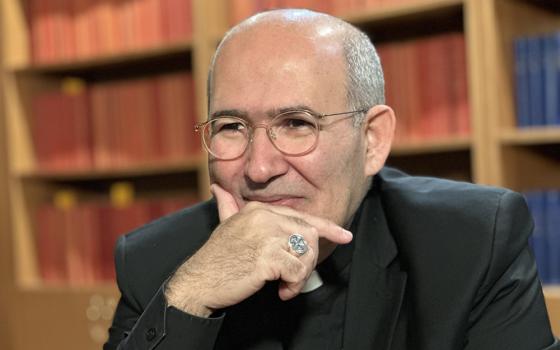

Detail of "Evil" by Ed Ruscha, screenprint on wood veneer, 1973, 19 7/8" x 30 1/8", featured in "Ed Ruscha: OKLA," running Feb. 18 to July 5, 2021 at Oklahoma Contemporary (Courtesy of the artist and Gagosian)

If Ed Ruscha's name is unfamiliar, you're in extensive company. Since 2015, Google searches for obsolete mimeographs have outpaced those for the Catholic-born octogenarian, whom museums practically venerate, from the London Tate to Los Angeles' Broad. For those who extol price tags, a 1964 Ruscha oil painting sold in Nov. 2019 for nearly $52.5 million.

If you've reached the Museum of Modern Art's 404 error page, you've seen Ruscha's "OOF" (1962) — blocky, yellow letters against a deep blue field. Everyone understands the word "oof," though it's nonsensical, according to independent scholar and curator Alexandra Schwartz, who finds the work amusing. "It sums up how he takes verbal language and turns it into something visual in a way that you don't expect," she said.

Advertisement

The unexpected emerges also in the Oklahoma Contemporary show Schwartz co-curated, "Ed Ruscha: OKLA" (running Feb. 18 to July 5, 2021), Ruscha's first solo exhibit in the state where he grew up. Most exhibits about Ruscha ("roo-SHAY") center on his adopted home, since 1956, of Los Angeles, so mining Oklahoma's impact on him is rarer. Exceptions include the University of Oklahoma Fred Jones Jr. Museum of Art's "OK/LA" (through March 7, 2021), and "Out of Oklahoma: Contemporary Artists from Ruscha to Andoe" (2007-08) at the Fred Jones Jr. Museum of Art and the Bartlesville, Oklahoma-based Price Tower Arts Center, within the only skyscraper Frank Lloyd Wright made.

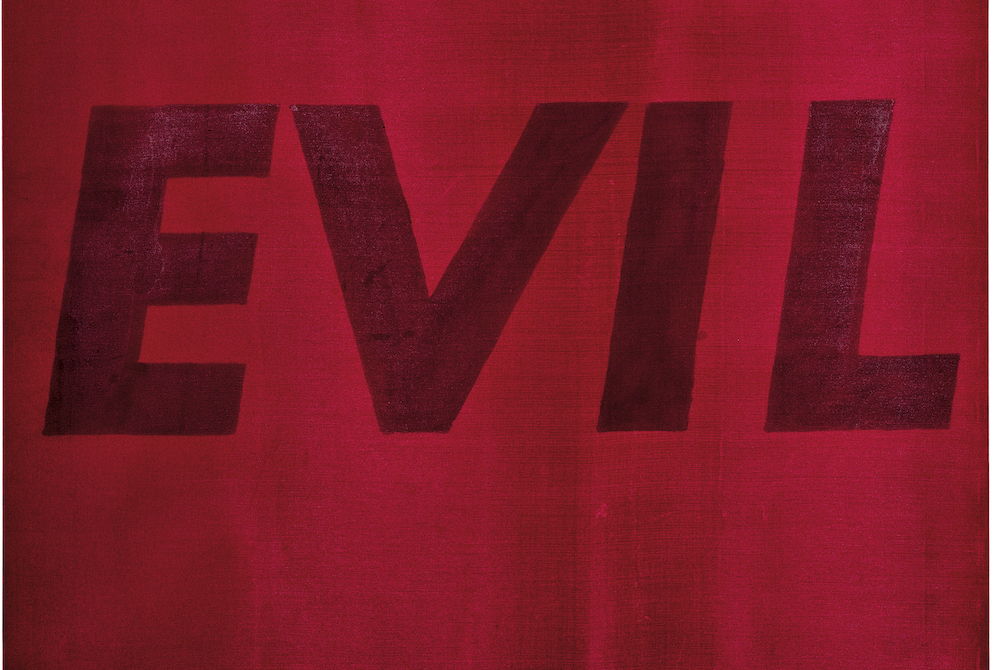

Even less common, Oklahoma Contemporary addresses Ruscha's Catholicism. Of 70 exhibited works, 10 appear in a section named for one of them, "51% Angel, 49% Devil" (1984). The others are: "Amen" (2008-09), "Angel" (2006), "Evil" (1973), "Heaven" (1988), "Hell" (1988), "Miracle" (1999), two works titled "Sin" (1970, 2002) and "The Holy Bible" (2003).

