the Cantos (for one, the "ass trumpets" of Canto XXI). The book also includes adventures where Moore confronts the sins of gluttony, hoarding and waste. These take place at a competitive chicken wing eating contest in the hometown of Colonel Sanders and at the World's Largest Yard Sale, a four-day event held every August from Michigan down to Alabama.

Moore's wisecracking approach to Dante and Catholicism can be read partly as a reaction to the strict brand of Catholicism he was raised in. He went to parochial school in the pre-Vatican II 1950s, in the days of classroom lessons about limbo, “pagan babies” and the rote learning and circuitous logic of The New Saint Joseph Baltimore Catechism. Moore traded in faith for skepticism very young. "I don’t mean to brag here," says the adult Moore about the child Dinty, "but I learned to read early, and the Catechism was likely the first book I ever tossed across the room."

There's a similar rebellion in his description of Dante, whom he argues has played an outsized role in shaping people's concepts of the afterlife and sin. It might seem audacious or iconoclastic for another writer to take on one as famous — and indeed, influential — as Dante. But by parodying Dante's spiritual journey in The Divine Comedy with his own, Moore reminds us that Dante's epic was a work of creative vision, not theology.

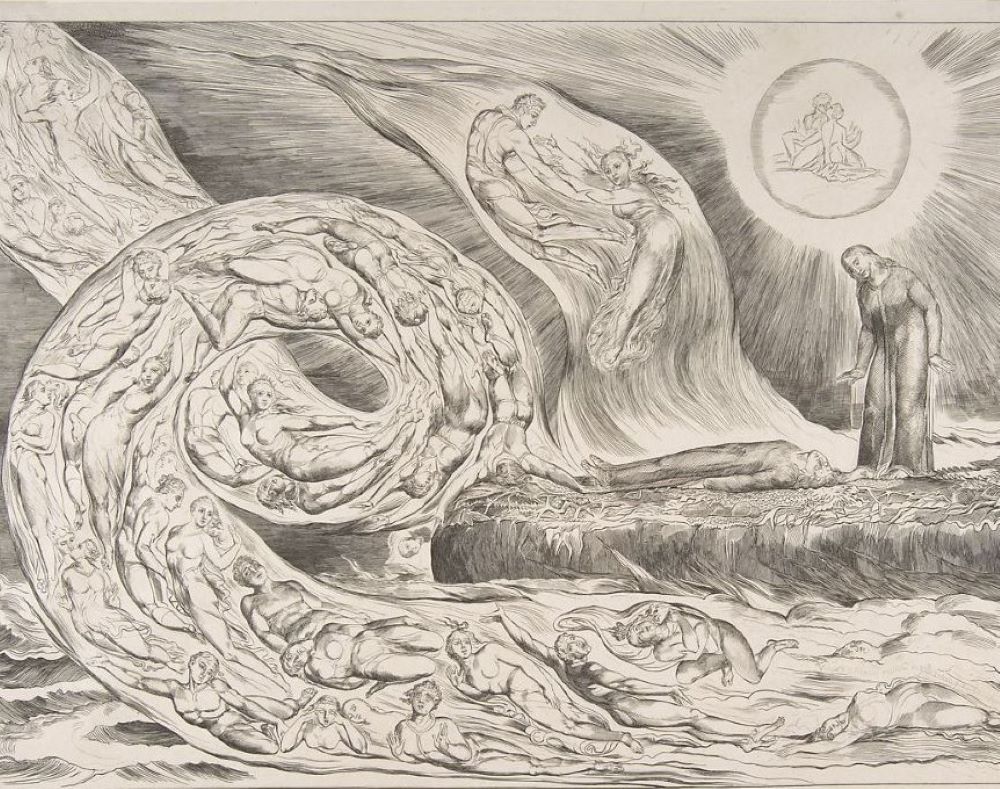

"The Circle of the Lustful: Paolo and Francesca," engraving by William Blake, ca. 1825–27 (Metropolitan Museum of Art/Rogers Fund, 1917)

As with many medieval believers, Dante was heavily influenced by St. Augustine, but his art was hardly the product of monastic-mystical contemplation or Marian visitation. Instead, he was your classic frustrated male poet walking the edge of creepiness with a million chips on his shoulder and an obsession with Beatrice, a local girl he barely knew.

