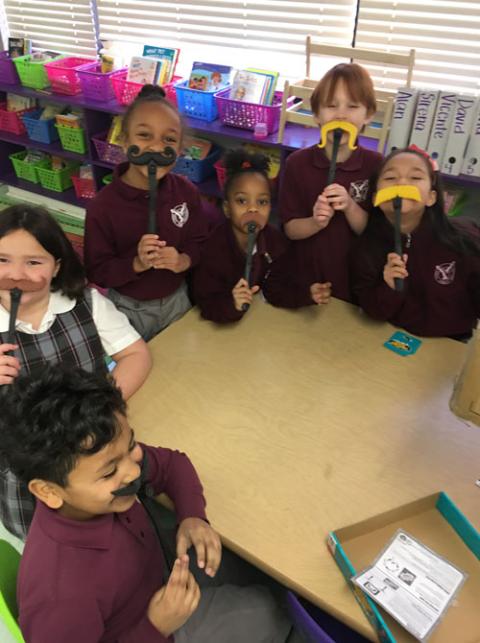

Students sing in class during the 1963-64 school year at St. Joseph's Catholic School, the first year white students attended the school. (Jack Hamilton/Courtesy of Salvatorian Archives)

When 12 new students reported for their first day Sept. 3, 1963, at St. Joseph's Catholic School in Huntsville, Alabama, neither they nor their classmates knew they were making history, but they were.

St. Joseph's became the first racially integrated elementary school in the state of Alabama, when the entering white pupils took their seats alongside 106 African-American students already enrolled. This historic change was accomplished without fuss or fanfare. The mother of one white student described her child's reception as "not just peaceful, but warm, welcoming and comfortable."

While most examples of school desegregation in the nine years after Brown v. Board of Education were the result of federal court orders, white parents voluntarily registered their children at St. Joseph's, knowing they would be part of a racial minority. Fr. Mark Sterbenz, then pastor of St. Joseph's Mission, downplayed the significance of the school's unique "reverse integration." "All we're doing is teaching religion … to whites, to Negroes, to anybody who comes. It's living the Gospel, plain and simple," he said at the time.

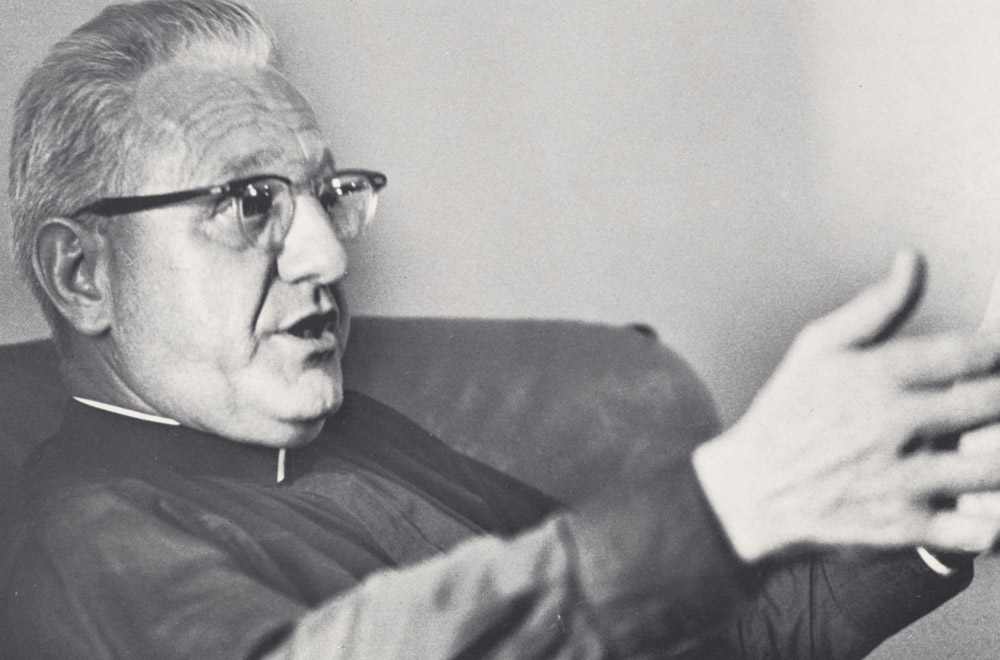

Fr. Mark Sterbenz (Courtesy of Salvatorian Archives)

News of St. Joseph's integration was overshadowed by the turmoil surrounding the desegregation of Huntsville's public schools. On the same day white students began classes at St. Joseph's, four African-American children were slated to become the first of their race to attend previously all-white public schools in other parts of the city. When they showed up at their designated schools, however, these youngsters found the doors locked. Alabama Gov. George Wallace had closed public schools scheduled for desegregation to prevent "disorder," although Huntsville school officials anticipated no anti-integration protests. Three days later, when the four black students returned, helmeted Alabama state troopers turned them away a second time. Not until Sept. 9, 1963, was the court-ordered desegregation accomplished.