Catholic ceremony and visual icons have affected him subtly and appear occasionally in his work, but there are no direct references to the Catholic Church, according to responses the museum provided from Ruscha. "I am a confirmed atheist today, but the church helped me get where I am."

But Schwartz and Jeremiah Matthew Davis, Oklahoma Contemporary's artistic director, think the Catholicism of Ruscha's youth continues to impact his life and work. "You can still see the elements of that religion informing his day-to-day thinking whether or not he describes himself as a practicing Catholic," Davis said. "Catholicism is still with him."

"Sin" by Ed Ruscha, screen print on paper, 1970, 19" x 26 1/2" (UBS Art Collection/Courtesy of the artist and Gagosian)

The author of two Ruscha books, Leave Any Information at the Signal: Writings, Interviews, Bits, Pages (2002) and Ed Ruscha's Los Angeles (2010), Schwartz thinks Catholicism was an important part of his artistic development. "I think it's clear through his work that he thinks about good and evil, and what is the nature of goodness," she said. In his Miami-Dade Public Library rotunda design, Ruscha features the "Hamlet" quote, "Words without thoughts never to heaven go." This reflects his love of books but also, to Schwartz, how deeply spirituality infuses his oeuvre.

Other works, including a short film, address miracles. Rays of light in the Getty's wall-sized "Picture Without Words" (1997) echo "Miracle" (1975). Schwartz recalls Ruscha discussing Renaissance altarpieces as inspiration. "It seems to me that he's making a connection between that kind of religious painting and the size and scale of an altarpiece in a Venetian church with that of the painting at the Getty," she said.

Schwartz also thinks Ruscha's Catholic upbringing played a role in his recent painting of a tattered American flag, "Our Flag" (2017), which the Brooklyn Museum displayed while serving as a polling station. Ruscha had long avoided political statements, but he came to see "this very dark turn in American life" as "some kind of battle between good and evil," Schwartz believes.

"There's something that seems quite embedded in his early life and Catholic upbringing, thinking, and the observations and critiques he makes," she said. "He felt the need to make political statements, because he sees it as so dire, or he did."

Left: "Heaven" by Ed Ruscha, edition 5/25, soap ground aquatint, 1988, 54” x 40 3/8"; Right: "Hell" by Ed Ruscha, edition 5/25, soap ground aquatint, 1988, 54" x 40 7/16" (Courtesy of Ed Ruscha Studio)

"After the 2016 election, all I could see was black skies and vulgarity ahead of us," Ruscha wrote to NCR in December. "I could see the tyranny of fascism coming. Now we have a shred of hope to look forward to in 2021."

Schwartz recalls Ruscha really wanting to include a photo of himself at his first Communion on April 8, 1945, in her book. "There's got to be a reason for that," she said. In a Smithsonian Archives of American Art oral history, Ruscha noted he couldn't be an altar boy or join the Holy Name Society, since his dad was divorced. The latter never missed Mass but didn't take Communion.

"I liked the ritual; I liked the incense. I liked the priest's vestments … there was a deep mysterious thing that affected me," Ruscha said in the oral history. "Then I learned more about the church, and it became more hypocritical, to the point where I just had to say 'adios.' "

The complicated contours of Ruscha's Catholic identity as a boy overlap with his Oklahoma upbringing. Since moving to the West Coast with a group of Oklahoma friends, he continues to visit his home state of 65 years ago, often more than annually, Davis said. Oklahoma remains a significant part of his art, too.

Davis said that Oklahomans will "recognize the colloquial and vernacular connections to the state immediately and will understand them in a way that perhaps some art audiences in more cosmopolitan or established contemporary art markets might not," he said. "They may not see the same valence."

