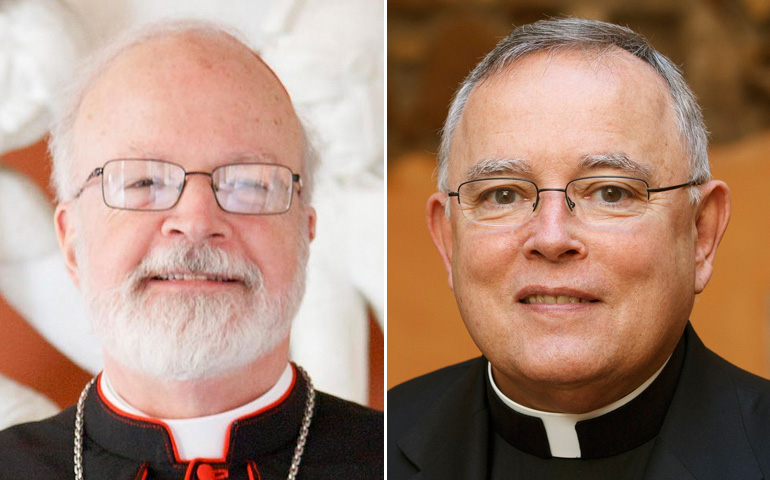

Cardinal Sean O'Malley of Boston and Archbishop Charles Chaput of Philadelphia (CNS photos)

As someone who grew up amid two sprawling extended families with battalions of cousins, many of whom lived in the same town and attended the same Catholic schools, I know how unfair it can feel to be compared with someone just because you're members of the same tribe.

That notation is a way of expressing some understanding should Cardinal Sean O'Malley and Archbishop Charles Chaput grow weary of being compared. The two are both Capuchin Franciscans, were once classmates, and are currently, as colleague John L. Allen Jr. described them in a recent column, "ecclesiastical heavyweights." Each heads a historic U.S. see: Chaput is archbishop of Philadelphia and O'Malley is the archbishop of Boston, tapped by Pope Francis to be one of eight cardinals on a committee to help him in reform of the Curia and governance of the universal church. They also were both recently speakers at a gathering of Capuchins outside of Pittsburgh, and what they had to say was as revealing as any seminar one might attend on the different approaches to being a Catholic pastor in the 21st century. It's not the first time the glaring contrasts between the two were apparent.

A year or so ago, I was asked to do a chapter in SAGE Publications' Religious Leadership: A Reference Handbook. I began with a comparison of Chaput and O'Malley, citing the by-now familiar similarities before describing the dramatically different ways they pastorally approached a similar circumstance in 2010.

The problem arose when children of homosexual couples showed up for admission to a Catholic school. The first incident involved two girls, ages 5 and 3, in Boulder, Colo., part of the Denver archdiocese, where Chaput was archbishop at the time. The pastor involved said the girls couldn't be accepted because of their parents' sexual orientation, explaining at one point that "Jesus did turn people away." Chaput supported the pastor, citing the need to uphold "the authentic faith of the church." He later further approved the decision, noting in his blog, "Archdiocesan policy was followed faithfully in this matter." The situation, he said, illustrated the importance of Catholic teaching and its preservation. The teachings were, in fact, "the teachings of Jesus Christ," he said.

Two months later, a pastor denied an 8-year-old boy admittance to a school in Boston for the same reason -- he had homosexual parents. O'Malley quickly reversed the pastor's decision, and the school's superintendent released a statement saying while the church's teachings are important, no child would be sent away.

O'Malley on his blog explained his decision by telling a story of his experience as a young bishop in the West Indies. A notorious madam who ran a local brothel was murdered, and O'Malley said her funeral Mass. "At the Mass I met the woman's daughter, a lovely little girl. I asked her what grade she was in. She replied that she didn't go to school. I sent a stern glance to her grandmother, who said: 'Her name is the same as that of the brothel. The other children were so cruel to her, she left the public school.' I told her grandmother, 'Take her to the Catholic school tomorrow.' "

He further said Catholic schools "exist for the good of the children. ... We have never had categories of people who were excluded."

On the margins

Perhaps the comparison is unfair. But both prelates are big boys who have either been thrust into the public limelight (O'Malley has several times been parachuted into dioceses reeling from the sex abuse scandal) or sought it (Chaput, who also was given an unenviable assignment in Philadelphia, has taken on the role of spokesman for a certain conservative wing of the church).

During the May 28 Pittsburgh gathering, O'Malley recalled the enthusiasm Italians showed for Franciscans during the recent papal conclave in Rome and said he had told other Franciscans, "We have to make sure we deserve that affection." In other words, position, office, order don't automatically make one deserving of the affection and goodwill of others.

His emphasis throughout his life has been on the poor and those on the margins, and he recalled sheltering people in the wake of riots that broke out in Washington, where he was then living, following the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968. O'Malley followed that by joining the Poor People's March, "sleeping in a tent city" and watching protestors get tear-gassed.

