Fr. Humberto Zúñiga Rogríguez tends to a congregation hard hit by COVID-19 in the Mexican border city of Matamoros. He was tapped to serve as a chaplain in COVID-19 wards after becoming ill with the disease and eventually recovering. He is pictured in front of the parish. (David Agren)

Editor's note: On Holy Thursday, Pope Francis prayed for the dead as well as for the priests, doctors and nurses who he said represented the "saints next door" during the coronavirus pandemic. National Catholic Reporter and Global Sisters Report are bringing the stories of Catholics in this crisis: those who have died, but also those whose service brings hope. To submit names of people for consideration for this series, please send a note to saintsnextdoor@ncronline.org.

Fr. Humberto Zúñiga Rodríguez ministers to the sick in the COVID-19 wards of this Mexican border city. But rather than asking for prayers or blessings, people routinely ask him for another kind of intervention.

"The first thing they tell you is: 'Padre, they're not treating me well.' 'Padre, they don't want to give me this medication,' " Humberto said on a sunny Saturday afternoon from the kitchen of his parish residence.

Many people also insist that they don't have COVID-19, which he said leads to the inevitable request, "I want to get out of here. Please tell them that, Padre."

Priests like Zúñiga work on the front lines of the COVID-19 crisis in Mexico, where the pandemic has claimed more than 80,000 lives — fourth most of any country in the world — though its impact has been receding slowly after peaking in August.

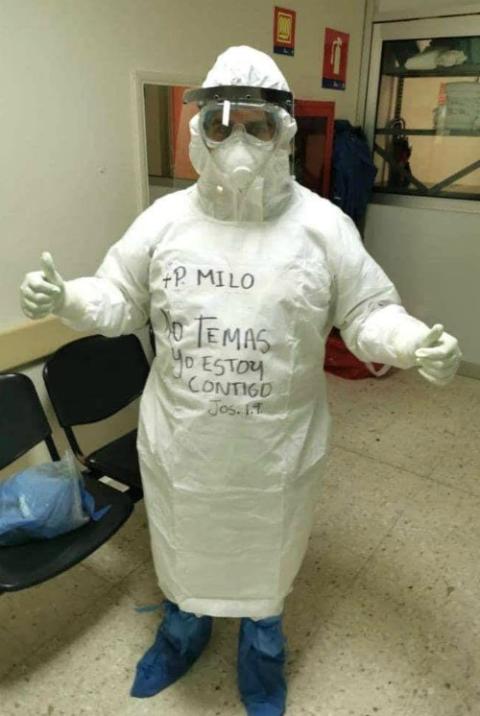

Fr. Emiliano Quezada dons personal protective equipment to work as a chaplain in COVID-19 wards in Reynosa, Mexico. He wrote a verse from Joshua 1:9, which reads, "Do not be afraid, I am with you." (Courtesy of Matamoros Diocese)

Zúñiga and a colleague, Fr. Emiliano Quezada, form the COVID-19 chaplain ministry of the Matamoros Diocese, which covers part of Tamaulipas state and is tucked into the extreme northeast corner of Mexico.

Dioceses around the world have appointed chaplains for COVID-19 wards – with priests risking their lives to minister to the sick and provide the sacrament of absolution. But Zúñiga brings a special insight to his work in the hospital: He contracted COVID-19 in June and recovered after spending 38 days in isolation.

"I think God prepared me for this," he told NCR in mid-September. "When the bishop named me as a COVID chaplain, I think the illness for me was preparation for this reality."

The chaplaincy experience — along with tending to a congregation hit hard by COVID-19 and now suffering its economic impact — has changed his pastoral outlook and brought about new approaches for reaching his flock.

"There have been tough times," Zúñiga said, referring to previous church persecution in Mexico — which predated his birth. "But to see the church have to close its doors to in-person contact was, for me, a jolt. I was ordained to attend to people, to celebrate Mass, to speak with people, but it's been six months and the situation has completely changed."

Zúñiga called his own experience of COVID-19 "preparation" for his eventual work as a chaplain. But it wasn't an easy experience. He spent two weeks bedridden at home with fever, diarrhea and other symptoms, and took three more weeks to fully recover.

Still, he would go online from his sickbed to pray the rosary with his congregation. He also used the time in isolation to take up new activities such as painting, cooking and even writing a book of meditations on the rosary.

Just 31, Zúniga spoke seriously of his faith and work as a priest — "I don't fake it or pretend to be cool or friendly," he said of his approach to chaplaincy — while offering candid observations on the pandemic and the community he serves as pastor of the Our Lady of the Assumption Parish.

Advertisement

His parish mostly includes factory workers, who toil for low wages in the many maquiladoras (factories for export) that operate in the borderlands. The factories reopened in early June after U.S. pressure was applied to keep continental supply chains operational.

Parishioners in Matamoros, like many Mexicans, greeted COVID-19 with suspicion. Talk of conspiracies surfaced, too — an old habit in Mexico, where the people are used to having politicians and the media spreading scare stories.