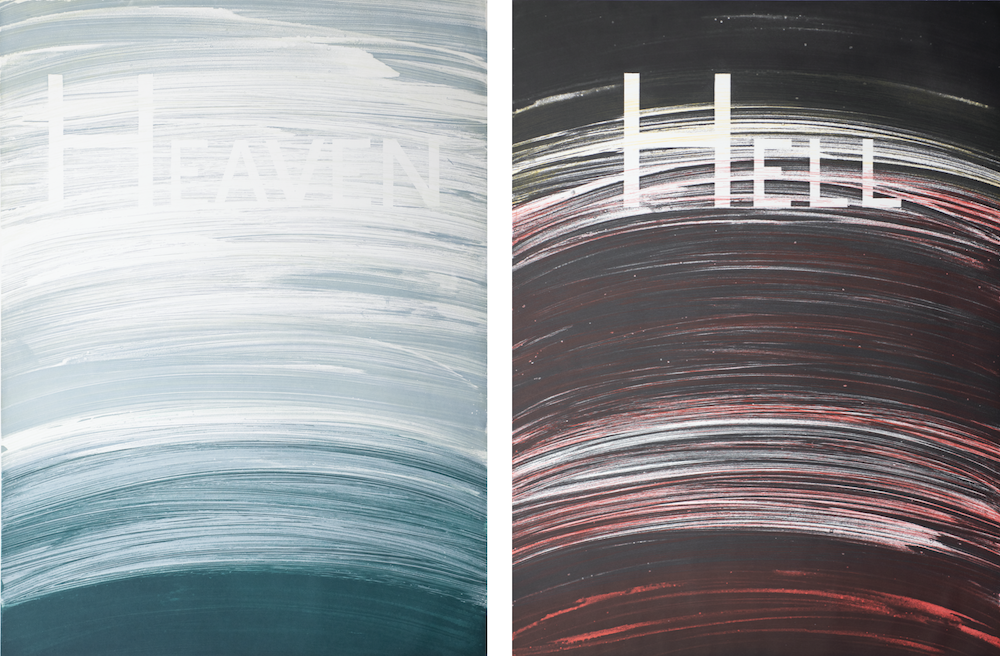

"Figure It On Out" by Ed Ruscha, acrylic on canvas, 2007, 60" x 60" (Courtesy of Ed Ruscha Studio)

The preposition "on" in "Figure It On Out" (2007) may trip up out-of-towners, as may double (and triple) negatives, as in "I ain't telling you no lie" and "I never done nobody no harm." Ruscha's "Well Well" (1979) shows oil derricks — or wait for it, wells — on either end. They are immediately identifiable to those who live in a state where oil is such a part of the economy and mythology.

"The idea that a good batch of my artwork will be in one of the inaugural exhibits at the Oklahoma Contemporary is truly fulfilling. You take the boy out of Oklahoma, but the boy comes back," Ruscha wrote to NCR. "One detail that I miss on returning are the Osage orange trees that once lined Western Avenue all the way to Guthrie. I miss the black and white dust bowl vision of Oklahoma with mom and pop cafes that no longer exist. But I see hope when I drive out to the Panhandle."

Chicago-based career museum director and curator Richard Townsend wrote of Ruscha's Oklahoma ties in the 2007-08 exhibit he curated at the University of Oklahoma museum and Price Tower Arts Center.

"Ed Ruscha admitted from his Los Angeles studio, 'Oklahoma is a million miles away but it's right in my face,' " Townsend wrote in the 2007 catalog. Asked what an Oklahoman may mean by taking the boy out of state without taking Oklahoma out of the boy, Townsend, who grew up in southeastern Kansas a couple of hundred miles north of Oklahoma, said the latter embodies "a contradiction of limitless opportunity with limited world view, money, sophistication, and aspiration with a narrowness and history of oppression," as in appropriation of Indian territory. (Townsend has Osage Nation heritage.)

Townsend hadn't known that Ruscha was Roman Catholic and is glad that aspect of the latter's life is being studied. He sees spirituality in Ruscha's art. "Whether you're looking at the galleons on the sea or a flat horizon line or a turbulent sky or an alpine mountain, it's wondrous. And that's spiritual," Townsend said.

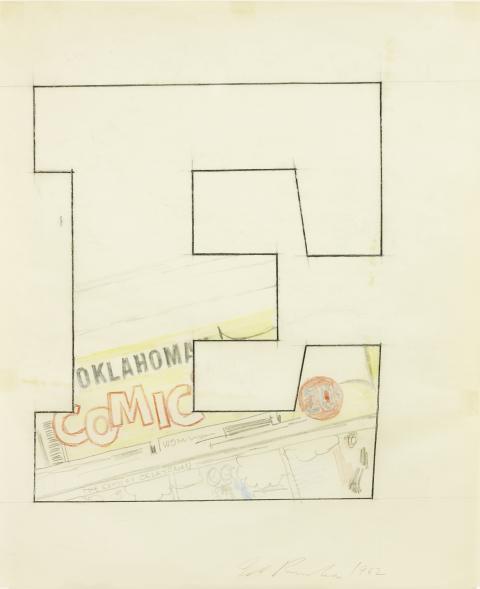

"Oklahoma E" by Ed Ruscha, pencil, colored pencil, charcoal on tracing paper, 1962, 17” x 14" (UBS Art Collection/Courtesy of the artist and Gagosian)

But Townsend thinks that viewers who read Catholic references into Ruscha's works in one gallery of the Oklahoma Contemporary show will find, in other rooms, different words, often secular, set against the same backgrounds.

"The religious dimension is there if you wish," Townsend said. "When he says 'Amen,' it's like 'Unit.' It's very tempting to say, 'Ah.' But let's look at this with eyes wide open. They're just words. But that spiritual sense that comes through in the wonderment of these blasted landscapes and low horizons and his use of city lights that go on forever, they are religious. Or I should say, they are spiritual."

To Davis, the new exhibit can demonstrate to those who think contemporary art is constitutionally opposed to religion that the two needn't be mutually-antithetical. "I would love for us to put to bed the false narrative that somehow contemporary religion and contemporary art can't reconcile, or are inherently diametrically opposed," he said.