He was a prison chaplain and ministered to immigrants and refugees while staying at Washington's Centro Catolico Hispano during the 1970s and '80s. He got to know, close-up and personally, the reality of immigrants, their struggles and life with "no heat, no hot water, and rats the size of cats." He organized a rent strike among poor tenants until improvements were made to their property.

He spoke warmly of Pope Francis, his emphasis on Catholic social teaching, his wish for "a poor church for the poor" and realistically about the need for a mechanism to hold bishops accountable.

Chaput focused on, in Allen's construction, "the integrity of the faith in a very secular culture."

That's a polite company way of putting things. Chaput's is a rather gloomy view of the church and the world. Inside the institution, he is gloomy over the drop in numbers -- of Catholics, of those getting married, of the number of Catholic schools closing. "In much of the once-Christian developed world, many self-described Christians are, in fact, pagans," he said. His language is littered with phrases that are derisive of everyone else. "Practical atheism" has replaced Orthodoxy and the creed of American teenagers is one of "moralistic and therapeutic deism."

Everything is "in worse shape now that I would ever have imagined even 10 years ago, as a society and as a church." Evil is "real," "murderous," "all around us." We are in a cosmic "struggle for the soul of the world."

When asked if he sees even a little hope, he replied, "I see some lights, but they're not many and they're small."

Above the fray

Everything, it seems, is someone else's fault, and Chaput appears to hover above the fray, with both the accusatory analysis and all the answers. Not once did he even hint that perhaps Catholics in places like Philadelphia were leaving in droves because church leaders, especially bishops, deeply and horribly betrayed them in ways that would put the most relativistic, hedonistic secularist to shame. Perhaps they were leaving because they can't stand to be in an institution led by men who had so little regard for their children that they would tolerate the rape and molestation of those children for decades without saying anything to anyone.

Chaput at one point said he'd "love to see some of these communities [churches that are being closed] say we have to start over, setting up shop in the storefronts rather than these huge churches we can't maintain anymore. But nobody does that."

Did he stop for a moment to reflect on what has happened to Catholics who dare try something experimental? Does he know what happened, for instance, to a community in Cleveland that did what he is suggesting? The Community of St. Peter set up shop with their pastor in an industrial warehouse when the bishop closed the church. The bishop excommunicated the pastor and told the community it wasn't in communion with the church. Perhaps Chaput would tolerate such experiments, but he doesn't have a reputation for embracing innovation.

He wants to see a revival of secular Franciscan communities. However, of those who have remained in such communities, he had this to say: Too often, they are composed of "old people or left-leaning social justice folks from the 1960s."

Not even his own order escaped his critique for not joining in the renewal effort of Fr. Benedict Groeschel, who broke with the Capuchins in 1987 to found the Franciscan Friars of the Renewal. Groeschel has since retired from all of his posts following some rather bizarre comments he made about the sex abuse scandal. But even when it comes to Groeschel's renewal effort, Chaput remains above it all, excusing himself from the fight (if not the critique) because he had just been appointed a bishop in 1988 and was busy then with whatever new bishops do.

The contrasts in the two prelates are apparent and have to do with personality as well as ecclesiology and theology. Over the long haul of history, the church perhaps needs all types of leaders, including the exceedingly pessimistic. But given the realities of the current era and the fact that most bishops would line up behind one model or the other, it is fair to ask: Who would you prefer to follow? What kind of church would most people be inclined to enter? What kind of community would most of us prefer to join?

Is it the one led by the cardinal whose principal texts seem to be Scripture and his life? Or is it the one led by the archbishop who seems to lean heavily on a neoconservative understanding of history, memorized catechism answers, and an endlessly gloomy critique?

Are we more likely to be attracted to the invitation into a life, a story if you will, of transformative love, rats and all, or one in which the criticism of our lives, beliefs, efforts and culture is relentless and without much hope?

One hopes it is not without consequence that during the same week Chaput was delivering his sermon of doom and condemnation, the pope spoke about "becoming slaves to our sorrows." Reflecting on the day's readings, Francis said, according to a Vatican summary, "It all speaks of joy, the joy that is celebration." Yet, "we Christians are not so accustomed to speak of joy, of happiness. I think often we prefer to complain. ... Without joy, we Christians cannot become free, we become slaves to our sorrows. The great Paul VI said that you cannot advance the Gospel with sad, hopeless, discouraged Christians. You cannot."

The critique, of course, is essential. It has always been an element of Christian life. But at some point, the more difficult task of leadership has to surface. The community must be invited into the larger story. It has to be inspired to live something more, to be transformative, or it withers away. It has to have reason to place its faith and hope in something other than sarcasm and a bitter list of complaints.

[Tom Roberts is NCR editor at large. His email address is troberts@ncronline.org.]