Iconic images document the conflict-filled history of school desegregation in the Deep South. Fifteen-year-old Elizabeth Eckford hounded by a screaming white mob after being blocked from attending Little Rock's Central High School. Six-year-old Ruby Bridges protected by federal marshals on her first day of school in New Orleans. Wallace "standing in the schoolhouse door," trying to prevent two African-American students from entering the University of Alabama. Stories of peaceful integration are rarely heard. The voluntary desegregation of a previously all-black school is even more exceptional.

Students sing in class during the 1963-64 school year at St. Joseph's Catholic School, the first year white students attended the school. (Jack Hamilton/Courtesy of Salvatorian Archives)

Salvatorian priests founded St. Joseph's Mission in 1952 as part of their Negro Apostolate dedicated to bringing the Catholic faith to African-Americans. St. Joseph's School opened in 1956 with Salvatorian Srs. Ruth Dittman and Bernadette Kline teaching 61 African-American pupils in grades one through four. By 1963, the enrollment had doubled to 118 students in eight grades.

St. Joseph's School was launched during boom times in Huntsville. In December 1948, Redstone Arsenal, located on 4,000 acres outside of Huntsville, was designated as the center for the U.S. Army's rocket research and development program. Its workforce greatly expanded in 1950 when 1,000 additional employees arrived, including Wernher von Braun's team of German scientists. By 1954, more than 7,000 military and civilian personnel were employed at the arsenal.

Another growth spurt followed the 1960 opening of NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center. Thousands of educated young families flocked to Huntsville, attracted by the region's abundant job opportunities. The Huntsville school system struggled to keep pace with this influx, opening 21 buildings over a 15-year span. Despite these new facilities, schools remained crowded. Some children attended split sessions while others occupied portable classrooms.

Students at Holy Family School in 2017 (Courtesy of Holy Family School)

Peter and Isabelle Marrero were newcomers from New Orleans. Peter went to work for NASA after his Army discharge. Educated in Catholic schools, the Marreros wanted a religious education for their four children. Unable to enroll their oldest child, Mark, at St. Mary's School, they sought an alternative. A friend told them, "If you wouldn't mind the kids going to school with blacks, there's another Catholic school in town." The Marreros did not object. "We think that's a good thing," Isabelle replied. "We don't want them to grow up like we grew up." They joined St. Joseph's parish and registered Mark in first grade. Some white parents who sent their children to St. Joseph's School lost friends who disagreed with their values, a loss they were willing to bear. "Losing that sort of friend isn't so bad," said Mary DeMaoribus, whose child was among the first white students at St. Joseph's.

Both white and black parents appreciated the rigorous educational standards and emphasis on proper behavior imparted by the Salvatorian Sisters. Fourth-grader Maribeth Voltin, who transferred with her siblings from an all-white public school, insisted, "Here the kids are nicer and the teachers are nicer. My mother thinks this is the best school we've ever been in." Sonnie Hereford also transferred to St. Joseph's and noticed a difference right away. "My first impression at St. Joseph's was that it was harder than Fifth Avenue [School]," he explained. "I made straight A's at Fifth Avenue, but I made A's, B's, and C's at St. Joseph's with comparable effort."

Cheryl Davis Aruwajoye was a third grader when the first white children enrolled at St. Joseph's. She and other black students welcomed the new arrivals. "It was just more kids for us to play with and enjoy and get to know. Every time [a new student appeared] we'd say, 'What's your name? Who are you? Let's do this. Let's go do that.' "

For some white southerners, however, the sight of black and white children in school together could be unsettling. Aruwajoye recalled walking with her classmates to the Alabama Theatre to see "The Sound of Music."

"We had to walk hand in hand. There were black and white children mixed all throughout. People's heads turned like crazy — looking from their doors, looking from their homes, looking from their cars."

Group of students at Holy Family School in 2017 (Courtesy of Holy Family School)

Occasionally, St. Joseph's students encountered rejection when they ventured off campus. Stephanie Stimac, who taught fifth grade and was principal in 1968-69, recounted one instance when an integrated group of students was barred from skating at a local roller rink. The parish council handled the incident quietly, but decisively. Stimac recalled, "They went to the roller rink [management] and said, 'This is going to be a problem. You've got to accept them.' And after that they did."

St. Joseph's black and white students got along remarkably well considering the extent of residential segregation in Huntsville. The youngsters sometimes disagreed over minor issues, but their quarrels never had racial overtones. Mark Marrero recalled, "I had a great experience at St. Joseph's. We were just kids going to school." Cheryl Davis Aruwajoye enjoyed socializing with her white classmates. "After school there were times when we were at slumber parties and all races mixed together. When we went to the cafeteria we all would sit together. You mixed in. You didn't sit with all the white folks here, and all the black folks over there. That didn't happen."