Many would tell Zúñiga: "It's an invention of the government. It's something that's a lie. It's a political plot." Then they started falling sick.

Quezada saw something similar in the city of Reynosa, 55 miles to the west of Matamoros. He counted 10 deaths in his congregation at St. Martin de Porres Parish, which also includes a population of factory workers and small merchants.

Quezada counseled parishioners showing symptoms to head for the hospital. But many responded with: "If I step foot in a hospital, I'm going to die."

Fr. Emiliano Quezada poses for a photo at the St. Martin de Porres Parish in Reynosa, Mexico, where the coronavirus pandemic closed factories and left thousands unemployed. Quezada has taken on additional duties as a chaplain in COVID-19 wards, where he prays for the sick and provides the sacrament of absolution. (David Agren)

As the pandemic took hold, national and state officials recommended measures such as quarantines, closing shopping centers and cinemas, suspending bus service and ordering cars off the road on certain days. Local governments imposed bans and alcohol sales, while a ban on nonessential activities stopped beer production — spawning a robust black market in suds.

But keeping COVID-19 at bay proved impossible. People were slow to take heed of what was occurring, the priests said. And many Mexicans headed out for Mother's Day — one of the biggest days on the calendar for families.

"People started going out for May 10, Mother's Day ... having fiestas, mariachis in their homes," Quezada said, "and this set off another wave of contagion."

Then there was neighboring Texas, where Gov. Greg Abbott loosened pandemic restrictions in the spring — setting off an outbreak in the Rio Grande Valley (just across the border from Reynosa and Matamoros).

Doctors in Matamoros say the binational population would cross the border with relative ease, even though Tamaulipas state officials set up a health checkpoint for southbound travelers. The uninsured still streamed south for medical services and to fill prescriptions cheaply. Doctors also reported a spike in cases as South Padre Island opened and people went north for vacations.

Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador also came to town in late August. Thousands turned out to inaugurate an urban renewal project — even though he told them to stay away — setting off another spike in infections, according to Tamaulipas health secretary Gloria Molina.

A medical worker prays in the Mexican state of Tamaulipas, where the Matamoros Diocese has started serving hospitals with chaplains. (Courtesy of Matamoros Diocese)

López Obrador largely downplayed the pandemic in the early days. He's subsequently sent out a stream of positive messages — "We've been able to tame the epidemic," he said in April — even as deaths kept accumulating.

The president, like his U.S. counterpart, doesn't wear a mask unless required. He's also spoken of moral virtue keeping COVID-19 away – while the country's coronavirus czar Hugo López-Gatell said in March of the president's reticence to stop holding rallies, "The president's force is moral, not a force of contagion."

López Obrador also pulled out a pair of prayer cards with images of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, which he called his "bodyguards."

Mexico's bishops have promoted both science and the spiritual, while also attending to material and emotional needs. Caritas has distributed thousands of care packages and established a listening line staffed by professionals. It later started a service for helping people find jobs or retrain — helpful in a country where the economy shrunk 17.3% in the second quarter and the government has spent less than 1% of GDP on pandemic assistance.

Zúñiga has seen the fallout in his neighborhood, where quarantines, factory closures and illness — along with inflated costs for medicines and oxygen tanks — have driven many to financial ruin.

"They've exhausted their savings," he said. "Many people had to close their micro businesses. Other people had to pawn things. Why? To be able to beat this illness."

Hospitals in Matamoros and Reynosa are still receiving COVID-19 patients, though the doctors say the number of cases locally is on the decline.

Fr. Humberto Zúñiga Rodríguez poses with health workers at a hospital in Matamoros, Mexico, where he works as a chaplain in the COVID-19 wards. (Courtesy of Matamoros Diocese)

Zúniga started his chaplaincy work in August. He and Quezada were provided personal protective equipment and training to use it properly and operate in a hospital environment.

The chaplains pray for patients, offer blessings and provide the sacrament of absolution "from the doorway" without touching anyone.

They also tend to medical personnel — more of whom have died in Mexico during the pandemic than in any other country — if asked.

"There's a lot of uncertainty on the part of the patients," Quezada said. "But I look at them with eyes of faith, eyes of hope. And my job is to encourage them, to give them some hope."

Chaplains haven't had much of a previous presence in hospitals and Zúñiga says he's found "priests aren't always welcomed" by the staff. Patients and their families also have mixed reactions, he says — though he persists and seems to have found a calling.

"Obviously, many [chaplains] are going to tell you about what's beautiful: the conversations, those who cry, those who say, 'Padre, pray for me,' " he said.

"As a priest, you don't look for this, but I've come across another face: the face of indifference," said Zúñiga. "People have to open themselves to grace. God will be there in one way or another, but if the person is closed, if the person rejects God ... they're not going to have the experience of God."

[David Agren is a freelance journalist in Mexico City.]