As Moore writes, Dante was a municipal official "fully enmeshed in the political intrigue and petty bureaucracy of his time." Local disputes led to his banishment from Florence, and Inferno was the writer's attempt to settle scores. Casting the people who wronged him into a hell of his own creation, he used their real names and condemned them with forms of punishment so ghastly and absurd, our modern consciousness still draws from the imagery. "In other words," Moore writes, "the poetic masterpiece is at its most basic level a revenge fantasy, in rhymed tercets."

In tackling personal demons, Moore is no different. In his book's prologue, he writes about his lifelong "feelings of inadequacy" and his father's experience of laboring in a mechanic's pit day after day, drowning his self-loathing with alcohol much like Moore would come to do with food. Moore knows he's not alone, quoting the World Health Organization's statistic that 300 million people worldwide are living with depression. "All around me, I see people who walk day after day through their precious lives with a fearful cringe in their demeanor, as if the worst might befall us at any moment," he writes. "And if you believe those who claim to know the will of God, it very well might."

Moore plumbs the depths of this feeling in "The Hell Hole," a chapter on Dante's Seventh Circle of Hell, illustrated with photos of Moore's grandparents. Their smiles, jaunty postures and stylish fashions belie the pain of their lives. One grandparent died by suicide, another under unknown circumstances, another when her son (Moore’s father) was only 4. Moore's father served in World War II, failed twice at college and struggled with a stutter as well as alcoholism and the dead-end drudgery of his job. Moore's mother lived a long life, but the hardship of that life was apparent in a frequent expression of hers: "My Hell is right here on Earth."

I wonder how many people these days are echoing her sentiments.

"The Circle of Traitors: Dante's Foot Striking Bocca degli Abbate," engraving by William Blake, ca. 1825–27 (Metropolitan Museum of Art/Rogers Fund, 1917)

When the pandemic began, my siblings and I, who share the caregiving duties for our elderly parents, were separated from them and from each other. My mom called nearly every week with news of another lost friend or relative, none of whom she could say goodbye to or mourn in community. It was painful hearing the catch in my mom’s voice over the phone, to not be there for her in person. Then at Thanksgiving, Dad spent a week in the hospital, where he was alone and isolated while being treated with advanced congestive heart failure. He'd been hiding symptoms for weeks for fear of catching COVID in the ER. Dad got better, and he and my mom have so far evaded COVID, but others I know have been less fortunate. One childhood friend lost her father to COVID on Christmas Eve. Another had to say goodbye over FaceTime to her unconscious, COVID-infected grandmother, the woman who raised her, as she lay dying in isolation in a hospital.

Where has God been? Moore raises a good question when he wonders how much religious belief played into his family's sorrows and whether humans would be better off dispensing with belief in hell. "It isn’t helping," he writes.

A common argument for religion is that it provides comfort. But throughout the pandemic, many faith leaders have succeeded only in spreading the virus and exploiting the crisis for a political revenge not unlike Dante's. A Michigan Catholic school sued the state over mask regulations with the argument that masks hide faces "made in God’s image," thus the regulations violate religious liberty.

Others in the church have called for a rejection of the COVID vaccines on the grounds that they violate "pro-life" principles due to the use of stem cells in their making, even after Pope Francis received the vaccine and released a statement calling it "an act of love." Fr. James Altman in Wisconsin declared that those who imposed COVID safety protocols would burn in the “lowest, hottest levels” of hell. (He was removed from ministry after using similar language about Catholics who vote Democrat.)

Meanwhile, the COVID death toll continues to climb. Maybe Mrs. Moore was right — maybe hell is right here on Earth. Maybe her son is right too. Amidst the trauma of global plague, what good is a hell in the afterlife? Is it time to reconsider hell, given the hell time we’re living in? Instead of sin and salvation, wouldn’t it be better to focus on social justice, on alleviating the suffering on Earth while we’re alive? What would Dante, no stranger to plagues and political toxicity, do?

This year marks 700 years since Dante's death in September 1321. Italy has been commemorating the anniversary with events such as online exhibits and seminars. In May, legal scholars in Florence even held a retrial of the corruption case that got him banished and condemned to death in absentia. Who knows? Maybe the retrial set Dante's long-suffering spirit free. Maybe it's time the rest of us, like Dinty Moore, set our own souls free too.