Advertisement

St. Joseph's reputation for instilling respect and discipline spread quickly among white Catholics. By December 1963, the number of white pupils had increased to 25. Each year, more white parents sent their children to St. Joseph's, so many it soon was necessary to build additional classrooms. By 1968 the enrollment had doubled to 270 students — 182 were white and 88 were black.

With no Catholic high school in Huntsville, St. Joseph's graduates attended public secondary schools. Donna Tucker went to J.O. Johnson High School. She was "appalled and disheartened" by the racial climate she encountered there. "It was like [whites and blacks] hated each other," she said. After her first day at Johnson, she went home and cried. Donna's friend, Cheryl Davis Aruwajoye, went to S.R. Butler High School, where the athletic teams mascots were the Rebels and the school band played "Dixie." She remembered riots over displaying the Confederate flag at football games. "Getting caught up in that was really scary. You had to run for your life," she recalled. In the classroom she encountered "name calling and students that wanted to fight. I just wasn't used to that."

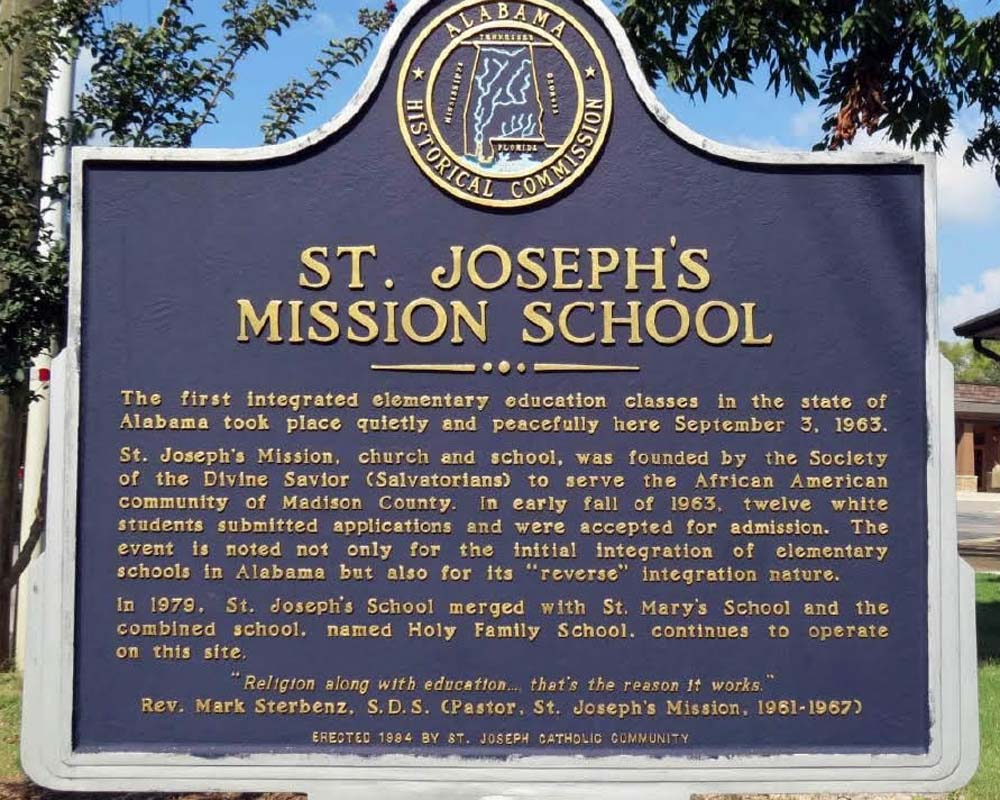

Historical marker in front of St. Joseph's Catholic School (Courtesy of Salvatorian Archives)

St. Joseph's alums stood out from their peers because of their friendships across racial lines. One white student told Stephanie Stimac if it hadn't been for his black friends from St. Joseph's, "I wouldn't have made it through the first year at Butler." St. Joseph's alumni also were better prepared academically. Cheryl Davis Aruwajoye recalled, "We were so prepared we could go and make straight A's just like that. No problem. It got so I didn't want to get A's because they would call me a nerd."

In 1979, due to declining enrollment, St. Mary's and Mary Queen of the Universe Schools merged with St. Joseph's; the new entity was renamed Holy Family School.

On Aug. 6, a diverse student body of 266 young people reported for their first day of classes. A historical marker in front of the school reminds students and visitors of St. Joseph's "first in Alabama" status. Its text concludes with a quote from Fr. Sterbenz: "Religion along with education. … That's the reason it works."

[Paul Murray is professor of sociology emeritus at Siena College in Loudonville, New York. His research focuses on Catholic activists in the civil rights movement. He encourages alumni of St. Joseph's School go contact him at murray@siena.edu.]